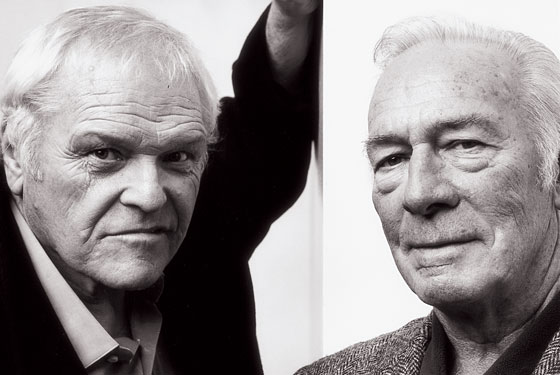

When Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee wrote Inherit the Wind more than a half-century ago, they didn’t have southern Evangelicals in their crosshairs so much as McCarthyites—the Scopes “monkey” trial, of which their play is a fictional rendering, simply seemed like the right vehicle to send a message about fearmongering, censorship, and the perils of anti-intellectualism. Had they known that creationism would remain a topic of serious debate in 2007, perhaps they’d have taken up the subject matter with more urgency (or hewed a bit more closely to the historical record), but never mind: Inherit the Wind, which opens this week, still makes terrible modern sense. Brian Dennehy, 68, and Christopher Plummer, 77, who have 88 years of stage and film experience between them, weigh in on their roles as Matthew Harrison Brady and Henry Drummond (William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow, respectively), as well as the hedonism of the sixties, the changing role of the theater, and the vulgarity of ringing cell phones.

How did you two meet?

BD: We met a couple of times before. When we did this picture about the priests called Our Fathers—

CP: Well, that’s when we really met. But I first met you in our drinking days, which is why I can’t remember you at all.

BD: Is that right?

CP: You see? Exactly. Yes, we met.

BD: I’m in London two years ago and I bump into Ray Davies of the Kinks. And he says, “Hi!” and I say, “Ray! It’s a pleasure to meet you.” And he says, “What ya mean, fuckin’ meet me? We fuckin’ sat on a fuckin’ airplane from Los Angeles all the way to fuckin’ London and drank about three fuckin’ bot’les o’ Scotch.”

CP: Was that in the sixties or the seventies?

BD: Must have been in the seventies.

CP: I don’t remember most of the sixties. It was great. I was in London, which was the place to be, so they tell me.

BD: I was in the fucking Marines. And tending bar on the Upper East Side, fighting off deranged, drunken firemen.

If we could discuss this play for a moment—Christopher, were you on Broadway when it debuted in 1955?

CP: Yes. I went to see it, but I don’t remember that much about it, because I drank my way through the fifties as well.

BD: To me, what’s interesting is that the construct of the play is Darwinian. These guys [the playwrights] use the characters and the facts of the trial to essentially move their audience away from the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. They elevated the great individualist, Darrow … and Bryan, a nineteenth-century traditionalist, is sacrificed. Darrow survives. I mean, it’s a message play. Which doesn’t mean it isn’t entertaining. The second act—the debate, the confrontation—is beautifully written.

Do you think theater still has an impact? Considering that millions can see An Inconvenient Truth in just a few months …

BD: Depends on what you mean by impact. I think what happens in the theater, when it happens, can’t happen anyplace else. When I saw Chris’s Lear, there’s this one line where he says, “O, let me not be mad.” Now, you read that line and realize it’s a strong line. But when you see an actor at the top of his form saying it—and not in a hugely emotional way, but in this heartfelt way of an older man saying, Christ, I don’t want to be nuts—it goes right to your fucking heart. It resonates in my head in a way that no movie or documentary or television show can do. It’s like the first time I saw [Van Gogh’s] Sunflowers in Chicago. It stops you. You fucking stop. It’s this big room, small painting, and you stand there for a minute, if you’re like me, and say, Jesus Christ.

CP: Peter Brook said it once: There’s nothing more exciting or more barbaric or more basic than one person walking onto an empty stage. And I think he’s absolutely right. It’s lasted 2,500 years as we know it, anyway, the theater. So it must have worked.

BD: Theater has never been a consumer product. It can’t be. How many people saw Shakespearean plays? Although the old Globe did hold a lot of people, right? Like 1,500 or 2,000.

CP: There were a lot of people on the stage as well. The whole audience sitting there, giving you trouble.

Which is what you’re contending with now, right? I was surprised to see a few rows of the audience seated behind you, on the actual stage, acting as jury. How is that? Disconcerting?

CP: No. I thought it was going to be ghastly. I was afraid there was going to be some mad … idiot up there—

Heckler, you mean?

CP: Yes! And maybe one night we’ll still get one. But so far they’ve been terribly, terribly well behaved. Except the three kids the other night.

BD: I didn’t notice them.

CP: They were in the front, looking at the ceiling [leans back, pretends to drool].

