Uplit like a Renaissance virgin by the glow of her iPad, the director Julie Taymor watches with mounting excitement as a gigantic black net unspools from a kind of coffin beneath the stage. The net is supposed to whoosh up, but like everything else to do with Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark, the job takes longer than expected. Indeed, in its first outing, the effect is less special than glacial, but Taymor’s half-smile doesn’t fade, even as ten stagehands scramble to keep the mesh from snagging as it rises. Anything that works beautifully, she knows, once didn’t. Especially anything big. It happened just across 42nd Street at the New Amsterdam Theatre with The Lion King in 1997; surely it will happen again here at the Foxwoods.

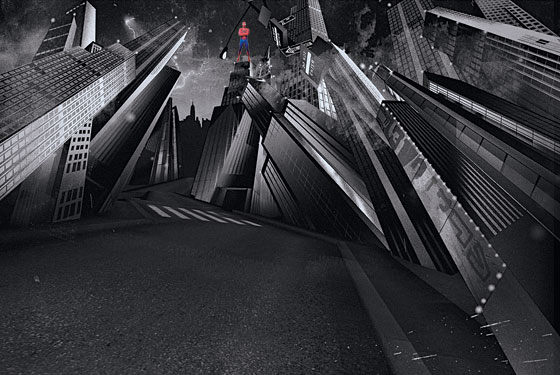

That the theater, formerly the Hilton, was recently renamed for a casino is lost on no one working within it these days. Every step seems like a giant gamble—often literally. When the winches stop winching, and the net reaches its full extension, a guy on a wire drops down from the flies to test it. Can he leap from place to place? Can he climb it upside-down? Can he do these while battling an eight-legged, part-human, part-marionette villain called Arachne, who enters the scene through a sky-high portal nicknamed “the A-hole”? A lot depends on the answers, because these movements, if they turn out to be feasible and safe, and if they adequately replicate the vision Taymor had of them so long ago, will be part of the climax of the $400 billion new musical: a scene in which Peter Parker, trapped in his enemy’s web, must learn to embrace his power or die.

Did I say $400 billion? Well, no. “All those budgets that everyone quotes are fantasies,” says Michael Cohl, the show’s lead producer, referring to the obsessive, Schadenfreudish coverage that has greeted every aspect of Spider-Man, especially the financial aspect, since it was first announced. “They are like asking my dog ‘How much is the budget?’ and counting how many times he barks.”

Okay, then: Imagine that Sparky barks 70 million times, and you’ll be in the vicinity. Certainly Spider-Man is by far the most expensive Broadway show ever produced, though not so expensive compared with, say, a blockbuster movie or a stadium rock concert or a Cirque du Soleil spectacular, with each of which it shares DNA. Furthermore, says Taymor, “why should the press care if five or six billionaires want to put out their money and 200 theater people are employed as a result? This is a drama–rock-and-roll–circus, or a circus–rock-and-roll–drama; there’s no word for it. And what do they want? Two-character, one-set musicals? How is that helping the theater?”

Whatever the cost, and the value of that cost, it soon becomes clear that the web isn’t working: It’s not just slow; it’s ungainly. The climber looks trapped all right, but not in a good way. His harness keeps catching on the fabric, his sneakers slip through the webbing. When the shredding noises start, and two-inch metal grommets start zinging into the orchestra, most people might decide it’s time to give up.

But not Taymor. Seated amid a sea of computers that makes the theater resemble NASA mission control, the tiny figure in her giant contraption is not the least bit worried. She turns on her “God mike” and, in the artificially lowered voice she has learned to use in order to sound calm and authoritative, suggests that a narrower mesh might solve the problem, or tighter rigging, or both. If these measures fail, she adds with the microphone off, she’ll come up with something else, just as she did when the huge steel “flying ring” that had been built and hoisted into the rococo dome of the theater turned out to be a dud. (That one lasted two days.) “Let’s wait and see,” she concludes, as designers make notes for ordering a new net and Sparky barks again.

