If you want to know why South Park’s Trey Parker and Matt Stone have made a Broadway musical called The Book of Mormon, which they describe as an “atheist love letter to religion,†it’s helpful to go back and watch—since you almost certainly haven’t seen it—Orgazmo, a small-budget 1997 film that Parker wrote, directed, and, with Stone, starred in (alongside porn star Ron Jeremy). It is, essentially, a morality tale about the seductions of Hollywood, made at a time when Parker and Stone, then in their mid-Âtwenties, had been in L.A. for a few years and were feeling frustrated.

In it, Parker plays Elder Joe Young, a wide-eyed Mormon missionary—after all, who is more wide-eyed than a Mormon missionary?—sent to Hollywood to spread the Word. But nobody’s listening, until he rings the bell of a porn director, interrupting his shoot. Young beats up the guards meant to toss him off the property and is offered the lead role in Orgazmo, the porno film within the film, for enough money that Young and his fiancée back in Utah could afford to get married in the big Mormon temple in Salt Lake City. The director is so determined to sign him that he says he’ll even call in a “stunt cock†when it comes to the actual sex.

Young goes home and prays to a plastic statue of Jesus for a sign of what he should do and gets an earthquake in response that decapitates his Jesus. But he does the movie anyway, and it’s a crossover success (cue the montage of big national magazine covers). The director offers Young much more money to do the sequel, then kidnaps his fiancée to keep him in line.

After the showdown, which includes the use of a ray gun one of the characters invents that gives its targets spontaneous orgasms, the end of the film has Young, his fiancée, and Stone’s character (whose tagline is “I don’t want to sound queer or nothing but …â€) standing outside the destroyed porn mansion and, instead of heading back to Utah, deciding to stay, declaring, “L.A. needs us. The world needs us. Heck … I think the whole universe needs us!†Then they pray. “Heavenly Father, may we serve you in the best way we know how. May our decisions be rash, may we do what’s right. And God bless us, every one.â€

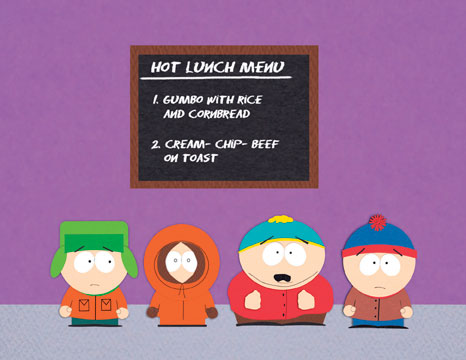

Their Hollywood prayers were certainly answered, thanks to four crudely drawn, foulmouthed, often-rash third-graders—Kyle, Stan, Cartman, and Kenny—who, by the end of every 22-minute South Park episode, try to do what’s right (well, except Cartman; he never does). The cartoon was picked up by Comedy Central while Parker and Stone were filming Orgazmo and premiered in August 1997. It was an immediate hit (cue the montage of big national magazine covers) and gave them the insolent fame of rock stars. They have a $75 million contract running through 2011 with Comedy Central, own multiple houses, fly private when they can. But most important, they get to wage their own scatological-lad jihad against the world’s unctuous phonies, from Al Gore to Bono to the MPAA star chamber that decides what ratings to give movies.

So they make fun of Scientology’s for-profit sci-fi theology in an episode that includes Tom Cruise refusing to come out of Stan’s closet. They have Paris Hilton come to the town of South Park to open a branch of her Stupid Spoiled Whore shop that culminates in a “whore-off†between her and a local S&M fetishist named “Mr. Slave†in which she inserts a pineapple inside herself (Mr. Slave, however, still manages to be the winner). They put the word shit in an episode 162 times. They depict the Prophet Muhammad shortly after the Danish Muslim-cartoon controversy (though on Comedy Central’s orders, he’s blurred out). They have Cartman exact revenge on an eighth-grade enemy by killing his parents, grinding them into chili, then feeding them back to him while much of the town watches. They hide a nuclear weapon inside Hillary Clinton’s privates (a “snukeâ€).

The power of their scorn is almost Old Testament: Everybody gets it. When they were up for an Oscar for the song “Blame Canada!†from their movie South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut, they showed up cross-dressed as Gwyneth Paltrow and Jennifer Lopez while, they say, tripping on acid. After they lost, they got up and just walked out.

