Last year, an enchanting production settled briefly at Brooklyn’s St. Ann’s Warehouse. It was based on the 1945 Noël Coward and David Lean film Brief Encounter, about a young doctor, Alec, and a housewife, Laura, who meet in a train station. Both are married but yearn for something the other provides. The theatrical version, which originated at Britain’s Kneehigh Theatre, expanded on the black-and-white film through colorful characters, song and dance, and endless bits of whimsy, without ever sacrificing Coward’s deeply romantic and tragic vision. And now it’s back, this time on Broadway. The imaginative forces behind the play—director Emma Rice, an actress and choreographer, and Neil Murray, a painter turned scene-and-costume designer—agreed to talk about the show’s evolution, which began in a cluster of seaside barns in Cornwall, England, where Murray created these early sketches “as a means of finding a poetic landscape to think and live in and grow from.”

From the moment you walk into the theater, you are transported to another time and place”specifically, thirties England, just before World War II. Rice and Murray were after an atmosphere that combined the theatrical with the “looser, more bawdy” feeling of a music hall or cinema. At times, the actors appear to slip into the original film, which is projected onto elastic screens at the back of the stage. Murray describes their process as figuring out a way to “juxtapose odd elements that wouldn’t normally sit together.” Photo: Kevin Berne

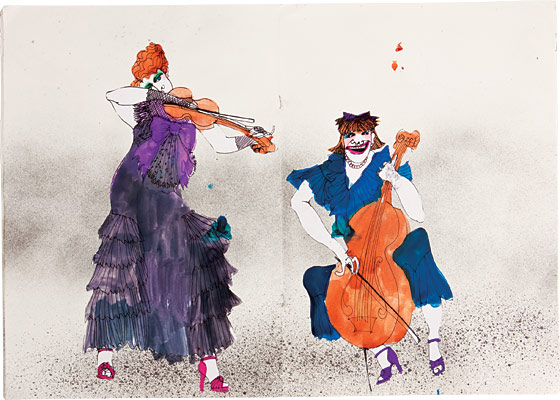

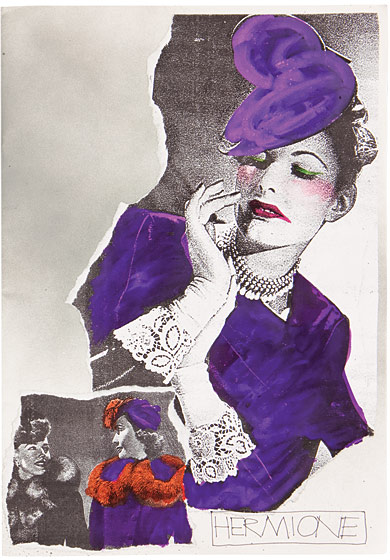

Murray is always more inspired by mood than by a specific look. He has “trillions” of reference photocopies from past productions he’s worked on, but “it’s not about, “Oh, I want one of those.’” In this case, Murray was attracted only to the woman’s expression: “It’s slightly nasty, superficial.” It inspired two characters, friends of Laura’s who are “English middle-class snobs ” They know what the score is. It’s unsaid and not very nice.” Photo: Boru O’Brien O’Connell/New York Magazine

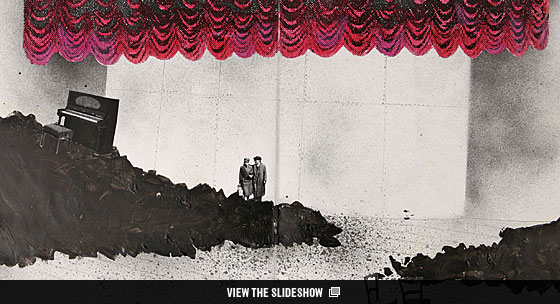

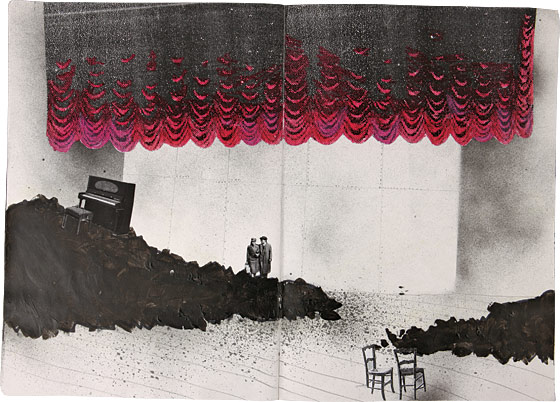

In this early, inspirational sketch, coal figures heavily, as it does in the play, beginning with the first meeting of Alec and Laura: He plucks a cinder from her eye. But coal also speaks to the heat of the repressed lovers’ passion and to Alec’s vocation, preventive medicine for the working classes. Photo: Boru O’Brien O’Connell/New York Magazine

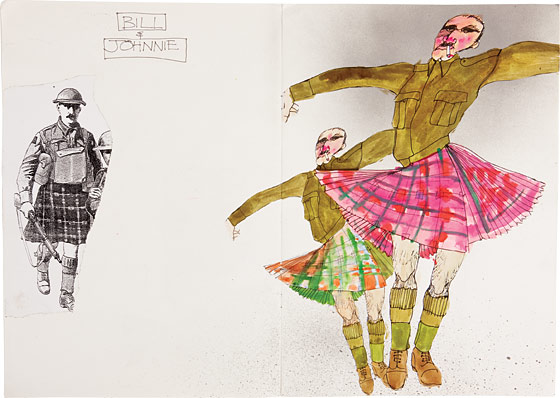

Soldiers move in and out of the production. “We originally put them in kilts because we thought it would be kind of fun and distinctive”“with the occasional bottom revealed, says Rice. As the show evolved, she and Murray came to see that “in fact, they’re not at all funny. They’re about war coming. I wanted that sense of foreboding.” Photo: Boru O’Brien O’Connell/New York Magazine

Rachmaninoff’s rapturous Piano Concerto No. 2 is central to the film’s score, but Rice and Murray shied away from relying on it. “Putting the Russian expression next to the British repression, there was an amazing chemistry,” Rice says. “I knew I couldn’t steal that.” So she latched on to an early line of Laura’s”“I used to play the piano as a child, but my husband’s not very musical at all””viewing the piano as symbolic of the passions she lost to marriage. An upright sits on the stage for much of the production (the top doubling as the train-station café’s counter), but Laura plays it”and Rachmaninoff” only once, at the very end. Photo: Kevin Berne

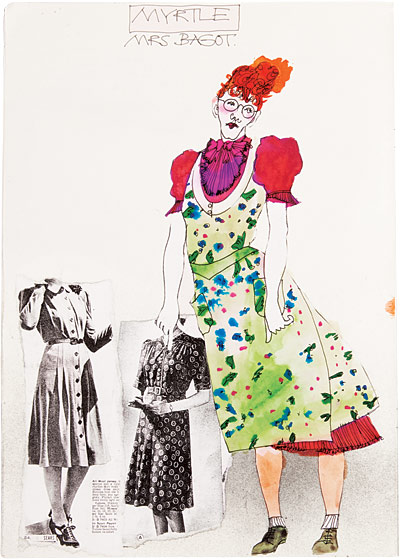

Myrtle, the bossy owner of the station’s tea shop, “has a slightly dominatrix feel in the show now. We’ve padded her bottom, padded her breasts.” Rice wanted her to “fill the space, own the space” as a subtle nod to the politics of a working woman living independently. “She has a very nice white apron now, which is a little bit cheeky,” adds Murray. Photo: Boru O’Brien O’Connell/New York Magazine