Gene Hackman once told me that the first time he performed onstage, he found the lines of his co-star—who I gather was quite old—scribbled all over the back of the couch. Do you have anything written down?

CP: Oh, yes. I’ve got them on my desk [onstage], a couple of lines I can never remember. I had to write them down because they’re legalese.

BD: He was almost word perfect at the first rehearsal. I said to him, “You son of a bitch. You’ve been studying your lines.”

Has a cell phone gone off yet?

BD and CP: Not yet.

You have a method of dealing with them, yes?

BD: Depends. If the phone rings three times and stops, I do nothing. It’s when the phone rings and the guy pretends, It’s not mine—that drives me crazy. I remember one time in Chicago the phone was ringing and ringing, and I looked up and said, “All right, we’ll wait. And you better be an obstetrician.”

Which play was this?

BD: Hughie. It’s a one-act play! How could he do that in a one-act play? I said that to him: “I could understand the phone going off in the second act, but this is a one-act play!”

You said this from the stage?

BD: Yeah! What the hell are you going to do? The play stops. So you stop the play.

CP: Yeah, it was easier when I did Barrymore, because it’s a one-man sort of evening—you spoke to the audience all night long.

So what’d you say if a cell phone rang?

CP: “I’ll get it.”

BD: Remember when Laurence Fishburne was in The Lion in Winter? He says, “You stupid motherfucker, answer that motherfuckin’—” Talk about getting out of character.

CP: You have to acknowledge it. Otherwise, you’re dead.

BD: I was doing Trumbo once. About a blacklisted writer, attracted primarily Upper West Side intellectuals, an audience of a certain age. And we had an older man one night who had a bowel movement. We didn’t even know it at the time. All of a sudden, the crowd had a reaction.

[To Plummer] And you say the theater still has a future?

CP: That probably happened 2,500 years ago, too. In the Greek days, they probably dumped in the second act, and why not? There was nowhere else to go in those days.

You two must have some interesting stage-door stories, too.

BD: You know what’s funny now? You have this phenomenon where it’s the same guys, and they come three, four, five times a week, and they all have five photographs for you to sign, and you look at them and know they don’t give a shit about you or your performance—

Oh, God, eBay.

BD: Exactly. So one night, I ask one of them, “How much can you get for the five hundredth copy of my signature?” And he says, “I sell them for five bucks, seven bucks, people buy ’em. I go from this theater to that … ”

CP: On the other hand, way back in the prehistoric days on Broadway when I began, there was a group of very loyal fans that used to stand outside the door. Celia was a woman whose name was famous all over town. She was this funny little, rather homeless-looking type. I’m sure she couldn’t afford to see the plays, but she loved the actors, and she headed this little group of fans that hung around with her. Every year she was outside the stage door … until she died. And everybody missed her.

Brian, you had some interesting actors come visit you after Death of a Salesman each night, didn’t you?

BD: My favorite was Robert Goulet. I was six months into the run and looking at six months more. And he said, “Wonderful, but how do you do that with your voice?” And I say, “My voice?” And he says, “You’re working on the edge of your voice! You’re not using the central part of your voice!” Worst fucking thing you can say to an actor. Within a week … [starts whispering inaudibly]

CP: There’s this famous story, if I may say one or two words …

BD: I’m not finished.

CP: My God, your story’s not finished?

BD: Go ahead …

CP: So Dame Sybil Thorndike—the great old actress who died ages ago, I met her once or twice, and she had an extraordinary story: When she first played Medea in London, Dame Lillian Braithwaite, who was older than she and had been a great Medea, came to one Saturday matinee. She was sitting out in the front row with her companion. She was very old. And poor Sybil was trying so hard to be so great that particular day. She had a wonderful voice and was trying to boom it out. And Dame Lillian—the minute she sat down, she fell instantly to sleep and slept through the entire first act. So in the second act, Sybil decided to really lay it on. She screamed something about “My children are dead and I’m going up to the sun,” or whatever the hell the line was, and suddenly Lillian Braithwaite woke up and said in a loud voice, “Is there someone in the room?”

Is there a role you think you’ve never figured out?

CP: Hamlet. I don’t think anyone is the definitive Hamlet. It’s just not possible … and neither is Lear. And Macbeth certainly isn’t. Everyone has failed miserably at Macbeth.

BD: Yeah, Macbeth is a strange one.

CP: It looks so clear!

BD: So clear, and you think, This can’t be that hard—until you do it.

But Hamlet’s more elusive to you, Christopher, than Macbeth?

CP: Well, I really know a lot about Hamlet.

BD: I saw Richard Harris just before he died; he was 68, 70—you must have gone drinking with him, right?

CP: Oh, yes.

BD: And he said, “I think I’m going to do Hamlet.” And I said, “What?” And he said, “I think I’ve finally matured enough to understand him.”