“At this point, we’ve ripped on everyÂone,†says Stone, in a grubby lounge turned office at the Eugene O’Neill Theatre, shortly before The Book of Mormon began previews on February 24. He’s dressed in a black T-shirt and jeans and, post-lunch, is systematically eating an entire tin of Altoids. Caffeinated and jocky, with legs crossed, he pauses to pull out some dental floss, going so far as to unspool some before thinking better of flossing just then. Instead, he opens another tin of Altoids. “We’re kind of like the smoking section in high school. We’re immature, keep to ourselves. Like, Fuck those guys.â€

Today Parker is 41 and Stone 39—a little old to be immature. Stone is now married (the ceremony was performed by his friend the writer and blogger Andrew Sullivan, who got himself certified to do it) and has a 1-year-old son. Parker, who’s split from his Japanese wife (though when they were married, Norman Lear performed the ceremony), is now living with a woman with a 10-year-old son who wants to watch South Park. Parker can sometimes find the boy’s credulous reactions to what is clearly, to Parker, meant to be a joke alarming. As we were talking, their collaborator on Mormon, Robert Lopez, who co-wrote Avenue Q, was fretting over getting his 6-year-old in and out of a rehearsal before the number “Fuck You God†(a send up of The Lion King’s “Hakuna Matataâ€) came on.

Parker and Stone never thought they’d still be doing South Park at this mature age. “Really, not when we’re 50. That’d just be sad,†says Parker. In 2000, shortly after South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut had come out, Parker told Playboy that he was already stressed out about getting older: “I think in a lot of ways you have your best shit to say when you’re in your twenties. Not your most intelligent shit, but you’ve got your edge and you don’t give a fuck about anything, and that’s why it’s cool.†Which is as good an explanation as any as to where a lot of their ideas have always come from. But can it still? “You just get older, you start caring about things,†Parker said back then. “That’s gay, but …â€

When you strip away the satire, there’s as much equal-opportunity empathy as ridicule in their work.

The Book of Mormon is being sold partly on the idea that it’ll titillate—the show is, in many ways, just as offensive as your typical episode of South Park. And, if you happen to be a Mormon, certainly blasphemous. But it’s probably their gayest work yet, which means, by Parker’s definition, their most mature. It’s set in northern Uganda, where two missionaries arrive to baptize the plagued locals. Unfortunately, they’re equipped with just their Book of Mormon, the optimistic frontier sequel to the Bible, found by “all-American prophet†(as one of the catchy songs puts it) Joseph Smith in the 1840s buried near his home in upstate New York. In between the profanity, the show wants to ask: What happens when that all-American sequel proves not to be all that immediately relevant to a group of Africans ravaged by AIDS, poverty, and a local warlord who promotes forced clitoridectomies?

It’s also toe-tapping musical entertainment, allowing the audience to get swept up in the emotional power of a show tune, while also letting them smirk a bit. This, in and of itself, isn’t such a departure for the South Park boys. They’ve long played with the musical form in their work, and Stephen Sondheim liked the numbers in Bigger, Longer & Uncut so much that he wrote them a fan letter. But Mormon is their most sincere effort to write a musical. It’s their Broadway debut. And it’s a show that’s, more than anything, about giving a fuck. Sure, Mormon has man-frog sex—and Frodo, Hitler, Johnnie ÂCochran, and Yoda make appearances. But it’s strikingly life-affirming. Maybe the world needs a gospel according to Parker and Stone after all.

Meeting Parker and Stone can be a bit intimidating—you suspect, with good reason, that if you make any impression on them at all, they’ll make fun of you afterÂward. “They’re not snotty till you leave the room,†says composer Marc Shaiman, who worked with them on the songs for Bigger, Longer & Uncut. “From the beginning, everything they’ve ever done was to one-up each other and make each other laugh,†says Jennifer Howell, who worked with them for twelve years, starting as Parker’s assistant on Orgazmo. “They have that great guy humor that starts when you’re young: Make your friends laugh.â€

They came of age with a punk-rock ethos, in which conformity is the greatest sin, and extremeness the highest virtue. Parker, from the small mountain town of ÂConifer, Colorado (as the South Park theme goes, “Friendly faces everywhere / humble folks without temptationâ€), was a Âmusical-theater prodigy. Maniacally creative (he got a video camera in middle school and made little films constantly), he also starred as Danny in Grease during his senior year in high school. Stone came from suburban Littleton—not far from Columbine—played the drums, and was very good at math. After a detour through the Berklee College of ÂMusic, Parker ended up back at the University of Colorado, where he fell in with a group of friends who were more interested in Monty Python than Martin Scorsese. One of them was Stone. They acted in student films, riffing off each other and established themselves as the funniest boys in town.

