Theater people are always saying awful things about Arthur Laurents. One popular story has him expressing his displeasure over a rehearsal of the original West Side Story, for which he wrote the book, by pissing on the set. Another has him making a belated entrance at a panel discussion, draped in mink and announcing, “Behold, a living legend!”—to which Stephen Sondheim, also on the panel, supposedly retorted, “Wrong on both counts.” That these stories are almost certainly untrue (the former sounds more like Jerome Robbins; the latter like Leonard Bernstein) only emphasizes the degree to which Laurents’s actual antics attract them. In any case, he laughs them off—“What kind of asshole would say things like that?”—but doesn’t seem to mind the notoriety; as the name Dorothy Parker once validated a witticism, his name now authenticates an outrage.

That’s partly because, at 91, Laurents is one of the few left standing from the theater’s golden age of bad behavior. As well-known as he is for his writing, he is almost better known for his wronging. Straight people he believes to be gay have found themselves outed. Marriages he deems inconveniently convenient have been publicized as such. Even questions of paternity are not beyond his purview. And then, when he really gets going, beware. People who don’t conform to his narrative may find that they’re no longer in it. Especially when the subject is theater. On January 11, after the final performance of the revival of Gypsy he’d directed, he stood impassively during the curtain call as star Patti LuPone took a moment to acknowledge, in memoriam, both Jerome Robbins, who’d staged the 1959 original, and Jule Styne, who’d written the score. LuPone did so because Laurents, according to someone who was there, wouldn’t even “share applause with a dead man.”

That sharing problem was finessed six weeks later at the dress rehearsal for the current West Side Story revival. Robbins (whose 1957 billing credited him with choreographing, directing, and conceiving the show) was still dead, as was Bernstein, who’d written the score; Sondheim, the lyricist, was out of town, and the cast featured no stars. When the orchestra finished tuning up, Laurents, having revised his book and directed the production with the aim of reinventing it, stepped out from behind the curtain at the Palace—alone. The roar of the standing ovation seemed to blow him back at first; he is not unaware that many people, even those who don’t know him, think he’s “a mean, ornery son of a bitch,” as Larry Kramer put it in a rather loving piece he was asked to write for a 2002 tribute. (The piece was rejected.) But he quickly adjusted to being the toast of Broadway, an institution he often, and not behind its back, calls Chernobyl.

It was possible to believe, in that moment, that this self-styled Cassandra of the Rialto was the most adored man in theater. Admittedly, the invited audience was riddled with investors, friends of the cast, and others with an interest in the success of the $14 million revival. (It opens on Thursday.) Some were surely applauding the marvel of his vitality after a substantial life’s work: the books of those two classic musicals, among several others; more than a dozen plays, still being produced; a handful of directing successes, including the original Broadway production of La Cage aux Folles; and the screenplays for movies like Rope and The Way We Were. But there were also, no doubt, some who stood pro forma, fearing that if they didn’t, he would somehow, with his eagle eye for betrayal, hunt them down.

Once hunted, the kill is often swift. Kramer describes arguments with Laurents as “slam, bam, thank you ma’am” affairs that leave the victim reeling. (He can’t even recall what most of their fights were about.) But sometimes the kill is long, torturous—and in print. Several people volunteered to let me read (if not quote from) furious but beautifully phrased letters they’d received: the work, as one recipient put it, of a “vicious troublemaker.”

Anyone lacking such documentation can instead read Laurents’s score-settling 2000 memoir, Original Story By, or its just-published follow-up, Mainly on Directing. Billed as an inside look at the director’s role, the new book offers plenty of negative examples (Sam Mendes, Robert Wise, Harold Clurman) but very few positive ones (mostly Laurents himself). “Neophyte,” “shameless,” “Führer,” “disgusting,” “sentimental slop,” and “coked out of his head” are some of the gifts distributed to stingy producers, feckless collaborators, disloyal designers, and dim-witted actors. It isn’t ad hominem; Laurents seems less concerned with who you are than what you do. Praised on one page, Jerry Mitchell gets the lash on another. But Mendes, whose crime was directing the Bernadette Peters Gypsy in 2003, gets the electric chair throughout. Well, not quite: Laurents waits one whole sentence before insulting him.