Forget that as she says this, as the net slinks back into its coffin, the first preview, then scheduled for November 14, is just twelve days away. To judge from the conditions in the theater, where tech rehearsals, after seven weeks, are still bogged down in the middle of Act Two, they will never make it. (Most shows, admittedly much less complex, complete their tech in two or three weeks; eventually this one will take nearly twelve.) Recognizing this, the producers, on November 5, announce a delay of two weeks, even though it will cost them at least another million in ticket revenue from thirteen heavily sold houses. (Previews are now scheduled to begin this Sunday, November 28; opening night, also delayed, will be January 11.) “Shows like ours, that embrace the challenge of opening on Broadway without an out-of-town tryout,” Cohl announces, “often need to adjust their schedules along the way.”

Often is right. Much has transpired in the eight and a half years since Tony Adams, the original producer, having struck what some insiders say was a crippling deal with Marvel for the stage rights, approached Bono and the Edge, of the rock group U2, about writing the songs. They in turn approached Taymor, then finishing her movie Frida, to direct. (“We were only going to do it if we could do it with Julie,” says Bono, who had loved The Lion King.) After reading through the original comic books and realizing that they offered “a mythology as authentic as any other,” she agreed. “Every age has its own myth that becomes more potent than others,” she says. “And this is ours.”

As it turned out, there was something aptly mythic about the ensuing saga as well. In 2005, after wrangling the complicated contracts for three years, Adams dropped dead of a stroke in the Edge’s New York apartment just as the guitarist was getting his pen to sign. Adams’s business partner, David Garfinkle, a lawyer with virtually no previous producing experience, took over and gradually ran the show into the ground. Funds he felt sure he’d secured would prove not to be so secure after all. In the meantime, Taymor and the others kept working; designers were hired, sets were built, expensive flying workshops were held in Los Angeles. Predictably, the budget, originally projected to be $25 million, kept expanding as the bank account drained.

Still, when Young Frankenstein announced it would close in January 2009, Garfinkle booked the Hilton and began massive renovations to accommodate the new show. No one blinked; many movies costing much more have gone on to recoup. That movies have studios behind them, while Spider-Man had only Garfinkle and a lot of promises, was something no one worried about until the press began reporting, that fall, that the show could no longer pay its bills. Bono, blindsided, asked Cohl, who as the head of Live Nation had produced some of U2’s biggest and most successful tours, to take over. In part because he was already an investor and wanted to make good on his investment, and in part because Bono assured him he could do it “as a side job,” Cohl said yes.

Then he had a look at the books.

How did he find the show’s finances? “That I can summarize in one word,” he says. “Bankrupt.”

Thus began a mad scramble to reorganize, renegotiate, and recapitalize—a process made more difficult by the collapse of the economy and the project’s reputation. Some potential saviors didn’t like the story; some didn’t like the deal. (Garfinkle, shoved aside, retains a producer credit.) By then, too, lead actors including Alan Cumming and Evan Rachel Wood had dropped out, citing scheduling problems. For six months, while the theater stood empty and rent kept coming due, Cohl and his general managers hammered out budget after budget, only to find that in the time it took to do so, their original assumptions had gone stale. Set pieces they thought were in storage turned out to have been dismantled for scrap. “We were chasing our own tails,” he says.

Finally, having secured “tens of millions” in additional funds, Cohl stabilized the production enough to restart the renovations in February. Rehearsals began in August, and in September the company moved into the Foxwoods. Soon Taymor began to see (and immediately start rejiggering) the amazing stage pictures she’d been sitting on for years. But as jaw-dropping as the show looked in the theater—and the effects are miles beyond any use of flying, LED screens, and animation I’ve ever seen on a Broadway stage—doubters say it’s not enough to compensate for the third of the capitalization that got “flushed” along the way.

Still, forget all that. Taymor would certainly like to. Money doesn’t interest her except as a means to an end. When a lighting designer shows her the difference between the red achievable with one kind of fixture versus the far richer red achievable with a more expensive one, what a surprise, she picks the latter. “That’s all I need to hear,” says the designer, scurrying off. No, Taymor would rather talk about the meaning of spider myths, the function of theater in society, and the role of the shaman in theater. (Bono calls her a “sha-woman.”) She’d even rather talk about the hush-hush Arachne, whom she invented after having a dream in 2002 about a “boy being torn between his mundane, everyday, but important life” and the gift of his supernatural power. “Our theme,” she realized then, “is ‘Rise Above’ ”—which Bono and the Edge soon fashioned into a classic Broadway ballad that sounds like what the Beatles might have written if they’d studied with Irving Berlin. “If you could be anything, what would you be?” Taymor says, summarizing the message. “Understanding, of course, the potential to fail or go overboard.”

