So far, I’m not quite old enough to entertain any worries about the youth of the nation or the deficiencies of their character. Plenty of today’s young adults actually strike me as irritatingly great: Growing up with the Internet means they knew by age 10 what I learned last week, and a lot of them seem awfully bold and brave about asserting themselves all over everyone.

My opinion might be in the minority. Lately, the conventional wisdom is that young people think far too much of themselves—they’re coddled little zeppelins of ego in desperate need of shooting down. The cover of July’s Atlantic is emblazoned with the headline how THE CULT OF SELF-ESTEEM IS RUINING OUR KIDS; inside, quotes from psychologist Jean M. Twenge explain how we’re producing generations of feckless narcissists. Earlier this year, the online equivalent of applause greeted a study of pop lyrics from 1980 to 2007 in which a whole team of psychologists, Twenge included, claimed there’s been a rise in narcissism, self-regard, and antisocial hostility at the top of the Billboard charts: Songs have moved from we and us to me and I, and come over all ornery in the process. Surprised? New York Times columnist David Brooks, for one, already saw that as self-evident: “It’s nice,” he wrote, “to have somebody rigorously confirm an impression many of us have formed.”

“Rigorously” is a stretch. The study consists of little more than running ten lyrics per year through a word-counting computer program, which I can’t imagine taking longer than an afternoon. The study’s authors aren’t much interested in music, either: They’re merely using it as collateral evidence of some decades-long cultural slide into self-absorption. Books to their names include The Narcissism Epidemic and Generation Me: Why Today’s Young Americans Are More Confident, Assertive, Entitled—and More Miserable Than Ever Before. As that subtitle suggests, these academics fret about a tidal wave of narcissism because they’re convinced it’s bad for the narcissists, leaving them ill-equipped to deal with the world. “They come off as confident,” the study’s co-author, C. Nathan DeWall, told NPR, “but if you insult or provoke them in any way, it sort of breaks their bubble, and they’re very fragile people.” That same week, bubble enthusiast Lady Gaga—who once said, “I want people to walk around delusional about how great they can be”—burst into tears when a journalist asked her about her recent single’s resemblance to a Madonna song.

Most of narcissism’s critics, however, do not evince much concern for its sufferers, whom they regard with more Schadenfreude than pity. They just find all this expression of ego to be grating, gauche, and borderline immoral—like wearing tights as pants, talking during movies, or being Snooki. This is our new cultural mini-monster, somewhere down the scale from terrorists and pedophiles, in the general vicinity of Charlie Sheen and those people who go nuts during American Idol auditions: the Raging Narcissist. Press coverage of that music study conveys the sense that a song like Keri Hilson’s “Pretty Girl Rock”—whose refrain runs, “Don’t hate me cause I’m beautiful”—is a substantial threat to the nation’s soul.

The results of the study were announced at a funny moment: right amid a string of hit singles about self-esteem, all operating on the premise that the listener could stand to have more of it. Katy Perry’s “Firework” reassures you that “you don’t have to feel like a waste of space” and exhorts you to “show them what you’re worth.” Pink commands: “Don’t you ever ever feel like you’re less than fuckin’ perfect.” Lady Gaga, Warholian per usual: “We are all born superstars.” Ke$ha: “We’re superstars / We are who we are.”

How you feel about those sentiments probably depends on a few things (including whether you’re the type of person who considers pop music vapid on its face), but it’ll surely end with whom you imagine listening to the songs: the vulnerable souls they’re addressed to, (1) or the preening egotists currently terrifying research psychologists.1. These songs hit the charts just after Dan Savage’s “It Gets Better” campaign, reaching out to distraught LGBT teenagers, begins on September 21, 2010.

