The Tony awards this Sunday are hardly ample enough to do credit to the fine crop of plays the recent season produced. European classics, contemporary comedy, American masterworks, and new work by youngish writers were all represented in unimpeachable productions. This surprising robustness makes it all the more noticeable, and all the more sad, that something was seriously wrong with the musicals. But what was the disease giving so many of them the same livid complexion? Call it emphasitis: the enervating result of a synesthetic assault on the audience’s attention by talented people overdoing everything.

Some of the symptoms—such as painfully loud sound design—have been developing for years but broke through in a new way this season. At Rock of Ages, a show that imprisons you for two hours between a woofer and a tweeter, the cacophony for the first time seemed intentional: a way of obscuring the cheesy story and driving the sale of drinks. The producers would do well to sell earplugs too—but earplugs are no longer enough. The current revival of Guys and Dolls, building on the innovations in computer-graphic nausea inducement pioneered a few years back by The Woman in White, would benefit from eye-plugs. A good guideline is that your set design should never feature more dimensions than your cast.

What’s troubling this year is how pervasive the problem has become, creating a new baseline of “theatricality” that even top directors and performers seem powerless to resist. At its worst, that theatricality replaces subtlety, slyness, and variety of tone with the kind of constantly on-point, drilled-home messaging formerly reserved for ADHD teenagers. Indeed, the likeliest vectors of emphasitis are the blockbuster entertainments geared to those teenagers. Desperately trying to attain the condition (and thus the audience) of summer films, many musicals so overstep their welcome that the drama becomes one of managing the intrusion and getting out unharmed.

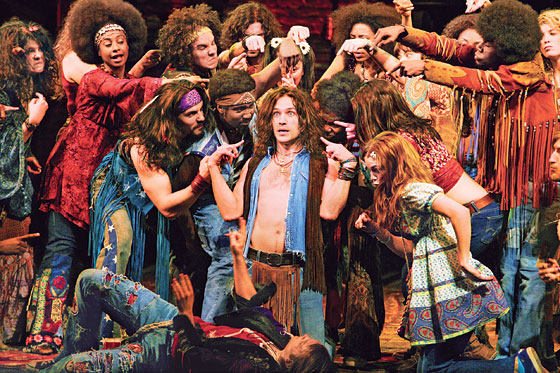

When Hal Prince and Michael Bennett first used approximations of cinematic techniques to mimic the effects of close-ups, jump cuts, and montages onstage, they weren’t trying to make movies. They wanted the swiftness and focus the camera allowed while retaining the core theatrical value of letting individuals think for themselves. By now, though, the perfection of movielike tricks for manipulating audiences has progressed to such an extent that the one theatrical convention film can’t replicate—the live and voluntary interaction of actor and viewer—no longer registers as such. When the cast of Hair descends from the stage, flailing patrons’ faces with their sweaty locks, you may fear that you have been transported into some new amalgam of Sensurround and Smell-O-Vision developed for a mutant-spider movie. And when the audience is later invited to join the “spontaneous” be-in onstage, it’s a Purple Rose of Cairo moment. The drama hasn’t been presented so much as you’ve been admonished to join it.

At least you can say no. And Hair is a touching revival in part because of its doggy overeagerness. But shows of more recent vintage, even or especially those with admirably high aims, don’t seem to feel they can take a chance on the audience’s willingness. Next to Normal does exactly what critics have been begging new musicals to do for ages: address serious themes—in this case, mental illness—in a contemporary idiom. The quasi-rock score is certainly successful at maintaining the requisite atmosphere of anxiety, but despite its virtues and the talent of its creators, Next to Normal constantly overplays its hand. (Also its feet; why so much running around the three-level set?) The heroine’s electroshock therapy is indicated with blinding flashes of light and hair-raising power chords, a form of underlining that short-circuits sadness or concern—or any response one might choose to have—and replaces it with something more reflexive, like fear. (Anyone who has seen electroshock administered knows it is the silence, the absence of indicators, that makes it upsetting.) The direction of this scene, as so many others, asks the audience to share the characters’ experience, not have its own. It’s a kind of electroshock-by-proxy.

The excellent cast does its best to sell the story at the pitch required, but songs deliberately written—as so many now are—to test the boundaries of human endurance inevitably get wearying. Many who admire Alice Ripley’s bravura performance as the bipolar mom nevertheless leave the theater worried more about her voice than about her character’s fate.

Such measures are hardly unique; mugging, which used to be a problem outside the theaters, has now become epidemic within. (West Side Story’s Jets put on “mean faces” to show they’re not just dancers and as a result look pretty much like Billy Elliot’s fanatically grimacing ballet girls.) The problem of overstatement in direction, choreography, design, sound, and performance is now so entrenched as to make moments of relative calm (such as Allison Janney’s underplaying in 9 to 5) seem like genius.

I hasten to add that Billy Elliot and Next to Normal are worthy shows that deserve long runs. But there is collateral damage. The shiny too-muchness that’s now de rigueur puts quieter, less aggressive entertainments, whether musicals or plays, in a false frame. True, they sometimes belong there: The Story of My Life was quiet enough for a librarians’ convention and too anemic for anyone else.

But material of a different temperature is muscled out indiscriminately, consigning chancy dramas like Lynn Nottage’s Ruined and eccentric star turns like Sherie Rene Scott in Everyday Rapture to limited runs Off Broadway. Worse, modest productions with much to offer get bullied as weaklings. The current revival of Samson Raphaelson’s Accent on Youth, a fascinating example of an earlier brand of American dramaturgy that involves no confetti cannons, was greeted with what can only be called angry yawns. And last season’s deeply moving A Catered Affair was received as if it was a rebuke to the new style. In a way, it was: Its high point was a scene in which Faith Prince stood in dead silence for 50 seconds, thinking. Unfortunately, that may be the last time you see anyone think in a Broadway musical, because 50 seconds is about as long as the show managed to run.

The Tony Awards

CBS.

June 7 at 8 p.m.