Last week, not long after the Tony nominations were announced, I stopped by the end-of-semester recital of Tisch’s Graduate Musical Theatre Writing course. It’s taught by William Finn, the famously cantankerous writer-composer of Falsettos and The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee. I was seeking some uplift after a dispiriting season for American musicals—the kind that launches a thousand dirges from critics and pundits. (Hate writing ’em, hate reading ’em. This isn’t one. I hope.) The Tonys had simply italicized what everyone already knew: It’s been a bad year for bursting into song. Only two actual musicals are up for Best Score (the others are supplementary music for plays), and one of the Best Musical nominees has already closed in ignominy and penury. The dark horse for Best Score, Frank Wildhorn’s derided Bonnie and Clyde, shut its doors last fall, before the blood was dry on the Ford it rode in on.

In this doom-heavy atmosphere, Finn is a perfect tonic. Like a good song, he overspills his borders—he is just too much, which, for musical theater, means he’s just enough. Lavish in his pessimism on every subject except musical theater, he’s given to utterly sincere pronouncements like “All you can do is go about doing your work; it’s the only thing you can control in a miserable world.” Introducing his students, he digressed phlegmatically on the art of songwriting as he sees (and teaches) it. He compared the musical song to another all-American art form: the turducken. After trying, at length, to describe the gutting and cramming of three fowl into one unholy Poultry Trinity, Finn bailed out of his metaphor: “The point is, it’s very messy. The turducken is a very ugly food, but it has a lot of meat in a small space.”

But how many turducken do we see in the wild today? (It’s mostly just turkeys.) A broad survey of composers and producers reveals some consensus on root causes: Most agree that the book (the nonmusical script and story bone frame) is often woefully overlooked and that there’s a dearth of good book writers. (It’s notable that NBC’s hapless Smash follows the progress of a Broadway show with no discernible book and a book writer who can’t set aside her personal life long enough to finish.) “For years, we had people who were dedicated to writing books,” notes Finn. “Now you have to get them when they’re not working on plays. They’re doing us a favor—and when there’s a good line, we musicalize it, so they have to be willing to give up some of their best material.”

But if structure is a problem, so is raw inspiration. The Book of Mormon’s co-creator Bobby Lopez echoes many of his colleagues when he worries about “pressure from a producer to think small,” owing to the crushing expense of bringing a show to term: “Could you do it with fourteen people instead of 22? Can you get it down to five? Can you cut this crazy idea? But people want to see crazy ideas that work. Cut the crazy ideas before you give them a chance, and you’re limiting the art form.” Super-producer Scott Rudin decries that loss of spontaneity, too, and warns, “There are a lot of stories [told onstage] that do not need to be musicalized. The great musicals had to be musicals. Most of the musicals that get done now are not necessary. Not the way Clybourne Park is necessary.” Manhattan Theatre Club’s Mandy Greenfield backs Rudin up: “If you can answer the question ‘Does this need music?’ with anything other than a resounding yes, you shouldn’t develop that material.”

Smash composer Marc Shaiman, who co-wrote both the hit Hairspray and the fizzle Catch Me If You Can, expands on that. “The source material, Lord knows, is important. You have to have characters who naturally have that kind of something in them that makes it flow into a song with lyrics and music. With Hairspray, we were very lucky to have that. Catch Me was different, and the characters were not as inclined.” And when the material is not inclined, the spark of pure creation is too often replaced with the drudgery of Problem-Solving—which is when the corporate thinking kicks in and the show ends up crucified on a McKinsey Matrix. “I’m sick of the word ‘storytelling,’ ” says Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson’s composer-lyricist Michael Friedman, “which sometimes just means ‘Make this really clear and really dull.’ ”

Many of Finn’s students sounded quite promising, but few managed a full turducken. Of course, that takes time and practice and carnage. But I sensed in many of these younglings what I see in a lot of full-blown, not-quite-successful musicals: caution, consideration, delicacy. Symptoms of a frail marketplace of ideas. These kids wanted to Get It Right, but is that the job? Here was a roomful of writers who have all of their biggest messes ahead of them. Will they make them?