Marvel, though fiercely protective of its brand, approved many of Taymor’s inventions, not just Arachne but also a “geek chorus” of comic-book fans, a living switchblade of a villain called Swiss Miss, and, indeed, the whole structure of the drama. The bright-colored, plot-heavy first act basically tells a version of the familiar origin story: Bullied boy acquires special skills as the result of a mutated-spider bite; he gets revenge and confronts Green Goblin while bashfully courting the beautiful (and, in Taymor’s version, abused) Mary Jane. But Act Two consists almost entirely of new material. It takes Peter on a more symbolic moral journey, like the ones Taymor came to love in her studies of world theater, in which, as she describes them, enemies are both external and internal, and the gravest danger is hubris.

When she talks this way, with the redoubled fervor of an anthropologist and an autobiographer, she’s spellbinding—which is how she gets some fairly imposing people to part with their money or subordinate their vision to hers. Bono, who admits he has sharp elbows too, says she wasn’t shy about telling him and the Edge what she wanted. “Oh God, no. And I say that with relief. If you were looking for a partner you could placate or enjoy easy criticism from, you would be looking in the wrong place. Myself and Edge have never worked with anyone more intense than us—until Julie. But here’s the thing: That combative, punchy style in conversation is why I’m in a band. You’re as good as the arguments you get.”

The score is rich in angsty ballads and nervous riffs, with impressionistic lyrics like “There’s no time for sorrow when there’s no such thing as time.” Taymor says, “You don’t even know what that means exactly, but you know it’s right.” A song called “A Freak Like Me Needs Company,” for the eight-stilettoed Arachne and her Furies to sing near the end of the show, was apparently less right. “I thought, and still do, that it would be a hit,” says Bono. “A percussive eighties Paradise Garage dance piece with a fantastic hook. Julie was like, ‘No … ’ And I said, ‘Julie, isn’t this what you call a ten o’clock number?’ And she goes, ‘Who cares what time it is?’ ”

“A Freak Like Me” was replaced by a “post-Pixies Seattle backbeat” tune called “Deeply Furious,” which Bono says serves the story better, even if it has little hit potential. But hit potential is another thing Taymor doesn’t talk about. “Have we all become accountants?” she asks. Unfortunately, in a theatrical world of diminishing content and increasing opportunity to discuss it, many people have. They point out that with a running cost of perhaps $1 million a week, it would take two years at full capacity and Wicked-like average ticket prices for Spider-Man to earn back its investment. Cohl isn’t worried: People will come if the “vision is strong enough,” he says. In any case, he insists he wouldn’t want to be part of a “$28 million Spider-Man”—or any version, no matter how recoupable, that was not “Julie’s creation, something beyond the beyond. If it cost $100 million, I would do it.”

Which would seem to put an end to irrelevant speculation about anything other than the work itself. But like her beleaguered hero, Taymor finds herself having to face down a new menace each time the production seems to escape from the last one. Sometimes the difficulties are of her own creation; a ten-page Annie Leibovitz photo essay for Vogue nearly foundered over Taymor’s restrictions on how the show should be shot. Taymor admits she’s a very controlling director—“Controlling is what I do”—and while not everyone I spoke to saw that as a bad thing, no one disagreed. “She doesn’t want to know how hard it is to do it; she just wants you to do it,” says someone who has worked with her. “She does not come across in that situation as especially warm, but is that a requirement?”

And she is no more sparing, her colleagues point out, of herself. She lives, breathes, and dreams the show; her weight has dwindled to the point that an assistant sometimes gives her a Baggie of nuts and dried apples to bring to the theater. (At their daily dinner meetings, Cohl watches to make sure she eats.) But these symptoms of stress are not unique to the difficulties of Spider-Man, even though it is, she says, “the most complicated show I’ve ever done.” Thomas Schumacher, who as president of the Disney Theatrical Group had the odd but brilliant idea of hiring Taymor for The Lion King, recalls her collapsing with a gallbladder attack on the day the show arrived in Minneapolis for tryouts. Immediately after surgery she returned to the theater, where several seats were replaced with a Barcalounger for her recuperation. “She thought it was called a Bark-a-Lounger,” Schumacher says. “The place where she could bark.”

