It turns out there’s a real craft to building a dead horse you can believably kick around onstage. Sam Shepard, who recently had to bury his own horse, made it clear what he was looking for in the stage directions for his new one-man, one-horse play, Kicking a Dead Horse, which begins previews at the Public June 25 and stars Stephen Rea. “The dead horse should be as realistic as possible,” he writes, “with no attempt to stylize or cartoon it in any way. In fact, it should actually be a dead horse.”

So when the show premiered in Ireland, the Abbey Theatre dutifully located an actual already-dead horse (“With this PETA thing, you’ve got to be very careful,” Shepard says), made a cast from it, and used the horse’s real hide. “We were thinking it would have more realism,” says Shepard. “But when he kicked it, it reacted like a cardboard box or something. It flopped around. This one’s much heavier, has more resistance.”

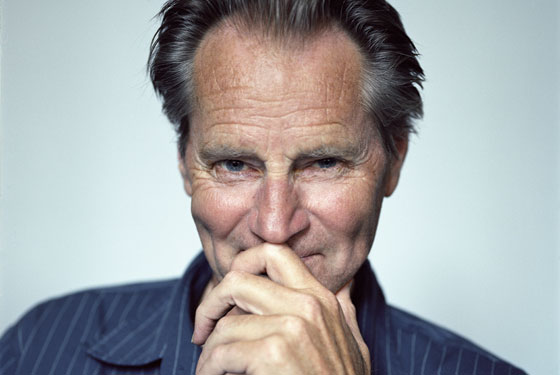

He points to a still-hideless taxidermy form (complete with articulated movable parts), which lolls cartoonishly in the middle of the Public’s grand, columned rehearsal space. Shepard sits at a table twenty feet away, looking not quite so countrified as you’d imagine: checked gray shirt tucked into neat jeans and a pair of stylish black sneakers. He almost seems to regret putting in that line about the horse—partly because of the technical issues and partly because it invites questions about what the horse “means,” and asking Shepard to “intellectualize” his work is like asking him to ride sidesaddle.

Still, it’s impossible to read Shepard’s new play—so different from the Western-family dramas he’s famous for—without coming to the conclusion that he is, at 64, mocking his own iconic image. Hobart Struther, a fiftysomething city man with vaguely country roots, has made a fortune plundering the honky-tonks of the interior for horse-filled landscape paintings bordering on kitsch, which he’s resold for millions thanks to a craze for Americana. Obsessed with “authenticity,” Struther leaves his family and sets off on an identity quest, only to have his horse choke on its oats and drop dead on the first day. Talking to himself while clumsily trying to bury the immovable horse, Struther ends up casting aside his Western implements one by one, along with notions of a mythology he now regards as “sentimental claptrap.”

This is written by a man who’s alternated between Hollywood film roles and black-box theaters, who’s ridden in rodeos only to come home to Jessica Lange (they split their time between here and Kentucky). Shepard will certainly not help you reach any conclusions about the play— “I think it takes all the life out of a piece of work”—but Public Theater head Oskar Eustis confidently says, “It’s the most personal play that Sam’s ever written: simultaneously really personal and existential, about the specific dilemmas of Sam’s age and experience, and also about America.”

It’s notable but not at all surprising that Shepard wrote this very American play on a commission from the Abbey, specifically for Rea. Europe is where Shepard first figured out how to write great plays. Having grown up in Duarte, California, he escaped his alcoholic father at 19 and landed on the Lower East Side. By the early seventies, he was writing experimental but “not long-lasting” work, romancing Patti Smith (she wrote a poem about his “playing cowboys”), and doing lots of drugs. “The Off–Off Broadway thing kind of lost its original zest,” he says. He’d heard London was still swinging, and off he went. There he met actors, like Rea, who were far removed from the earnest “Method” and excessive psychologizing of the Actors Studio, “far more eclectic in their gathering of stuff. They can sing and dance and carry on, they can do Brecht and all that stuff.” He directed a play for the first time—Geography of a Horse Dreamer, his own, at the Royal Court, starring Rea—and picked up the tools that, when you come down to it, make him as much a European playwright as an American one. In 1979, after he’d returned to the U.S., he won a Pulitzer for Buried Child.

Rea admits it took a while to warm up to the writer. “One didn’t approach him warily,” he says, “but you approached him, you know, with some respect for his self-containment.” But they drank lots of beer and whiskey and talked about Vietnam and Rea’s Northern Ireland, which was exploding at the time. They also bonded over a major idol, someone Rea had actually met: Samuel Beckett.

As Shepard ages, he looks more and more like Beckett—the squinting eyes, the deep furrows, the air of shrugging amusement. Kicking a Dead Horse could be superficially glossed as Endgame in the desert with an animal carcass instead of two clowns in garbage cans. “His mind, it’s awesome,” says Shepard. “I don’t want to keep beating a dead horse, but Beckett turned my head around about thinking about theater. It doesn’t have to be realistic, it doesn’t have to be buried in this cause and effect, it doesn’t have to be … dull.”

Reuniting with Rea and also with his old patron the Public (where he was last seen in 1994), Shepard thinks his plays are becoming even more interesting. He admires August: Osage County, but “I don’t want to do long family dramas. I’m just not interested in thrashing through those fields again.” He’s working on a new play for Rea, Ages of the Moon, about two old friends turned enemies. Sounds a little like True West or Simpatico, but he insists it’s a different breed. “I’m not interested in categorizing,” he says, “but [the new ones] seem to become themselves. They’re not calculated.”

His last play, The God of Hell, was unusually political; he claims the only time he voted was in 2004, mainly out of contempt for George W. Bush. For all of Bush’s blunders, Shepard seems most offended by his exploitation of cowboy tropes. “For George W. to be construed as a cowboy is about as far from the truth as you can possibly get. It’s ruined the reputation of Texas, which actually has more authenticity than many, many states—not in Dallas.” He’s also no fan of Hillary’s “riding around in trucks and talking about how she’s a blue-collar girl.”

But what really turns him off politics is the media’s phony typologies. Mention Obama’s “Appalachian problem,” and he says, “You find more racists in Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles than you would in West Virginia—I guaran-damn-tee it.” The red-blue divide is “media manipulation” at its worst. So are we all—Bush, Clinton, Americans, Sam Shepard—a little like Hobart Struther, saddled with the baggage of obsolete myths? Is that what the dead horse is about? He leans back and sighs loudly.

“Look, look, there’s a saying in the cowboy culture that a real cowboy has the horseshit on the outside of his boots.” Which is our cue to ride off into the sunset.