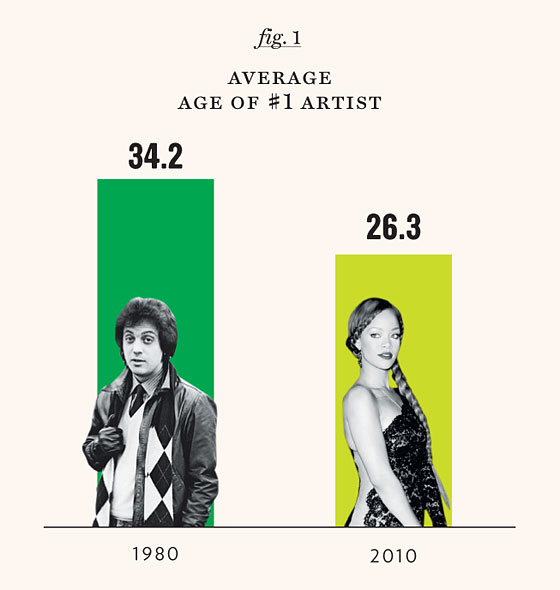

And if you want to talk about pop music between 1980 and now, that issue—the question of who’s singing and who’s being sung to—is an important one. The study assumes that hit singles in the eighties and hit singles in the new millennium play the same role in our culture. But over the past 30 years, the weekly charts have seen changes a lot more significant than any surge of ego. It’s not just that pop’s audience has changed; it’s that its whole purpose has.

Here, for instance, is a chilling fact about the nineties: In any given week of the decade, there was a 10 percent chance the No.1 song was by Boyz II Men. Add Whitney Houston, Mariah Carey, and Bryan Adams, and chances hit 24 percent. Americans spent a quarter of a decade listening to this sort of thing: big, lavish ballads, built to charm middle-aged and middle-school listeners alike. Try to picture an environment or purpose for these songs, and the mind drifts to graduations, school-gym talent shows, Olympics montages.

In the aughts, there was still a one-in- four chance that any given week’s chart-topper came from one of four artists. But those artists were Usher, Beyoncé, the Black Eyed Peas, and Nelly, and their hits were pointed at a very different kind of public environment: They were club songs. The old-school, all-ages ballad spent much of the decade reduced to a tiny corner of the charts, populated by nice-guy crooners like James “You’re Beautiful” Blunt and Daniel “You Had a Bad Day” Powter.

One simple explanation for this development: We now have access to a ridiculous variety of media. The music we spend our private time on, and use to build our identities, varies more wildly than ever from person to person. But there’s at least one kind of music that needs consensus to function, and that’s the stuff we dance, party, and strut around to. “The club” might be the last remaining space where strangers are all forced to pay attention to the same songs. And whether it’s an actual club or just a bedroom, it tends to be a space where people enjoy feeling fabulous.

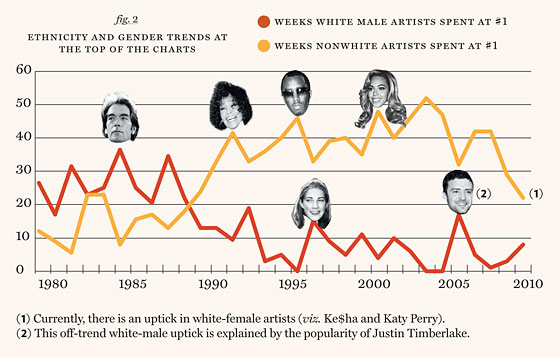

Another change that’s swept through the charts since 1980 is the steady disappearance of white men. In 1980, more than half the artists at No. 1 were white men; in 2010, the only white guy in the top spot was Eminem. Today’s pop world is female, African-American, and Latino, dance-pop and hip-hop and R&B. The audiences it’s usually associated with are female, African-American, Latin, gay, and young. And the music running through the charts is filled with qualities that look a lot like the aspirations and survival strategies of people who’ve felt marginalized—people for whom ego and self-worth can be existential issues, not just matters of etiquette.

This isn’t some arcane sociological observation; empowerment is a selling point of the music itself. It’s almost redundant to explain how hip-hop has schooled the nation in some of the tools and postures of an underclass, from persona-building to competitive braggadocio as a form of entertainment. (Even something as basic as the way rappers used to move their arms is now part of the physical vocabulary of most Americans under 40.) (2) Today’s dance music still carries traces of gay club culture—spaces where people could perform gender and sexuality in ways they couldn’t elsewhere. Just about every young woman on the charts is navigating a complicated matrix of beauty standards, sexual roles, power dynamics, and good-girl/bad-girl dichotomies. Questions of self and self-esteem are unavoidable.2. January 24, 2004: Jay-Z releases the single “Dirt Off Your Shoulder.” April 17, 2008: Senator Obama addresses campaign attacks using the “brushing dirt off your shoulder” gesture.