It is perhaps this undivertible drive that rattles those who don’t share it. The kinds of day-to-day missteps that any show endures (and that she tends to plow through) are, with Spider-Man, blown up to enormous proportions, not just because of the show’s budget and prominence in an otherwise small-scale season but because Taymor’s laserlike, slightly alien intensity—and perhaps her gender—make her an easy target. The New York Post’s theater columnist Michael Riedel, who so enjoys needling the show that he’s taken to calling himself its Green Goblin, recently described Taymor as a “pantaLOON” for the cropped trousers she sometimes wears, and for her supposedly spendthrift ways. Cohl says it isn’t true: She sticks to the budget. It’s just that the budget keeps changing.

Riedel has also been spinning drama from the “bloodcurdling” injuries sustained by two of the show’s performers—a story, however sensationalized for his readers, that gets at the dangers and opportunities bound up in the material. Aerial stunts in which actors zoom and battle directly over the heads of the audience are an obvious selling point for a show called Spider-Man; the mezzanine, where many of the liftoffs and landings take place, has been renamed the Flying Circle. It has to look dangerous or there’s no reason to bother, and yet it must be safe, which is why 30 hidden motors control the speed and height and trajectory of the movements. Maintaining the tension between these opposing ideas is crucial to Taymor: When someone shows me a jpeg of the motors, she flaps her hands in front of the computer screen. “Are you trying to take away the magic?” she cries.

Which may be why Riedel was able to make so much hay of the relatively minor incident in which one performer, Kevin Aubin, after being shot from the back of the stage to the front as if by a rubber band, broke his wrists at a group sales event. (Another performer broke a toe on the same maneuver; both he and Aubin are back in rehearsal.) Though Taymor attributes the accidents to “human error,” it will ultimately be up to the New York State Department of Labor to decide whether the show’s most perilous aerial sequences can proceed. In the meantime, Taymor flatly rejects Riedel’s suggestion that she is blithely pushing her “band of flying daredevils” past the bounds of safety. “I take safety very seriously,” she protests, and it’s true that the production plans to train an alternate to relieve the star, Reeve Carney, for a few performances a week. (The show already includes nine Spidey clones who do the most difficult stunts and sometimes serve as his backup dancers.) “But everyone has accidents in theater,” Taymor says. “It’s part of the world you’re in.”

If Riedel’s comments hurt her personally, she doesn’t let on in public. (She says she saves her crying for home.) But she is certainly mystified by the volume and tone of the show’s press coverage, even in the New York Times, which has devoted unusual front-page space to the show’s travails. She is not, after all, some newbie or interloper. She has been a major artist for years, having won a MacArthur “genius” grant as early as 1991, at a time when she was better known for her costumes and puppets than as a director. Over the years, she has refined and blended those interests into a new kind of job description, often taking control of elements that are more typically divvied among several artists. (On Spider-Man, she is director, co-writer of the book, mask designer, and, unofficially, much else.) The unity of vision that results is part of the reason her productions—not just The Lion King but also less commercial work like JuanDarién and Grendel, both composed by her companion, Elliot Goldenthal—have been almost universally praised. They are in the best sense spectacular, even as they feel handmade, and deliver great billows of emotion from little but imagery and movement, sound and surprise.

Such talents and ambition naturally led Taymor to make movies, including the Shakespeare adaptation Titus, starring Anthony Hopkins; the Kahlo biopic Frida, starring Salma Hayek; and the Beatles-catalogue musical Across the Universe—in which Bono plays a Ken Keseyian drug guru. Each is notable for its off-center sensibility. The violence in Titus is more operatic than exploitative, and the scenario of Across the Universe exposes the mechanics of its own cleverness in making the song cues inevitable. In fact, while her shows aspire to a movielike fluidity—“If people say it can only be done in a movie,” she crows, “that’s usually when I want to do it onstage”—her movies seem to deglamorize their filmic prerogatives in order to slow the viewer down. (The most brilliant moments of Frida, which cost only $11 million and won Goldenthal an Oscar for Best Original Score, take you into Kahlo’s paintings with deliberately artificial special effects.) Nevertheless, both kinds of projects, let alone her many opera productions, bear the stamp of a downtown artist with big theories and a powerful, if not always lucid, sense of conceptual purity.