“We were on our friend’s film shoot at an all-night diner,†remembers Jason McHugh, who went to college with them and worked on their early projects, including Orgazmo. “Trey was shooting and Matt was the dolly grip and they did dirty-grandpa jokes all night long. The more they did it, the funnier it got.â€

Somehow, each completed the other. Parker is far odder and more distracted (he kept texting while talking to me) and always half-submerged in his creativity. Stone, who wanted to be a “logician†when he grew up, is the more linear one. Parker is “just a big softy†with “a bit of anxiety about the world†who loves all sorts of music and musicals, says Toddy Walters, his ex-girlfriend, who also worked with him and Stone for a number of years. “I think Trey is supersensitive and imaginative, and sometimes people like that need someone to be their backbone and have their back.†They hash out ideas together, bidding up the absurdity, with Stone keeping a fix on the concept. But Parker is the writer and the musician. “Trey can be the genius boy in the bubble a bit, while Matt connects him to the real world,†says McHugh. “Matt Stone is like his name; he’s just really grounded.†Or, as Shaiman puts it, “Matt’s the wingman.†They seem to work perfectly in tandem.

Stone worked on Cannibal! The ÂMusical, the feature Parker made in college, based on an obsession he had with prospector Alfred Packer, who led a group of Utah miners to Colorado but was accused of killing and eating them on the way. “Trey had been engaged to this woman named Liane, and that fell apart and he was horribly depressed,†says McHugh, so he named Packer’s beloved but disloyal horse after her (the movie is “all based on Trey’s breakup,†says McHugh). The Sundance Film Festival didn’t respond to their submission of the film for consideration, but Parker told McHugh he had a “vision†that they needed to be there, so they rented a conference room in a hotel and put on their own screenings. MTV did a news segment on their guerrilla screening, and connections they made at the festival led them to the same agent and lawyer they have today. Producer Scott Rudin saw Cannibal! and gave Parker a script deal. (Rudin, Parker, and Stone still work together; he’s behind Mormon. McHugh, meanwhile, still works with Cannibal!, which has become a stage musical played around the world, and he’s planning to bring it back to New York.)

Parker and Stone’s careers finally took off when a video holiday card produced for a then–20th Century Fox executive—featuring a battle between Jesus and Santa Claus for Christmas dominance witnessed by the four future South Park boys—became a much-passed-around videocassette among Hollywood Âinsiders. (Yes, Kenny dies in the process, before Kringle and Christ are shown by the boys that it’s better to live and let live.) It got them the pilot on Comedy Central.

’When the scripts started coming in the weeks before South Park started, I thought, Can we get in trouble for this?†says Doug Herzog, the president of MTV Networks Entertainment Group who was running a struggling Comedy Central at the time. But “we were desperate for attention,†and Herzog knew that, if nothing else, the rudimentary cartoon, with its cussing kids and alien anal probes, would get that. As it turns out, the show became successful enough that Parker and Stone got a free pass to do almost whatever they wanted, even mocking Herzog. “They always say they write for themselves,†says South Park executive producer Anne Garefino, who was with the show from the beginning and is one of the producers of Mormon. “Because if you start to chase what other people think is funny, then you lose.â€

An episode is written, computer-Âanimated, recorded, rewritten, reedited, and broadcast all in a single week. Often the week includes an all-nighter. The quickness of the process is crucial: Parker and Stone decide on a target (say, High School Musical, or Inception, or Scientology), furiously research it, then figure out how to fit it into the tight little dramatic world of South Park. (In the Scientology episode, Stan is discovered to be the reincarnation of Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard.) Never mind that one of the characters from the show’s start, Chef, was voiced by Isaac Hayes, a devoted Scientologist, who quit in protest. The guys felt it was just time to send up Scientology.

The speed can also backfire: Earlier this year, they decided to make fun of Inception, and since only Stone had seen the film, they used as source material something from the Internet that turned out to be a parody of the movie. But when they write scripts with more lead time, between seasons, they think they just aren’t as good.

