Early on the morning of January 3, 2005, back in New York after visiting family in Ohio, Aaron Lazar and his girlfriend drove over the Manhattan Bridge, made a right on Canal Street, and stopped at a red light. It’s the last image Lazar remembers.

Four years later, he tries to describe the sensation that followed. “You know when you take your first hit off a cigarette?” Lazar asks. “That nicotine sick you get, that nauseous, swimmy, gross feeling? It was like that—only with a tunnel vision that kept going and going and going.”

Lazar slumped over the wheel. His girlfriend nudged him, called his name, then started screaming. An ambulance happened to be nearby, and paramedics saved his life with a defibrillator. Lazar was rushed to Beth Israel hospital, in time for him to become one of the less than 5 percent of people to survive a syndrome known as sudden cardiac death. He was 27 years old.

The diagnosis describes “an abrupt loss of heart function,” per the American Heart Association, in which “the time and mode of death are unexpected.” Stunned friends and family assembled at the hospital, where they found Lazar unconscious but stable. Then his heart stopped again. Eventually, a doctor came into the waiting room with an update. “She had that look like she’d been crying,” says his friend Damien Paris. “And she was like, ‘Chances are he’s not gonna make it through the night.’”

But a day later, Lazar regained consciousness. “I’m like, ‘There’s a tube in my dick, there’s a tube in my throat, there’s tubes in my arms—what the fuck?’” The doctors told him he had died twice. For days, they searched for a cause—inserted cameras, injected dyes, discussed electrocuting him while he was conscious. Finally, a cardiologist looking over his charts discerned an irregularity in his heartbeat and they agreed on a solution: an ICD, or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, a battery-powered device that would be permanently installed in his chest to sense his cardiac rhythms and, if necessary, administer a lifesaving shock.

Doctors performed the implantation the next day, and Lazar soon left the hospital, a miraculous survivor of a deadly condition—and, needless to say, someone well advised to avoid overstimulation. Actually, more than advised: If his pulse rate were to rise above a certain level, the machine in his chest would deliver 750 volts to his heart. He could exercise, within reason, and he needed to steer clear of magnets and certain electronics that might interfere with the device. But he was free to pursue a full life as one of over half a million Americans living with an ICD. A full life, but not necessarily the life of a stage-diving lead singer of a punk-metal band.

For years, the Giraffes were known as one of the most dangerous bands in the city. They sang about soccer riots, baited audiences, threw bottles, and even managed to get themselves shot. Guitarist Paris—who still carries a slug in his tibia from a 2003 clash with a fire marshal—formed the group in 1996 with drummer Andrew Totolos, a shaven-headed commercial actor whose roles tend toward psychos and neo-Nazis. Paris handled vocal duties for a few years before bowing to suggestions that they get a singer. Someone mentioned a die-hard Giraffes fan named Aaron Lazar.

A tall, darkly handsome grad student in NYU’s art program, Lazar had grown up in crack-ravaged Youngstown, Ohio, the son of a Vietnam-vet shop teacher and an academic. In 2000, Paris was given a tape of Lazar singing Prince’s “The Beautiful Ones” in a sublime, intoxicated falsetto. “He sang it all drunk off his ass,” Paris says. The band had a lead singer.

Over the next four years, the Giraffes recorded three albums of dense, gnarly rock, much of it written by Lazar, in the vein of early-eighties hard-core bands like Black Flag and Bad Brains, trading in the standard sick jokes and morbid fantasies of white-boy ironists. By 2005, they had a national underground following. Then came sudden cardiac death.

A few weeks after leaving the hospital, Lazar, shaky and depleted, returned to performing. He was tentative for a couple of shows, singing stock still, dodging any physical involvement. But before long, muscle memory took over. “By the third or fourth show, he’s kicking me in the pants, shoving me, throwing shit at me,” says Paris. “And I was like, ‘All right!’” A fully reconstituted mosh engine, they continued rocking and raging just as before. Then came round two.

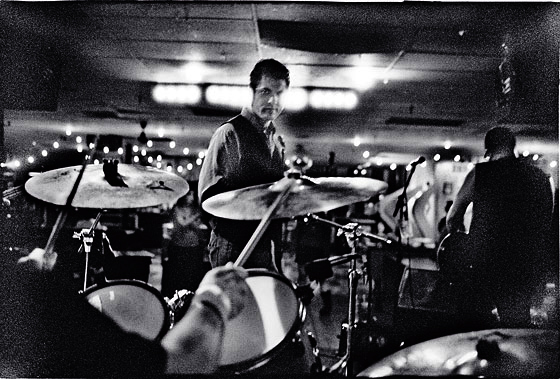

On March 29, 2005—just about three months after the first attack—the Giraffes were playing a sold-out Chicago show. “We were rockin’, we were doing well,” says Totolos. Lazar “was windmilling a mike stand, jumping around, falling on the floor.” The band kept stoking this aggro bacchanalia right into the second-to-last song, “Sugarbomb.” Totolos got the tempo going to around 192 beats per minute. “I was hitting each one with the snare and [Lazar] was matching each hit—going ‘Hey! Hey! Hey! Hey!’ on every single one,” he says. The song ended with the standard late-set mayhem, with Lazar falling on his back and pulling Paris down on top of him.