And yet, despite all her indie and avant-garde bona fides, her embrace of mainstream efforts has been utterly without the irony and condescension that often accompany artists when they move from subsidized to commercial entertainment. (On the first day of rehearsal, she told the Spider-Man company she wanted to “do a piece that will translate not just to 13-year-old boys, which I think this will,” but also to “snooty-nosed” types and “I couldn’t be bothered with Broadway” geeks.) Nor, at almost 58, is she retrenching on any front. Spider-Man, had it not been delayed, was to be part of her big rollout December; her $20 million movie of The Tempest, starring Helen Mirren (in a gender switch) as Prospera, opens on December 10, and her production of The Magic Flute returns to the repertory at the Metropolitan Opera on December 21. The idea of treating such works, or the person who makes them, as if they were subject to cost-benefit analysis is completely bizarre to her. Art is not a product whose manufacture can be rationalized. Art is what you can’t even see until you make it.

With her kind of art in particular—visual, physical, as dense as dance—that can take a very long time. When, in early September, she leads a “stumble through” of the first act of Spider-Man in a bare rehearsal room, she has to narrate the action to make any sense of it for visitors. “And here is where he flies,” she says, as an actor poses like a kid in pajamas with his arms outstretched. “And here comes the Brooklyn Bridge with Mary Jane dangling from it”—the company, including Jennifer Damiano, who plays Mary Jane, stares at empty space. This clearly makes Taymor anxious; she flings her arms to indicate scenery flying away, and mouths every lyric faster than the actors can sing it. But it was she, after all, along with the playwright Glen Berger, who wrote the script that so nonchalantly calls for the most impossible things. “Decimated buildings on fire.” “He bounces off the walls and ceiling.” Did she know she could make such things happen when she wrote them? “Of course not,” she says. “What would be the fun of doing it if you already knew how?”

She uses the word fun a lot, which is jarring under the circumstances but makes sense if you take a step back. Who else gets to do what she does? And anyway, as she tells me one day in her loft on lower Broadway, over a cup of tea she forgets to drink, she’s been through much worse for her art.

“When she was 3, she told me she didn’t like the wallpaper in her room,” her mother, Betty, now 89, says. “And if you know Julie, you’d know it was typical.” The youngest of the three children of a gynecologist father and a Democratic Party committeewoman in Newton, Massachusetts, Taymor was precocious as an artist (her first-grade stick figures had nostrils) and as a believer in the priority of her own unusual tastes. She’d look through the newspaper to find things to do and then do them. Often they involved masks and performance. At the Boston Children’s Theatre when she was 8 or so, she was cast as Cinderella but called home saying she’d rather have been one of the stepsisters. In junior high, she made a statue of her boyfriend by wrapping him in papier-mâché. It could not, therefore, have come as a surprise to her parents that, when she was 15, she insisted on traveling to Sri Lanka—then Ceylon—and that at 16 she was off to Paris for a year on her own to study mime with Jacques Lecoq. “Other mothers would say to me, ‘Well, Betty, how can you let her go?’ ” her mother recalls. “But Julie’s not the kind of person you ‘let.’ ”

When making Frida, Taymor commented that most films on artists’ lives “drown in angst, grotesque behavior, and impossible suppositions on how and why the artist creates.” Nevertheless, when I ask her to look at her youth anthropologically, as a way of understanding how she became herself, she quickly sketches a thorough portrait of her environment if not her feelings. “I was a 12-year-old in the sixties,” she says. “I’m the little girl watching her parents take the older siblings through all the tumult of the time. My sister was a radical, my brother did the sixties thing. I was the observer. I called my parents by their first names. Traveled by myself into the city very young. Had a lot of freedom. I was treated as an adult.”

There is little affect to her voice; she might be describing someone else. But the story builds momentum without that. “Starting when I was 21,” she continues, “I spent four years in Indonesia and started my own Javanese-Balinese-Sundanese theater company called Teatr Loh; I didn’t know what the fuck I was doing. We created our own material. It was a different time. There was no fear. I sometimes say you have to put blinders on. If you have a vision and allow all of this peripheral stuff to get in the way, how will you get to the end of the bridge you’re building? But saying there was no fear doesn’t mean I was confident. I doubted myself every day! I cried more there than any time in my life. What am I doing in someone else’s culture? Creating a theater company, all of us living together, and I’m responsible, this Western kid? That was my trial by fire.”