Whether in print or in person, the barbs are well honed. (Truth, he writes, “doesn’t have to hurt, as those who don’t tell it profess to believe.”) The compliments are even sharper. (The producers of West Side Story, he tells me, “have been very good: They have not lived up to their reputations.”) A conversation with Laurents is dishy fun, as long as you aren’t worried about collateral damage. (An ex-friend: “He always wants to suck you into his malevolent opinions of someone; you have a choice to agree and feel hypocritical or disagree and get dropped.”) His mastery of the writer’s zoom lens for the unimprovable detail is always evident: the musical he and his partner, Tom Hatcher, took Laurents’s parents to see when they met—She Loves Me; the stack of “how to stop drinking” books on a table as martinis are served at eleven in the morning.

You hardly realize that while you were being distracted by such treats, the seducer has rotated his anecdotes 90 degrees; wherever they started, they now star him. And he knows exactly how to play the Robert Redford role of glamorous writer. His five years in the Army, he says, were partly spent “writing and drinking and screwing my head off” in a radio unit “created for me.” A story about his analysis ends up suggesting that Laurents himself is indirectly responsible for the removal of homosexuality from the American Psychiatric Association’s list of perversions.

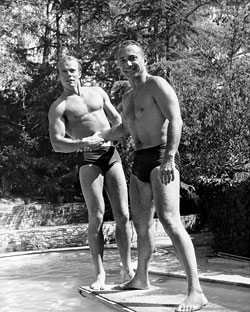

If provocation is Laurents’s default mode, his life experience long ago taught him the value, and perhaps the necessity, of unashamedness. Even in the fifties he was audacious enough to put Hatcher—a drop-dead hunk of a model turned actor he met selling clothes at a Beverly Hills men’s store—in some of his plays. But living openly as a gay man (and a lefty atheist Jew to boot) was only the start of it. The same principle applied to politics: You didn’t pull punches, you didn’t cower, you didn’t live a lie. In 1949, when the State Department declined to renew his passport on suspicion of seditious associations, he refused to disown his views; rather, according to Original Story By, he wrote a treatise describing them at such length and so idiosyncratically that the bureaucrats surrendered. He proved he couldn’t have been a member of any group.

Moral certainty may be inherently suspect, but that doesn’t mean it’s always misapplied. A stopped crock is right twice a day. For Laurents, the perfect excuse for his venom came in the convenient and recurring form of Robbins, perhaps the only theater legend with a more poisonous reputation. (Robbins was so disliked for his sadistic antics that the company of the musical Billion Dollar Baby watched silently as he backed up toward the orchestra pit—and fell in.) To condemn Robbins was not just a responsibility but a pleasure: He had named names before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1953. Yes, he believed he would be outed and blacklisted if he didn’t—but Laurents, who was blacklisted, didn’t buy that excuse. In her biography of the choreographer, Amanda Vaill relates the story of the two men sitting in Robbins’s apartment after the testimony; when Robbins muses that it would be years before he knew whether he’d done the right thing, Laurents says, “I can tell you right now, you were a shit.”

But the two men’s poisons seemed to neutralize each other, at least enough to allow them to collaborate, contentiously but brilliantly, on West Side Story and Gypsy. And it’s no accident that these are the two shows with which Laurents has made his late-inning Broadway comeback. For one thing, they’re the only shows he has any power over that are likely to be produced there; no one is clamoring to mount a megarevival of his 1945 debut drama, Home of the Brave. But West Side Story and Gypsy also represent Laurents’s last and best chance to rewrite theatrical history—now with better billing.

But how do you undo a legend? Laurents’s most recent revisiting of Gypsy—he also directed the 1974 revival with Angela Lansbury and the 1989 revival with Tyne Daly—largely involved adjustments at the margins. He made cuts, tweaked the ending, did excellent work with the actors, and, perhaps less successfully, replaced the live lamb with a Bunraku puppet. And even though the songs, to my ear, seemed madly rushed, as if to get past Styne’s (and Sondheim’s) contributions as quickly as possible, the critics raved: Laurents was hot again at 90. Still, when the possibility of reviving West Side Story arose, he wasn’t interested if the brief was merely to polish a trophy. Unless he could melt it down and make it new, he didn’t want to do it at all.

West Side Story, beloved as it is, poses daunting problems for any director. Even Robbins, in his 1980 revival, was unable to make the drama convincing. The problems generally begin with the dancing gangs, who tend to look about as violent as Mister Rogers. The only threat they might seem to pose is to your sock drawer. Meanwhile, why is fresh-off-the-boat Maria warbling about feeling so alarmingly charming? Is she, as Sondheim has often remarked in criticizing his own lyrics, performing in Noël Coward’s drawing room?