Four Musical-Theater Composers Explain What Makes a Perfect Song

As told to Rebecca Milzoff.

Musicals today—mindful of long odds, high costs, and the general precariousness of the form—are, I think, resisting their inner madness, and that’s a little like hating one’s own flesh. What basis besides madness can there possibly be for a form that’s as shapeless, idiosyncratic, and painstakingly artisanal as the novel yet as vastly collaborative and consensus-dependent as a Hollywood film? How do we reconcile these things? We do not. We embrace the schizoid totality of it. A true musical is the fissile power of internal contradiction gone critical. It’s the disciplined, rigorous release of madness from the molten core of the human soul, apportioned in meter, disciplined (barely) in song. Perhaps in our culture-wide search for the perfection solution to the Musical Problem, we’re missing opportunities to go a little more nuts. Embrace a bad idea or two: a singing barber-cannibal here, a tuneful prison romance there. Sometimes a “good” idea simply doesn’t sing, but a bad one does. We must save the calculations for scansion, and instead let something impractical romp across the countryside, laying waste. Overstuff our birds with feeling, with meaning. And let’s not get between ourselves and our madness—at least, not in the first draft. Lean times, we’re learning, call not for austerity but heroic overage. So today, the bad news, the barrel-bottom: but maybe? Tomorrow? A turducken in every pot.

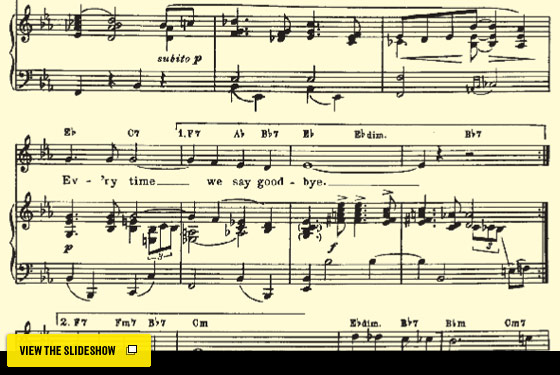

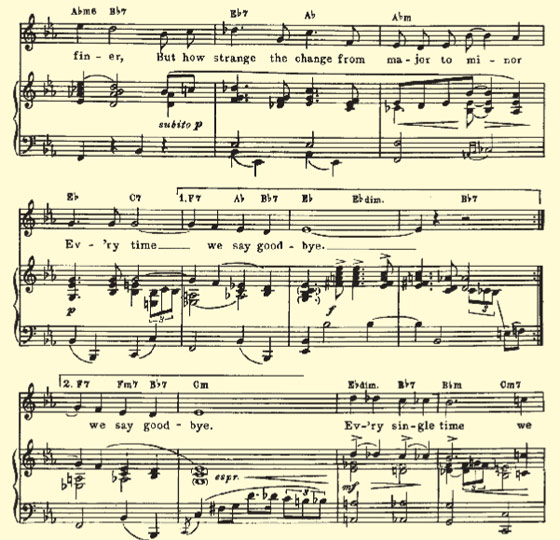

Cole Porter, “Ev’ry Time We Say Goodbye”

Chosen by Gabriel Kahane (February House)

“There’s no love song finer / but how strange the change from major to minor / ev’ry time we say goodbye.”

It could only be written by someone who does both music and lyrics. It’s in the final sixteen bars of the song, and “major to minor” is on the subdominant and the minor subdominant”the four to the minor four”and it’s a thriller. He’s coloring the lyric in an incredibly clever way and also a way that’s really emotionally satisfying, in addition to having gorgeous harmony and a great tune.

