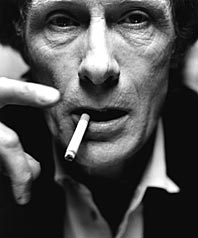

Meeting an actor whose work you love can be disillusioning, but lunch with Bill Nighy—he’s on Broadway opposite Julianne Moore in David Hare’s The Vertical Hour—is a treat, as well as a rare opportunity to explore the connection between performance and neurosis. No, I’m not calling him a neurotic. It’s Nighy who, when asked to account for his busy, tortured deadpan, brings up the possibility of a mental disorder. My take is that, in working through his peculiar self-disregard, he has produced some of the subtlest, most charming, most affecting comic stylings in modern movies.

The 56-year-old Englishman is not just hugely in demand, he’s even something of a sex symbol—and as I write that, I can hear him give a little snort, the same snort (it’s less derisive than morbid) that turns up in many of his performances. I heard it first in a small ensemble movie called Lawless Heart (2001), in which he plays Dan, a farmer who longs to have an affair with a florist but can’t summon the courage. The directors devised the script based on actors’ improvisations, and the key lines came from Nighy—like the bit where the stuporous Dan muses he’s “rather flattered” to be called “depressed”: “I suppose I have emotions,” he says, “but I don’t make a meal of them.”

The part he made a meal of—that broke him out—was Billy Mack, the washed-up rocker in Richard Curtis’s Love Actually (2003). Billy is Nighy’s antithesis, a man who feels he has nothing left to lose and therefore no shame. Except, of course, shame bleeds through his every obscene utterance about the rottenness of his new record. Nighy once—but no longer—led a “happy-go-lucky chemical life,” and the director, he says, responded to his look of “someone who worked nights.”

Then Curtis turned around and wrote for Nighy the part of Lawrence, the painfully shy government bureaucrat in the HBO movie The Girl in the Café—a man who can barely take a step without second-guessing himself. “By that time, he knew me better,” says Nighy. “Eating alone in Thai restaurants is a large part of my life, because my wife [Diana Quick] is an actress and therefore we’re always apart.” Bringing out every last note of Lawrence’s phobia was oddly comfortable for Nighy—it was like singing the blues. “To be disabled to that degree by self-consciousness is not something that is unfamiliar to me or, I imagine, to most people. It requires a degree of courage to interact with the rest of the world.”

Over lunch, Nighy overcomes his social disabilities with courtly grace, although his two-fingered handshake suggests there’s only so far he can go in the direction of intimacy. His manner evokes his most emblematic performances, in which there is a continual shift between elegance and awkwardness, utter poise and utter collapse. “It amuses me,” he says, “the idea of that stop-start, tense-relax, strike a pose–fall apart kind of thing.”

I ask if he feels at home in his lanky body, and the question takes him aback. “I shower in the dark,” he says, by and by. “I’m not particularly keen on the sight of myself, to a kind of extreme degree. I know it’s nuts, because I’m perfectly acceptable-looking, but it is a reality … It’s not modesty, it’s not coyness, it’s not affectation. I wish it were because it’s caused me an enormous amount of trouble … ”

It’s also, I suggest, the fount of his comedy.

“It seems I have an enthusiasm for how I arrange my bones. It’s entirely unconscious, and I’m unaware of it unless somebody refers to it. I remember I tried to go out with a dancer when I was young. And she said, ‘Do you realize that you spend a large part of the evening in first position?’ ”

The first position, it emerges, is a metaphor for the idea that every second he’s trying to tell a story—to sum up a character—in his face and body. When he was younger, directors were always telling him he was insane, and to stop it. “My nickname was Nerve when I was a kid,” he explains. “And it sounds good when it’s shortened, but in fact it was shortened from ‘Nervous.’ Because I never sat down. I was always on edge.”

I ask him whether, in The Vertical Hour, where he plays a physician who’s left a thriving city practice after a tragedy and retreated to the edge of the world (well, near Wales), he had a process to help overcome anxiety. “People used to sit around on tour in rooms after shows discussing their process,” he says, “and I just used to shut up during that part of the conversation, because I didn’t have one.”

In fact, he says, he spent years onstage paralyzed. “I’d have conversations with myself about why I’d just put my left hand in my pocket,” Nighy recalls. “ ‘And what are you going to do now? Are you going to move it? Well move it, take it out, that’s what people do.’ ‘No I can’t move the arm.’ ‘Just put it there.’ ‘Why would you put it there?’ And in the end I’d just stand there and do nothing.

“So I’m very good at inventing a hostile parallel universe and living there for a while. And maybe I shouldn’t bring this up”—but, he admits, it wasn’t a process that inspired him to throw off the shackles of self-doubt but a Dame: Judi Dench, with whom he acted in The Seagull at London’s National Theatre in the mid-nineties. He says there was a moment before he went onstage one night when he just “let go”—and was never the same. Nighy will appear with Dame Judi in a juicy crypto-lesbian psychodrama, Notes on a Scandal, that opens in December, and has given a lot of thought to why he reveres her. “She has the courage to arrange to arrive onstage unarmed,” he says. “She’s defenseless. She walks on and lets it happen to her. I wouldn’t claim to understand it, any more than I’m sure she would, but it is something mysterious and beautiful. The air kind of changes.”

With Dench, Moore, and Cate Blanchett (also in Notes on a Scandal), the air around Nighy is rarefied indeed, and in the spring he’ll return (transformed by CGI) as the mandibled demon Davy Jones in the third chapter of Pirates of the Caribbean. One can almost imagine Bill Nighy exulting in his newfound stature—

“Is this all right, or am I talking bollocks?” he asks. “I know when I go away I’m going to have post-interview trauma or something because I always think … Anyway, don’t worry, don’t panic. What was I saying?”

Never mind.

BACKSTORY

On the strength of his gaunt physique and mummified delivery, Nighy made an elegant vampire lord in Underworld. He rejoined the ranks of the undead in 2004, when he played the stepdad in Shaun of the Dead—a man groggy with middle-class angst who becomes fully alive only on the brink of zombiehood. The role draws on his own dad, whom Nighy describes as “comically and very endearingly socially disabled.”