Laurents’s book is lean and muscular, moving the story at high speed while working several clever improvements on the Romeo and Juliet plot. Nevertheless, in approaching this revival, he began by rethinking his own contribution. Much of the dialogue, he decided, would now be in Spanish. “The idea was to equalize the gangs,” he explains, by allowing the Sharks, who are supposed to be from Puerto Rico, their own language. If this justification seems a bit dodgy—the Sharks still have less stage time than the Jets, and many people won’t understand what they’re saying—perhaps that’s because there’s more to the story.

It turns out to be a ghost story, aptly told one afternoon in the gloom of a tech rehearsal at the Palace. We are sitting in the mezzanine as the sound department tests sirens and the musicians warm up with snippets of the unforgettable Bernstein score: the cat’s-paw footfalls of the Prologue, the throbbing drums of the Mambo.

“I can tell you how it happened,” Laurents says eagerly. “For years, people were cruel to Tom as the less notable half of a couple. At least they lusted after him, so there was that. But eventually he stopped acting and became a mini-mogul”—buying, redeveloping, and selling property near a home they had in Quogue, on Long Island. “Over the years, he made a beautiful park there, twelve acres of ‘rooms’ that were once just big trees strangled with bittersweet. After he died, in October 2006”—of lung cancer, at 77—“I went to the park and sat on this one particular bench where we’d always talk. As I thought about how he wouldn’t be there when it burst into bloom next spring, I burst into tears and got out as fast as I could.

“Soon I decided to go on our usual ski trip because I thought it would be very good to be away from society and have a farewell ski. And then one day, I saw him on the slopes.”

Laurents shrugs. With his shiny eyes and fringe of hair, he looks like a garden gnome.

“Yes, literally. And then, when I came home to Quogue and walked into the park, he was there. He still is. I mean, he is and he isn’t simultaneously. We still talk, and yes, I actually speak. As for the answers, well, I’m well aware what his answers would be; I knew him so well. But there are also signs. One day, I found notes in his handwriting in a Spanish translation of West Side Story. That was a sign to do this production. These are not accidents.”

After 52 years together, Laurents understandably sees his partner’s hand in everything he does. Until Hatcher died, Laurents didn’t even have an ATM card. And it was Hatcher who convinced him to direct the LuPone Gypsy, so that Mendes’s version wouldn’t be the last one seen on Broadway in Laurents’s life. Part enforcer, part enabler, part keeper of the flame and of the grudges, Hatcher made Laurents’s writing life possible and somehow still would.

So West Side Story would be partly in Spanish; Lin-Manuel Miranda, who wrote the songs for In the Heights, was hired to provide the translation. Laurents next set about solving the other problems he’d identified. The gangs would have to be fiercer—“It’s the difference between a soft, balletic arm and a hard arm with a clenched fist,” he says. “Same move, different subtext.” The cast would be younger, and the Puerto Ricans, if not Puerto Rican, at least Hispanic. (This wasn’t always easy; Josefina Scaglione, the 21-year-old Argentine who plays Maria, was tracked down on YouTube.) The feeling of the set would be more desolate and, in one of the most powerful changes, so would the central relationship. In the lovers’ understanding that their dreams are futile in the face of larger forces, it is hard not to see Laurents’s own desolation over the loss of Hatcher, and also a reflection of his lifelong pattern of holding family and friends close and then finding them insufficient.

Not to mention collaborators. In order to effect these changes, Laurents had to make all sorts of cuts and alterations in work he did not control.

“It was Steve [Sondheim] and the Bernstein kids who wanted every note and every vamp and every word untouched,” he says. “What it comes down to is that even in this age of Obama, they basically don’t want change. The Bernstein estate was the worst. They’d say things like ‘Bars 75 through 81a have been omitted, and we want them back.’ But theater music is written for theater, and if you would like to stage it, you are welcome to come in and do so. They’re just pedants. Archivists.”

Laurents actually got his way fairly often, but Alexander Bernstein, responding for the composer’s heirs, would not take the bait. “We think that Arthur has done a superb job of reconceiving and directing the show,” he said. “He is an artist of convictions and has the courage to fight for them.”