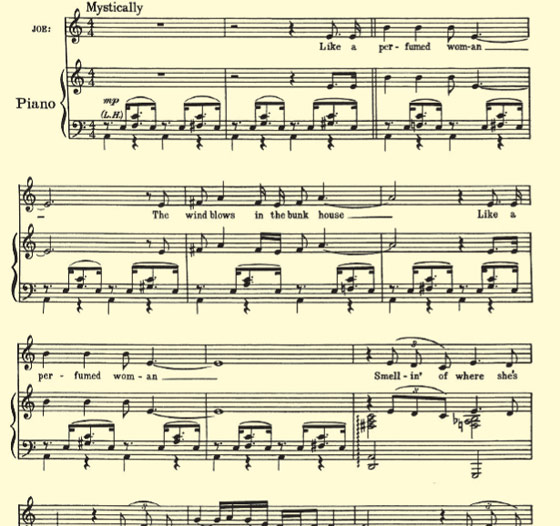

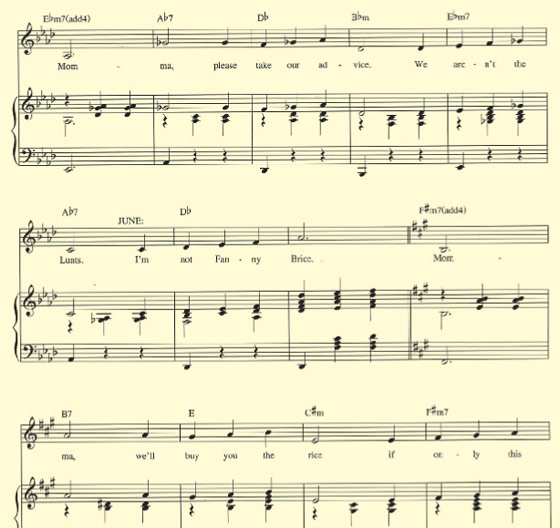

Stephen Sondheim, “If Momma Was Married” from Gypsy

Chosen by Marc Shaiman (Hairspray)

“Momma / please take our advice /

we aren’t the Lunts / I’m not Fanny Brice / Momma, we’ll buy you the rice /

if only this once you wouldn’t think twice.”

It’s so complicated but effortless. Look at all the inner rhymes there”“once” and “Lunts,” and all the “ice”s, and the wordplay of “once ” twice,” you have to wonder what comes first. As a lyricist, I know you often start with the last line and work backward. And the playfulness of the Jule Styne music, a melodic waltz, is perfectly matched.

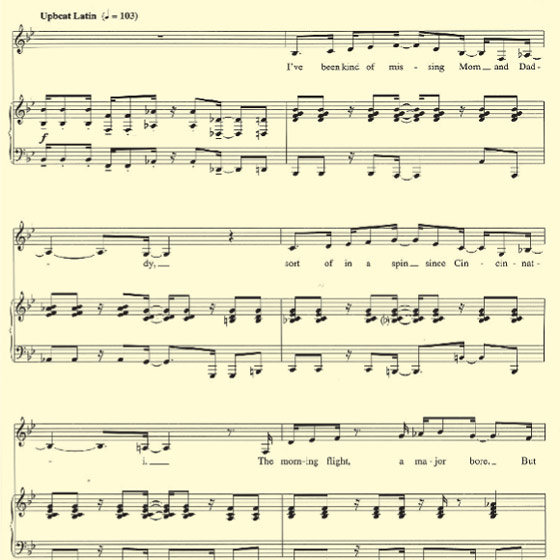

David Yazbek, “Here I Am” from Dirty Rotten Scoundrels

Chosen by Jason Robert Brown (The Last 5 Years)

“I’ve been kinda missing Mom and Daddy / sort of been a spin since Cincinnati / the morning flight, a major bore / but then they open the cabin door and / zut alors! Here I am.”

Yazbek has to introduce this person, Christine, whom we don’t really know, set up that we’re on the French Riviera, and establish that she’s a klutz. In five or six lines, and you can understand it. The music has weird harmonic shifts you don’t expect, the melody itself rising in a very satisfying way: “Mom and Daaaddy, Cincinnaaati.”