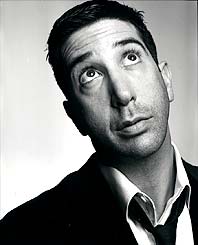

The first line of almost every article about David Schwimmer refers to Friends. He’d no doubt prefer that not to be the case. Because when Friends first comes up in our conversation (deep, deep into dinner), he doesn’t even call it by name. It’s “the series.” And like it or not, it’s the 39-year-old’s current legacy.

“It’s very strange to be known as a situation-comedy guy,” says Schwimmer, who’s about to have his Broadway debut in the entirely non-sitcom-like play The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial, opening May 7. Before the series, “I was mostly Serious Theater Guy,” he insists. “I definitely feel like I’m a stage actor first and foremost.”

Cue the laugh track, right? Well, perhaps not quite so quickly. In all fairness, Schwimmer is something of a theater person. He’s a founder of Chicago’s Lookingglass Theatre Company, and he recently appeared on the London stage in Neil LaBute’s Some Girl(s). (Plus he played alongside Larry David in the Curb Your Enthusiasm production of The Producers.)

And his quest to be taken seriously goes beyond the usual Hollywood-on-Broadway conundrum anyway. It’s a lot deeper than that. GQ may have once called Ross Geller “as cute as a wet retriever pup,” but Schwimmer himself is a bit, well, intense, even angst-ridden. He talks a lot about “trying to give a voice to those who have no voice.” He calls the objectification of women on MTV “disgusting.”

All of which makes him the perfect person to play Caine’s defense attorney, Barney Greenwald, because whether or not you buy the my-first-love-is-the-theater talk, there would appear to be much more Greenwald in David Schwimmer than there is Ross Geller. Called on to represent a naval lieutenant accused of mutiny, Greenwald is Jewish, impassioned, a tireless defender of underdogs, and someone with an unshakable moral center. Which is largely how Schwimmer would describe himself.

“There are many things I identified with,” he says of the part. “Being a Jewish man and kind of acknowledging what that means, being the son of lawyers and growing up loving the law. He’s got a very strong sense of knowing what’s right and what’s wrong. It’s one thing to know the right thing. It’s another to say what you should say in a given situation, instead of swallowing it.”

Not a lot of actors, for example, would unself-consciously proffer this tidbit: “If someone in a work environment says a racist joke, I’m the kind of person who says, ‘I’m sorry, I don’t find that funny, and I’d appreciate if you don’t tell those kinds of jokes when I’m around.’ And you can be looked at as, ‘Wow, he’s the bummer in the party.’ But I just don’t go for that.”

Schwimmer had wanted to try Broadway for a while, “and a couple of things came up that just never quite felt right. Either because I liked the play but wasn’t hot on the director, or there was another star attached that I wasn’t jazzed about working with.” Then his agent showed him Herman Wouk’s 1954 stage adaptation of his Pulitzer Prize–winning novel—“and I was just shocked at how good the writing was.”

The courtroom drama also features Wings’s Tim Daly as Schwimmer’s legal opponent and Zeljko Ivanek (The Pillowman) as Philip Francis Queeg, the captain who may or may not have mentally unraveled mid-typhoon. Wouk himself consulted on the production, Jerry Zaks is directing, and the show is running in the Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre, home to the original production—making The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial a rather high-profile way for Schwimmer to open in New York.

And so he’s been trying very hard to get things right. In preparation for his role as a defender with a seemingly unwinnable case, Schwimmer sent copies of the play to his lawyer-parents in L.A., where he grew up (he now lives in a loft here). “They each returned the script to me filled with Post-its from top to bottom.” He says he relates to Greenwald for his “philosophical sense of human suffering,” and he becomes particularly animated when talking about the political implications of staging a wartime play while the country is at war.

“I don’t think the idea for doing this play came from a specific political agenda,” he says. “But for me personally, I had to read it many times and think a lot about what it’s saying. Because I don’t want particularly to be involved with something that says something other than what I believe. I think it gives the audience the credit that it will differentiate between being respectful and supportive of our military and being critical of whatever the current administration is.

“When push comes to shove,” he adds, “the military’s just a tool. I really take offense when I hear people say, ‘Aw, man, I can’t believe what the military’s doing.’ It’s like, it’s not the military. And it’s infuriating to me when people are outspoken about the war and are labeled immediately as un-American. That’s a crock of shit.”

His seriousness now firmly established, there remains the question (that conundrum again) of whether people will take him seriously as an actor. “Yes, I’m healthfully concerned about reviewers ripping this apart,” he says. “Maybe they’ll pick on me because this is my first time on Broadway.” In a way, he’s about to face a level of media glare that he’s been spared from for a while, even if it won’t begin to approximate the experience of his good friend, tabloid mainstay Jennifer Aniston. (“I don’t presume to know how she feels about it,” he says. “Most of the time I feel sad about it. I feel grateful that I’m not under that kind of scrutiny.”)

“If someone in a work environment says a racist joke, I’m the kind of person who says, ‘I’m sorry, I don’t find that funny.’ ”

The attention Schwimmer garnered during Friends has abated, naturally, and though his film career hasn’t attained Must-See-TV heights in the two years since the show went off the air, he doesn’t seem to miss the experience much. “I’m incredibly grateful for everything it gave me,” he says. “Not the least of which was the financial stability to now do whatever the hell I want. But I really don’t think about it, unless I’m being asked. How often do you think about your high school?”

But shaking a ten-year character like Ross can be complicated, whether you’re dealing with critics or castmates. “It’s weird,” he says of how he’s viewed by his Caine colleagues, whom he likes a lot. “A big thing for me is the other actors. My feeling is there’s just no room for anyone’s ego. Thank God we’ve been really lucky—there’s twenty guys in the cast, and it’s a great group.”

That doesn’t mean, however, that between-scene bonding has come easily. “I enter a process like this with a completely clean slate,” says Schwimmer. “And I honestly forget that people would be less inclined to say, ‘Hey, you want to grab lunch?’ Just because of who they think I might be. So I sometimes think, Wow, these guys aren’t very friendly to me—they’re asking everybody else if they want to get a bite to eat. And then I realize, Oh, fuck, that’s right. So I make the effort.”