“ ‘It’s a classic,’ they say,” says Laurents. “Well, so I hear. But the three previous revivals were all replicas, and all failed. That’s no accident. The original was about dancing and singing. This West Side Story is about what it was always meant to be about but wasn’t. This one”—he pauses as if issuing a challenge—“is all about love.”

“It’s when you’re miserable that he’s at his best,” says Stephen Sondheim. “If you’re happy or, especially, successful—watch out.”

Laurents maintains that Robbins’s credit for the conception of West Side Story was a case of overreaching. The gang element, he says, was his own idea, arising from news reports he’d been reading about Chicano riots in Los Angeles. Fifty years later, and ten years after Robbins’s death, the two men still seem to be enacting their Jacob-and-Esau battles. In the current revival, Robbins’s work takes the brunt of the changes. Yet it is Robbins’s estate, as Laurents admits, that has been “most accommodating.” For Robbins is that curious case of an artist who makes it into the pantheon without ever making it out of the doghouse. Laurents’s attacks on him, and some would say on his work, are in that sense innocuous: too little, too late. Robbins’s West Side Story will survive his revisions, even if they are improvements.

But Laurents’s attacks on those nearer by have done permanent damage. At his beach house in Quogue, photos of friends once lined a wall; as people fell into disfavor, their pictures were stashed in a large cigar box. “Oh, I’ve been cigar-boxed again!” became shorthand for Laurents’s rearrangements of his circle—but that, he protests, was 50 years ago. “Why are they still talking about it?”

Perhaps because it’s crowded in that box. He has lost many of his oldest friends—and not quietly. His public dismissals, epistolary upbraidings, and gleeful pans were like atomic bombs detonated on relationships already weakened by too many cycles of betrayal and rapprochement. Laurents doesn’t deny that he was usually the bomb-dropper; it’s the nature of the bombs he disputes. “What other people call mean,” he says, “I call telling the truth unguardedly.”

Laurents does not have, as most of us do, two truths: one in private and one for dress-up. Admirably, he has but one; the question is whether it’s true. “It’s only what he thinks,” says Kramer. “And he doesn’t say it to be truthful but to wound and to shock.” In any case, Laurents proceeds from a basic trust in his own convictions, let friends fall where they may. “If I worried about being thought well of, I’d have shot myself by now,” he says. “I guess I’m blocking or denying, but relationships I’ve had that have broken up—I forget them. You only have so much heart and time in life, and you waste your energy being angry, as I used to. And by the way, I’m just as honest with myself as I am with anyone else.”

Perhaps, in a touching way, even more so. No press or document I can find has ever let on, as some people told me, that the author of the play My Good Name was actually born Arthur Levine.

“True,” he says flatly—the only time I see him flinch. “I changed it to get a job. But that we don’t talk about.”

Not, it seems, because the change itself is embarrassing to a man who sees his standards of honesty as fundamental and exacting. (Many Jews, especially in the arts, have reimagined their names: Robbins was born Rabinowitz.) Rather, his reluctance seems more primal, recalling to memory the virulent anti-Semitism of his Brooklyn youth: the drive-by hooligans shouting out “sheeny” as he stood at a trolley stop, shaded by a tree, in his first pair of long pants. But the memory stopped there. The teary past, he says, doesn’t interest him; even during his time in analysis, he rarely brought up his childhood, despite such ripe figures as an embracing father, a difficult mother, and a sickly sister. “I don’t want to know that maybe there’s something really askew with me,” he says. “It makes it easier to live, I’ll tell you that.”

Indeed, in our conversations, Laurents seemed to be steering a narrow mountain road between two overwhelming abysses: the pit of sadness on one side, and the sea of vitriol on the other. As the sadness, with its odor of sentimentality, repulsed him, so the vitriol attracted him; the combination made me wonder how he ever stayed on track—and explained why so many passengers had bolted.

Sondheim held on until a few years ago, when yet another Laurents jab appeared in an article. Sondheim declined to “stir up any goblins” by discussing specifics but said, “It’s not that I don’t talk to him—we have a working relationship. But the friendship is kaput, and we once were really close. I was the last long-term friend of his to say ‘enough already.’ The best part of our relationship was wonderful. He was a joy to write with. It was only when rehearsals started that the trouble began, especially if another director was involved. And he was always a great foul-weather friend: comforting, smart, a good guidance counselor. When I had my first serious love affair and it broke up, I was destroyed, and Arthur was one of the two people who steered me through the shoals. It’s when you’re miserable that he’s at his best. If you’re happy or, especially, successful—watch out. Arthur is the master of the imagined slight. I had the temerity to question some of the things he did to Gypsy when it transferred from City Center to Broadway—oy, was that a mistake. The screaming hasn’t stopped since.”