“Matt goes for the jugular on everything; he has no fear,†says Garefino. “And Trey takes that and makes it sweet.†ÂTheir roles can reverse as well. Howell, who Âtoday is senior vice-Âpresident of animation at 20th Century Fox Television, says that “Matt can sometimes be comforting, but not Trey. I remember once we were coming back from Vegas, and they’d rented a jet. I’m afraid of flying. There was this horrible turbulence; everybody was scared, it wasn’t just me. It happened to be Trey’s birthday. And he starts screaming, taunting God to kill us. ‘If you don’t kill us on my birthday, God, you’re a fucking pussy.’ I’m crying and sort of laughing … It’s the little boy in them; that little boy is very much alive in them. The idea of teasing and taunting and doing those little outrageous things.â€

As a result, a lot of people don’t take them seriously, dismissing them as the antic purveyors of potty-mouthed surliness. They were parodying themselves when they created Terrance and Phillip, the precision-farting Canadian comic duo who set off the war with Canada in Bigger, Longer & Uncut.

“Kind of my daily existence at South Park was being farted on,†Howell says. “I would leave the room and return and they would have farted all over my lunch. I’d come back and everyone would be laughing.†Once, early on, she sat between them on a plane, talking to Trey, and when she turned toward Matt, he’d positioned himself sideways, half standing up, so his butt was almost pressed against her face. And he let one rip. “It wasn’t like it was abusive, though some people might say it was,†she says. “I was like the little sister. If it wasn’t at my expense, it was at someone else’s. But they also deeply loved me and the people around them.â€

“Trey can be the genius boy in the bubble a bit, while Matt connects him to the real world.”

They’re older now and have long since stopped bragging about their drug use and sexual conquests in the press. They became very famous very young and took it as an invitation to say and do pretty much what they pleased. But they’re not flying to Vegas so often these days: Stone’s wife wants him home, for one thing. “I think they have mellowed out,†says Garefino. “I keep telling them I’m proud of the men they’ve become. They were harsher when they were younger.â€

The thrill of South Park is that it’ll make you squirm and at the same time often leave you with a sense that yes, that’s what I always felt, but nobody ever actually says that. It’s difficult to imagine much of the non–politically correct popular culture as we know it today, from Judd Apatow films to the nonstop viral parody videos on the Internet, without South Park. The show—and the movies, and this musical—is bratty yet confident in its adolescent wonder at the strangeness of the world and in its determination to keep screwing with people’s expectations and pieties. South Park is also very much in the tradition of Archie Bunker, in that it takes away the power of something horrible that some people believe simply by saying it out loud.

They refuse to give ideological comfort to anybody but a libertarian contrarian like Andrew Sullivan. “It’s the sanest thing on television,†he says. “Because it’s unsparing in its criticism of so much cant and crap that’s right in front of our eyes. And at the same time, there’s a core innocence.†South Park is hardly ever nihilistic, though it certainly pretends to be. “They never do anything to be controversial; they do things to be funny,†says Herzog. “Some people think Matt and Trey are Democrats, and some think they’re Republicans. But if you look at the show, there’s not anybody who remains unscathed.â€

Team America: World Police, their 2004 puppet film, was the ultimate example of their ecumenical scorn. It satirized both the heedless American flag-wavers and liberal celebrities trilling against the war on terror (in the form of a group called F.A.G.—the Film Actors Guild), all wrapped up in a musical spoof of a self-serious Jerry Bruckheimer action epic. “The biggest backlash we’ve ever had from anybody, from any religious organization—Mormons, from anybody—is liberals who saw Team America and were pissed off at us,†says Stone. “Our reaction was, ‘Fuck you.’ †On the other hand, they won an Emmy for an episode inspired by Terri Schiavo, in which the often-killed Kenny is kept alive in a persistent vegetative state, playing into Satan’s hands (Satan’s adviser tells him: “I will do what we always do: use the Republicans.â€) “There’s nothing partisan about them. Unless you count the snuke,†says Sullivan. “They’re totally equal-opportunity. And they’re always humane.â€

When you strip away the satire, there’s as much equal-opportunity empathy as ridicule in their work: “You watch Team America, and you see these gung ho types blow up half of Paris, and you still sort of like them,†says Sullivan. That film also has North Korean dictator Kim Jong Il acting like a lisping sociopathic Bond Âvillain and singing a touchingly mawkish solo called “I’m So Ronery.†And Satan, in Bigger, Longer & Uncut, is not just the terrifying lord of the underworld but a mopey co-dependent gay man abused by his inattentive lover, Saddam Hussein, who only wants to have sex with him from behind.