She’s not even being metaphorical. Among many other disasters of her Teatr Loh years—police interrogations, floods, hepatitis, malaria, a terrible bus accident on Java that killed the driver of the other vehicle and left her with a still-visible scar on her chin—she at one point almost fell into an active volcano. She injured her leg severely in the process and was, naturally, operated on by a Vietnam vet with no anesthesia on the front porch of a beach bungalow built by Coca-Cola on sacred cremation ground. When I ask Betty Taymor how she could stand that her baby was enduring all this, she says, “I didn’t know about the malaria.”

So the gnat bites of the press have to be put in context. Taymor knows what it is like to be different from the people who usually do what she does, whether because she is younger, or female, or American, or a primarily visual artist (her sketches are sensational) in a field that too often prioritizes other modes of storytelling. The canonical directors of Broadway musicals—Abbott, Robbins, Fosse, Bennett, Prince—were either choreographers, writers, or producers first. More recently, their heirs have most often come as transfer students from “serious” drama. And though visual artists like Robert Wilson have on occasion established themselves as major figures in the avant-garde, even there, the visionary is usually the one with the psychological, political, or academic agenda. Taymor is absolutely sui generis, and in trying to bring her whole-world theatricality to one of its most vulgar marketplaces, she may be asking more of Broadway than it can bear. But if your reference point is The Lion King, all bets are off. Mounted at a cost of about $25 million in 1997, it has so far grossed $4.2 billion worldwide.

Brilliant anomalies make for good standards but bad examples. “There’s a feeling on Broadway and in musical theater in general that we need to cast the net wider for talent,” says Bono, who “grew up with musicals” (his father sang in several) and especially admires The Music Man. “That means you’re going to have some naïfs like myself and Edge turning up and wanting to do some impossible things. It’s a real recipe for disaster to meet someone else, like Julie, who enjoys the impossible. But she is not some dizzy artist who doesn’t give a shit about the bottom line. We aren’t either. People walking through those doors, in this recession, are going to see that the money’s been spent, and spent on them. Do you know what you call a person who when putting doves up their sleeves or a rabbit in the hat is still surprised when they come out? A magician. That is what she is.”

Still, she is an odd fit with Broadway’s schmoozers and hondlers, which is part of the reason some distrust her. One usually judicious theater veteran, who has worked with Taymor and admires her talent, calls her “the most selfish rich kid” he’s ever met: “The lack of humility and compassion is stunning.” But in several months of snooping around her, I never see that, nor any of the hysteria Riedel suggests is rampant in her rehearsals. Rather, what I see, and often, is that she is utterly unconcerned with, and in a childlike way even unaware of, how she comes across. She heads for her vision like a bloodhound. “I totally get this and dig it as a writer,” says Berger, who “auditioned” to work with Taymor on the book by dashing off a sample scene and has subsequently felt “a bit like Zelig” as he finds himself in meetings at Bono’s villa in Èze-sur-Mer. “It’s not really a question of being a control freak or a perfectionist, or being on an ego trip or having OCD. It’s simply that her vision is so specific that if you don’t get it right, it’s wrong. In fact it’s really wrong. Nailing it might come easily or it might take a lot of twiddling and finessing. But when it is right, everyone feels it, and then you can move on.”

If that’s a somewhat mechanistic view of theater, Taymor is probably the greatest machinist working. Her art has sometimes struck me as most effective when it is least “human.” The Lion King has personalities but no people, and even in her Shakespeare productions, the story is conveyed more through imagery than psychology. She seems, at least in public, to be almost without psychology as well; when I ask about feelings, she answers with systems, communities, history, folklore. She puts forth an idea of herself that is no less genuine for being a mask. She might say it is more genuine: Masks, she has noted, are catalysts for getting at a part of the personality that is otherwise invisible. Some of her actors, including the beautifully chiseled Reeve Carney, even look like masks. Which is not to say they are wooden. Carney, whom she cast as Ferdinand in The Tempest after seeing his self-titled rock band perform, is naturally vulnerable; in a recent tweet, he told fans he “got a good night’s sleep, repainted my living room, and haven’t even been condescended to once yet today! :)” Taymor has drawn that quality out of him for Peter Parker; she seems to get the performances she wants by involving her actors in rituals rather than introspection. But when I attempt to find out more about her process, I am stymied by her vagueness and their reluctance. With press leaks springing every day, there have been many stern lectures about not pulling corks.