Most of Laurents’s other ex-friends plead the Fifth. Ellen Violett, a television writer, actually gasped when I mentioned Laurents’s name on the phone. She and her partner, the artist Mary Thomas, had palled around with Laurents and Hatcher for decades until Laurents did whatever he did; another ex-friend told me it involved a vicious dinner-party comment about Thomas’s career. In any case, they haven’t spoken since 2001, not even when Hatcher died. “I’m glad about his success, sad about Tom, and don’t wish to say one more word about it,” said Violett. Thomas wouldn’t speak at all.

Even the theater composer Mary Rodgers Guettel, no slouch in the candor department, went silent for a moment when asked about the long friendship she and her husband, Hank, shared with Laurents. Eventually, she dictated this statement for the record: “Call me back when he’s dead.”

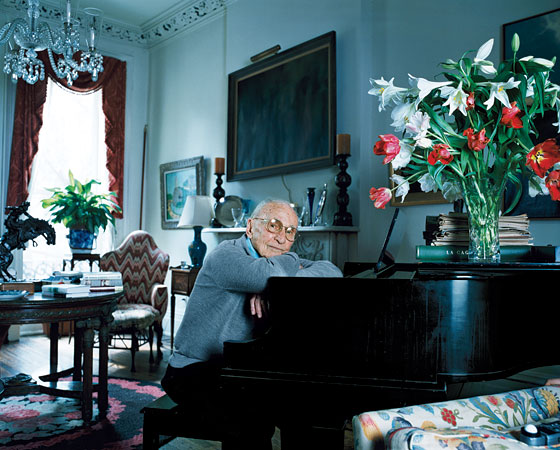

That may take a while. Climbing to the mezzanine at the Palace and, later, moving about his 1852 West Village townhouse—where the walls are covered with art and the tables are encrusted with brass and crystal tchotchkes—Laurents looks preposterously fit. David Saint, his associate director on West Side Story, calls him a mountain goat. Sure enough, he had recently returned from a ski vacation in Megève with the director Harold Prince, one of his few old friends not in the cigar box. He has made little accommodation to age, and even while tinkering daily at the Palace was involved in casting a new play, called New Year’s Eve, which will begin rehearsals at the George Street Playhouse, in New Brunswick, New Jersey, two days before West Side Story opens. Another, called Come Back, Come Back, Wherever You Are, is waiting in the laptop; one glance at the screen saver—a photo of Laurents and Hatcher, looking happy and studly by a Hollywood pool in 1962—tells you what the play is about.

But everything is about that now. “Sometimes I just think my heart will break,” Laurents says. “And then I just get through it. I try to do what I know he would want. It’s why I’ve become so spiritual lately.”

He pauses to appreciate the imaginary gagging sounds of the theater community. “I know you are saying, ‘Arthur Laurents, spiritual?’ And it’s true, this is the kind of thing I would have scoffed at in the past. But loss gives you perspective on what’s important. I used to be upset when productions I thought were inferior got raves. Now, I think, like Rose, ‘That’s show business.’ I don’t have any need to respond anymore. I do care that the theater isn’t better. Where is the emotion? Sentimentality is an expensive substitute for emotion, but look at what gets attention on Broadway. Take a recent hit and an avant-garde cause célèbre: One is about ‘I’m going back home’ and one is about ‘I’m going back to mama.’ ” He seems to be describing In the Heights and Passing Strange but catches himself before driving off that cliff.

“The theater means a good deal less to me. I care about my few—and they are few—friends. I care about love.” Seeing my eyebrows lift, he adds, “Do you think I’m holding out on you? I’m not. This is who I am.”

Certainly, the young company of West Side Story adores him; they treat him as an embracing father—“or grandfather, or great-grandfather,” Saint says. But this lovable Laurents is hard to square with the one on display in Mainly on Directing. Despite what Laurents has described as good-faith efforts to strip the book of viciousness, you could hardly blame Sam Mendes if he felt that the strip job didn’t go far enough. Mendes, who staged several successful musicals at London’s Donmar Warehouse, which he ran until 2002, is repeatedly called unfit for Broadway because his work on Gypsy proved he doesn’t have “the musical in his bones.” The epithet is never defined, but that’s the point. “You either got it or you ain’t,” Laurents concludes, quoting Sondheim’s lyric for “Rose’s Turn.” And “he didn’t got it.”