This is as far as you can get from the early eighties, when the charts still reflected the tastes of grown, upwardly mobile baby-boomers—probably the least marginalized cohort in recent American history. In 1980, nearly half of our No. 1’s came from artists who had their first hits in the sixties; for a few years after, much on the charts seemed aimed at people on the verge of a boat purchase or signing up for adult education. (3)

Since then, genres like rock have sunk further and further beneath the notice of the pop charts. Same goes for a lot of the music you might associate with middle-class boys—and the particular forms of ego and hostility that sometimes come with them. The occasional hair-metal ballad hit big in the eighties, but all those Poison and Mötley Crüe songs about hedonism and Satan made less of a mark. The antisocial grumbling of nineties alt-rock never climbed very high (a single from Color Me Badd was nearly twice as likely to chart as one from Nirvana); neither did the boyish rage of nu-metal or the grandiose self-pity of emo. Same goes for the cocky individualism of serious rap (as opposed to its party hits).

The bulk of this music will never get played on the radio or attract the paternalistic tsk-tsking of mainstream observers, but it isn’t necessarily any less “narcissistic” than the songs on the pop charts—some genres are self-deprecating, others polite but navel-gazing, others pathologically ego-driven. The songs get to seem like they’re venting to their own audiences or abstractly spilling someone’s thoughts instead of preening or seeking attention in the real world. Our day-to-day moral scolding is attached to the songs we hear too often in stores or imagine warping the sexuality of impressionable teenage girls (rarely boys); meanwhile, a massive and ever-growing share of the music people actually listen to broods in private, being as antisocial as it wants.

Pop, however, remains stubbornly public and resistant to impressionistic thought-spilling—right now, it feels like the music that’s most explicitly committed to real-world social matters. Hit club tracks are built for dancing and courtship; R&B and country singles catalogue, in precise and unflinching detail, every last swoon, sob, and smashed-up car window that results from people, narcissists or not, getting involved. Scan down the Hot 100, and the songs talk with increasing frankness about ego, beauty, money, cheating, posturing, partying, and every other element of solid gossip.

You could complain about what these songs actually have to say on such topics: They can be superficial, misogynist, and downright stupid. You see female sexuality presented as a performance for men. You see self-aggrandizing persecution complexes, like Chris Brown’s. The problem with that “Pretty Girl Rock” song isn’t that it’s about feeling hot; it’s the suggestion that being hotter than other women is a good way to feel better about yourself.3. Role played by Lionel Richie in the video for 1984’s “Hello”: Art professor. Where Rick Springfield met the woman who inspired “Jessie’s Girl”: A stained-glass class.

But why sweat the preening itself? The prevailing attitude—that all this self-love is unseemly and vapid—seems almost mean-spirited, especially given what non-pop musicians get away with. If we can defend rock lyrics about violence on the grounds that music is a safe space to talk about antisocial feelings, shouldn’t pop be a safe space to talk through odd ideas about, say, ego or beauty? Richard Russell, the head of XL Recordings, recently told the Daily Mail that the “faux-porn” images in pop videos made him feel “queasy”—but he said this just weeks after releasing a record on which a young man tries to needle listeners by rapping about rape. You get the sense that people find it more horrifying—or less artistic—for young women to toy with sex and self-image than for young men to toy with actual violence and hostility. But if either of those things is more vapid and distasteful than the other, there’s a good chance it’s the latter, right?

At 33, I’m just a few years older than the oldest of what we’re now calling Millennials. Which is to say I was born just in time to inherit the wry disdain, detachment, and self-deprecation of Generation X, then watch it immediately expire and lose value. If I could choose, in retrospect, which set of music-based pathologies to spend my teenage years absorbing—the dogged outsider mumbling I picked up from indie-rock records or the brave thrusting entitlement and self-regard that allegedly speak through today’s pop—there’s a decent chance I’d take the pop. Sure, it feels gauche to say that; the path of modesty and self-sacrifice must be more noble, right? But there’s also an embarrassed, self-effacing quality there that’s hard to recommend. Besides, if those psychologists are correct, and our culture is increasingly deluged with narcissism and entitlement, we might really need pop’s poses and costumes to help us navigate it—to have songs that feel out the dimensions of every last way to think you’re hot shit.