Satan’s not alone there in their troubled same-sex oeuvre: homosexuality is often used dramatically, to show a character’s troubled journey of self-discovery, from Stan’s learning to accept his gay dog Sparky to nightmarish Mr. Garrison, the closeted teacher, slowly coming to terms with himself and changing genders. One of the biggest laughs in Mormon is a tap-dancing number about self-repression—“Turn it off / like a light switchâ€â€”which centers on a closeted character trying to do just that.

But gayness is also used fetishistically, as a way to be as disgusting as possible. Sullivan, who is gay, says, “They’re no more homophobic than they have to be,†and he relishes the way the show revels in truly bizarre gay filth, like the cross-dressing undercover vice cop who is gangbanged in a frat house and then shown gleefully expelling the evidence.

“There is a strong through-line going through all of their work—I don’t know how to say it, homophobia, I guess,†says Toddy Walters. “Not that they’re homophobic. Either they think it’s really funny or [Parker] is really trying to process something.â€

After all these years, Stan and Kyle have only advanced to the fourth grade; Parker and Stone are famous, successful adults faced in some ways with the usual conundrums of answered prayers. They have the talent and the pull to accomplish a long-standing dream—a musical on Broadway—and by teaming up with ÂLopez and Rudin, they did it. “We wouldn’t have been working on it for six years if we weren’t trying to get the emotional payoff there,†says Stone. “It’s not an episode of South Park.â€

It’s not really about Mormonism, Âeither. In the play, the religion, as it’s depicted, seems to be mostly a symbol for them of other people’s drive for orderly niceness, their way of avoiding the incoherence of reality. Neither Parker nor Stone was raised religious, though they knew lots of Mormons growing up. “We all actually like Mormons,†says Parker. He and Stone are convinced, for example, that no Mormon who sees Mormon would be mad about it. This might be Ânaïve (and, from a marketing perspective, counterproductive).

For Parker, who loves to talk about ÂJoseph Campbell’s theories of the hero-journey, there’s no real difference between being a Mormon and being a Trekkie. “These people who get up every morning and put on their uniform and adhere to the rules of the Federation, to me that’s just sort of what a Mormon is, and I love that,†he says.

“In that decision to do that is something remarkable,†says Stone.

“To be a really good person,†says Parker.

“That decision to commit your life to certain principles and a certain narrative,†says Stone. “If I wrote a paper on that, I know I’d find inconsistencies.†But for a musical, they can draw whatever lessons they want.

The Book of Mormon is about wanting to find a story that works for you, one that makes you happy and, it is hoped, nice to other people. Maybe it’s a banal transcendence, but a transcendence nonetheless. “It’s about regaining your faith once you realize that all religious stories might not be the truth,†says Lopez. Parker and Stone appear to operate from a sort of good-Ânatured godlessness.

“My favorite episodes†of South Park, says Stone, are “when you’re like, ‘Is that my fucking lesson? Was that the lesson? I don’t know?’ We don’t know, that’s what’s crazy, we sometimes don’t even know.â€

And the lesson of The Book of Mormon is pretty simple: What’s really gay about it is that you walk away caring what happens to everybody onstage and you can’t get the songs out of your head.

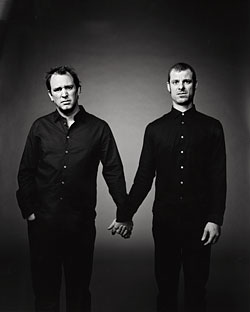

Orgazmo Stone, left, and Parker (who plays a Mormon porn star). Photo: The Everett Collection

South Park The South Park lower-schoolers: Kyle, Kenny, Cartman, and Stan. Photo: Courtesy of Comedy Central

South Park Mr. Garrison, the boys’ angry transsexual teacher. Photo: Courtesy of Comedy Central

South Park Saddam Hussein and his put-upon lover Satan. Photo: Courtesy of Comedy Central

South Park Mr. Hankey, the Christmas Poo. Photo: Courtesy of Comedy Central

South Park Paris Hilton, after she loses a “whore-off” to Mr. Slave on the show. Photo: Courtesy of Comedy Central

Team America: World Police Kim Jong Il, the lonely dictator. Photo: The Kobal Collection

Team America: World Police Lisa, a member of Team America. Photo: The Kobal Collection

Team America: World Police George Clooney, F.A.G. (Film Actors Guild) member. Photo: The Everett Collection

Team America: World Police Michael Moore, in front of Team America’s HQ. Photo: The Kobal Collection

The Book of Mormon Elder Price and Elder Cunningham head to Africa. Photo: Joan Marcus/Courtesy of BBBWay