Mendes, who may originally have incurred Laurents’s wrath by declining to produce two of his plays at the Donmar, said in an e-mail message: “I do not wish to comment on Arthur Laurents, despite the many opportunities recently afforded me.” Perhaps he prefers the box office to comment for him; Mendes’s Gypsy was seen by 100,000 more people than saw Laurents’s and grossed $6 million more.

But from a theater-lover’s perspective, the key facts are that both productions had wonderful moments and neither recouped its investment. It’s all musical chairs on a sinking ship. When the tune stops, who cares who’s left enthroned at the bottom of the ocean?

Laurents has been writing for almost 70 years. Home of the Brave appeared in an anthology of great plays of the forties alongside The Skin of Our Teeth and All My Sons. But as Wilder and Miller—and Williams and Inge and, later, Albee and Mamet—became part of the canon, Laurents was left holding only West Side Story and Gypsy, collaborations in which he’d taken a back seat to Robbins or Bernstein or Styne, if not Sondheim. “So now he’s trying to bring the spotlight back to his own work by minimizing the contributions of the others,” says one ex-friend. “He’s Rose at the climax of Gypsy, bellowing ‘Someone tell me, when is it my turn?’ ”

According to this interpretation, the accident of longevity has given Laurents a platform on which to portray himself as the primary author and sole savior of works that were severely limited by the conventions of their era. In other words, he’s rewriting the history of the American musical theater—and saying, with Rose, “this time for me.”

Laurents is not impressed by the theory. “I don’t care about what prize I get or whether I’m in somebody’s collected works. I don’t worry about the past or think about posterity. I live in the now. Some of those writers—Williams, Inge—when they had failures, they went to pieces. But I went, ‘Okay, here’s another.’ Which is good for you. People are quite disbelieving about all of this, but that’s the way I am. I get angry; I get over it. Apparently others don’t.”

Is this the equanimity of the deranged or of the only honest person in the thin-skinned world of Chernobyl? Either way, it’s equanimity. Many old men become incontinent; perhaps Laurents is living in reverse. David Saint, who describes Laurents as his best friend, and who has been living in the West Village townhouse with him during West Side Story rehearsals, says he actually sees Laurents button his lip from time to time. But he’s not sure that’s an improvement.

“When I was first offered a script of Arthur’s”—Saint is the artistic director at George Street, which has produced eight of Laurents’s plays—“everyone warned me he eats directors for breakfast. And it took me a few years to get used to the fact that he could come see a play and, literally as he’s coming down the aisle, say, ‘David, it’s a piece of shit.’ You sort of have to wipe that off your face, but then, after you talk to him about it awhile, you see that he understood why you did it, he doesn’t think you’re an idiot, and he acknowledges the positive parts of it. Which is the opposite of what most people do: say they love something and then, over time, let you know they didn’t. Is that better?”

Indeed, his ex-friends and fuming colleagues admit that no one ever offered more incisive feedback on their work. If they miss it, too bad; he’s moved on. As beautifully psychological as the book of Gypsy is, Laurents isn’t interested in reviewing his own behavior. He’s only interested in continuing to have behavior. “When he gets the mail every day, he opens every letter and answers immediately,” Saint says. “He opens every bill and pays it. He can’t put anything off. When I try to be diplomatic, he says to me, ‘David, if you just get it out, it’s much better, because if you get something out, it’s gone.’ ”

And look how far being undiplomatic has got him: if not all the way to the pantheon, at least to its suburbs. What must be galling is to have seen those who were hypocrites, like Robbins, or who lived (in his view) less-honest lives, step so easily through gates kept shut against him, as if he really were every disreputable thing the world of his youth tried to peg him as: sheeny, commie, dirty fag.

“I don’t think anger is a very deep emotion,” he says. “I think pain is.” He is talking about West Side Story but the thought applies to Gypsy as well. One is about the pain of love in a world of hate, the other about the pain of not being noticed. Whether they are both in that sense autobiographical is something one doesn’t ask Arthur Laurents—let alone Arthur Levine.