Helen Mirren is under no such constraint. She says that Taymor just allowed her to play Prospera instinctively. “She assumed I could take care of the verbal and intellectual aspects myself. But you have to understand that Julie’s an amazingly driven, energetic woman. Egotistical in the correct way. The brilliant thing about her is that she also is incredibly girlie-girl, which I love because I’m a girlie-girl, too. When our husbands came at the same time to visit the set”—The Tempest was filmed mostly in Hawaii—“we independently of each other let out these ridiculously girlish squeals like 16-year-olds.”

It’s not just the long hair, the stripy sweaters, the colorful sneakers that make Taymor seem so youthful. She still maintains the air of a girl getting by in another culture, even if that culture is her own. What seems to rankle Riedel and chat-room snipers is the sense that such a creature is at liberty, unchaperoned, spending men’s money with no excuses. “I’ve got my foot on its neck,” Riedel recently wrote about the show, “and I’m having too much fun to take it off.” But Riedel’s feelings about Taymor turn out to be more complicated. He is, he says, a huge fan of her work. “I saw Lion King at an early preview in Minneapolis, went in very cynical, thinking Beauty and the Beast was horrible and Taymor is brilliant but weird. And I remember sitting there in the show-me pose with my hands across my chest, and when that giraffe came loping across the stage, my hands were down by my waist and my mouth was agog. Then the elephant came by and brushed my ear. By the end, people were standing on their chairs screaming, and I was right up there with them.”

Keep in mind that this is a man the cast of Spider-Man has taken to beating up in effigy, in the form of a ten-foot-tall inflatable villain otherwise called Bonesaw McGraw. “I’m not out to shoot her down,” Riedel insists. “I’m out to write a fun, juicy column. I cover a business—I’m not doing God’s work here. And they’re not doing God’s work either.”

Taymor might debate that. Though she’s “as happy as anyone” if a show makes money, her aims are not, God knows, commercial; they are not even primarily about personal artistic expression. Like the Indonesian performers she lived among so long ago, she seems to view art as an act of devotion, complete in itself, which is why the sides of sets never seen by the audience are finished as beautifully as the fronts, and why, as her mother puts it, “all those beads on the lions”—in The Lion King—“were hand-sewn. Did they really have to be?”

Well, yes: Costumes, like life, should look as good close up as far away. In fact, the point of Spider-Man—whose subtitle, Turn Off the Dark, was something Bono overheard a friend’s child say—is that the two perspectives are fused. “It’s that tug and pull,” Taymor says. “To live your everyday life and yet to have more required of you. Sure, you don’t want to have to think about slaves in India, aids in Africa, but once you have that newspaper in your hand, once you have knowledge, you are responsible. We want to say this in a musical because it is something very powerful to get across to young people. It’s not simplistic: It’s archetypal.”

“Tug and pull” might as well be her archetype. Among her upcoming projects, if she gets her way, are both a film adaptation of the Thomas Mann fable The Transposed Heads, which she directed onstage in 1986, and a stage version of Across the Universe, which she directed on film in 2007. Even her equanimity turns out to be the result of having kept herself in a productive state of tension for something like 40 years. Glen Berger says she hasn’t had a good night’s sleep in months—and that the show can’t afford for her to.

“I can handle a lot,” Taymor says. “The harrowing experiences I had very young allow me to step outside and look at the situation from somewhere else. You either have a good life with people you love or nothing’s worth anything. And look at my life! That I’m a woman living in America in the 21st century is already a huge plus. Elliot and I have been happily unmarried, we like to say, for 25 years”—they met through a friend who thought they’d like each other because their work was “equally grotesque.” “And though I didn’t have children in life, not by choice, I don’t know if I could do all these things I do and be a good mom. But these are our children”—she means her shows, which is apt enough, for they grow and grow and cost a fortune and no matter how well you raise them, who knows how they’ll turn out?

But that is actually not the question Taymor asks herself, even with Spider-Man, which may prove to be a great gift to audiences or a great write-off to investors (or both). What matters to her is how to do each day what she does. She’s the girl who knows what wallpaper she likes, and always has. “People say I’m driven,” she says, “but I don’t see myself as driven because I have nowhere to go. I’m there.”