But then he sensed a force of an altogether different magnitude. “I heard that weird sound you get when a camera’s flash is charging—that rising electronic whine,” Paris says. “I thought, That’s not good. And then—boom!” Paris and Totolo describe a spectacle similar to a rider bucked by a bull at a rodeo. When he came to—ears ringing, chest pounding—Lazar made a throat-cutting motion. Paris took this as a cue to start the next song. “I thought he was wildin’ out,” says Paris. “I’m like, ‘Yeah! Rock on!’ And then—boom!” The second shock hit, flinging Lazar again.

After the third shock in 30 seconds, he struggled to a crouch. He began taking his pulse, trying to calm himself, then made his way to the wings. Finally Totolos took the mike: “I said, ‘Well, uh, our singer’s gonna die, so I guess…’ But before I could finish my sentence, he comes running back out and says [in a hoarse yell] ‘Finish it!’”

Afterward, Lazar walked out of the club and hailed a cab to the hospital. Technicians accessed the automatic history of the defibrillator, pinpointing the precise moment of near-fatal activity: when his heart rate hit 192 beats per minute, the tempo of the song “Sugarbomb.”

Lazar returned to New York and met with his doctors and a rep from the ICD manufacturer. One doctor confronted him directly. “She said, ‘You really should not be doing what you’re doing,’” Lazar says. “And I said, ‘This is what I do.’” He then literally haggled with them over a new ICD trigger. “The doctor’s like, ‘Okay, let’s make it 195 for two and a half minutes,’” remembers Lazar. “And I was like, ‘Couldn’t you make it 200 for five minutes?’ It was like buying a mattress from Russians.”

Doctors jacked up the set rate and urged Lazar to slow down. For a while, he followed their advice. But eventually, he made a decision: He could survive, or he could live. He called a band meeting. “He sat us down and said, ‘Dude, don’t hold back,’” says Paris. “‘If I’m gonna die, I’m gonna fuckin’ die. Do it.’”

Sitting in his Greenpoint apartment, Lazar pulls off his white T-shirt to reveal the scarred convexity just above his left pectoral. There sits the central inspiration behind the Giraffes’ recent album, Prime Motivator, a collection of brutal, Zeppelinesque songs referencing hospitals, ICUs, and ambulances. “When I don’t feel so fine,” go the lyrics to the title track, “my machine makes up its mind … and it gives me some more time…” The ICD is hard to the touch, roughly the size and shape of an Altoids case. “I’ve been clipped on that by a door, and it fucking kills,” says Lazar. “Because you’re pinching skin between metal and metal.” As Lazar pulls his shirt back on over his head, a heart-shaped pendant swings six inches from the bulge of his ICD. It’s a gift from his girlfriend, with whom he recently broke up after ten years—months shy of their planned wedding. People who have near-death experiences often awaken with a transformed consciousness. For Lazar, the change came in stages. “I came out of it and thought ‘Okay, I can just go back to being the same old me, no big deal, got it,’” he says. “And then I remember being seized by ideas like, ‘I’m never gonna fall in love again.’ Well, I like falling in love. I don’t know how much time I got left. I gotta do this—whatever ‘this’ is.”

So he stopped penning jokey riot fantasies and started writing songs about life and death. And he gave himself over fully to the loud, rowdy rock-and-roll lifestyle—albeit with modifications: He must avoid metal detectors and microwave ovens (“There’s been the bizarre spectacle of someone turning on the microwave and me running out of the room,” he says), and since he must beware of magnets—used in most guitar amps and speakers—he’s permanently excused from sitting in the back of the van with the equipment. Sex is allowed. “The only thing is, if I do get defibbed, my partner could receive an unintended shock,” he says.

“I’m a cyborg for the rest of my natural life,” Lazar says matter-of-factly. “I guess I used to think of death as ‘sweet relief.’ You know, that whole abstract, romanticized goth idea. Now I know that’s horseshit. Death is straight-up annihilation, nothing else. It is truly ceasing to exist.” He takes a drag off a self-rolled cigarette. “For me, now, life, living, has become simultaneously more desperate and base but more beautiful.”

On a recent Saturday night in Williamsburg, scores of skinny-jeaned, artfully disheveled young souls are packed into the Union Pool, where the Giraffes are nearing the end of their set. Lazar, his black dress shirt unbuttoned to midchest, wields a fifth of Jameson as Paris begins the swaggering guitar riff of “Sugarbomb.” A girl screams, a beer can soars, and Lazar leans into the sex-as-ballistics love song.

Three minutes in, the song begins the climb to the tempo that triggered the first onstage defibrillation in rock history. Lazar continues to sing as the beat rises from 150 BPMs to 154 to 160 to 170. He grabs quick breaths, his chest heaving. Another can of beer soars toward the stage, raining foam. The air pulses with flashing lights and noise. Lazar is screaming atop it all in a fevered, raw-throated glossolalia, his dark hair plastered to his forehead, eyes shut tight, his lips curling into a smile.

BACKSTORY

Aaron Lazar’s career is a study in cross-pollination. At Kent State to study art, Lazar discovered both Iggy Pop and sculptor Richard Serra—dual influences on his later life. “Serra’s stuff, like the Torqued Ellipses—there’s something so fucking ballsy and wrong about it that I love. I think making one of his pieces probably gives him the feeling that being in a big, overblown rock band should, like someone could die from this.” When Lazar was in fine-arts graduate school at NYU, his professor, the video-art pioneer Peter Campus, suggested he start a band.

The Giraffes will play the Knitting Factory on June 18.