Like a backwoods Mary Poppins, Dolly Parton has just materialized at a recording studio in Manhattan and is distributing MoonPies and GooGoos—confections she brought with her on the bus from Nashville. She is greeting some of her collaborators on the musical 9 to 5, asking after their health and their people. Unlike a lot of celebrities, she seems to relish actual contact with humanity; she grew up so deep in the country that she’s “always tickled to death to see anybody!” To the strangers in the room, she offers a hand and a howdy to break the ice. The men, especially, need it. She is so small, and so large, and so unusual, that any way of reaching into her space uninvited seems like manhandling. It’s as if she were a prehistoric bird or the queen of England, with the additional concern that you might accidentally deflate something. I’ve heard of her grabbing a guy’s head and pushing it straight into her cleavage, just to put him at ease. (Can this possibly work?) Or she’ll say, “Aw, honey, don’t be nervous. I’m just a lady like everyone else.”

A lady, definitely. Like everyone else? Maybe in her unpretentious, self-mocking demeanor. But that has always been misleading, both in terms of the depth of her artistry and the artistry of her surface. First heard on the radio at age 11, she’d hardly have spent the next 52 years amplifying her outré image (and repeatedly entrusting herself to plastic surgeons) just to be ordinary. No, she is, as she says, “a poor candidate for espionage”: proudly alien-looking, beautiful and strange. She’s attired and made up, as always, to emphasize this: black tights with gold filigree; black suede stiletto boots; a black plunge-neck jacket with gold zippers, grommets, and drawstrings; bubblegum-pink acrylic nails about two inches long; and a tall white-blonde wig kept aloft by assorted trusses and diverters. Over the next few weeks, I will see her in many getups like this (she has hundreds custom-made each year, at a cost of several million)—all tight, all sparkly, all designed to focus attention on a woman who would otherwise be just a tiny 63-year-old: five foot one, with slim legs, pretty eyes, a waist no bigger than a vase, and that bust flowering out of it.

Being bountiful is clearly a top priority. She wants to provide everything people want from her at all times. Within that, she’s smart enough to find ways to ensure she gets what she wants, too. Making a stage musical of 9 to 5 was not her idea; it came from Showtime Entertainment president Robert Greenblatt, who’d bought the rights to the 1980 film about three underpaid women who take crazy revenge on their pig of a boss. But the opportunity to create a line extension for her worldwide brand, combined with the creative challenge of writing songs for Broadway, piqued Dolly’s interest. “I was just dumb enough to say yes,” she says—but not to sign on as a producer in an industry she knows nothing about. She’s fearless, not reckless.

And so she is with her time. While devoting several years to the musical, she has maintained her regular and profitable schedule of recording and touring. (Her 2007 and 2008 concert tours grossed more than $60 million—and she owns these operations outright.) Her daily schedule gives fair time to each of the many activities it includes but not a moment more, and even so, she is up half the night, thinking and writing and consulting with God. That attention to self-management applies at every scale; even now, in the recording studio, when a photographer starts snapping, she shines for the lens and all but stage-manages the setups. “Do you want some in the booth? Will the glare be too much? Some of me with Stephanie or with all the musicians?” But then she warns: “After you get the shots you need, we’ll run you outta here”—with a giddy laugh, as if being run outta here is the most fun anyone could have.

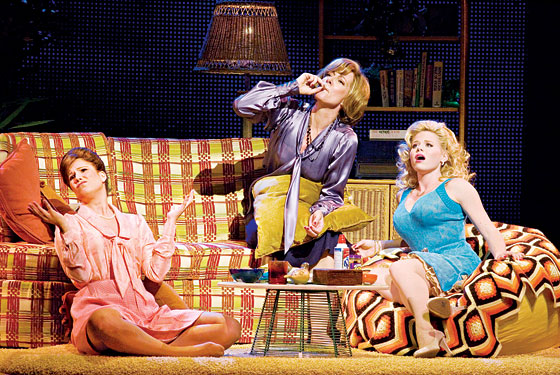

Stephanie is Stephanie J. Block, one of the stars of the show, which opens on Broadway next week. She plays Jane Fonda’s role: the dumped wife who has never had a job. (Allison Janney plays the Lily Tomlin role—the super-competent manager always passed up for promotion; Megan Hilty plays the bombshell who’s mistaken for a bimbo—in other words, Dolly.) And though Block has spent a lot of time around Dolly during the show’s development, today she looks awestruck anyway: She is recording her first solo album, and Dolly has agreed to sing backup on one track. As if that weren’t enough, the track is a cover of “I Will Always Love You,” probably the most famous of Dolly’s songs and certainly the most lucrative. At a time in Dolly’s career when she could still have used the boost and the cash, Elvis offered to record it—but only if she sold him half the rights. With precocious confidence in the value of her work, she refused. The lyric “We both know that I am not what you need” must have seemed especially painful under the circumstances, but as a result of that decision she has made millions of dollars in royalties on the song’s many incarnations, none of which improved on her 1974 original.

And yet here she is in the isolation booth, trying to improve on it herself. As the engineers play back Block’s prerecorded track, along with the musicians’, she starts to improvise harmonies, calculating when to join Block’s line and when to cut out, when to match rhythms and when to counter them. You can almost sense her internal computer processing the choices: Higher or lower? Fill the pause or leave it? Whisper or wail? She keeps trying variations on her riffs, which she calls “my little curls”—an astonishing armamentarium of baroquely detailed turns, runs, melismas, appoggiaturas, and corkscrew roulades worthy of Joan Sutherland, except not so much performed as shed. You’d think you could pick them out of the carpet when she was done.

But she doesn’t ever seem to be done. She waves her fingers every few seconds to signal she wants to start again. She madly fidgets with the dials on her monitor as if it were a mandolin, trying to hear what she wants to hear. Her eyes are mostly closed. “I just gotta find the flow to it.” If she’s a tiny bit shy of a high note, she sucks on a Halls lozenge and tries it over. “It’s way up there,” she mutters. She is always dissatisfied. When the crew and Stephanie firmly believe they have more than enough good takes, she says, almost plaintively, “I’ll be happy to do it again.”

“But that one was gorgeous!” Block shouts.

“Let me find a gorgeouser one,” Dolly grouses. And sure enough, when allowed to sing the whole song through (“I’m not the kind that does things in bits and pieces”), she makes it all fall together: the madly fluttering vibrato, the eerie Sprechstimme, the piercing holler, the unanswerable woe.

By now Block is crying. It had not been her intention to ask Dolly to record: “I didn’t want to be one of the thousands of people who want things from her.” But colleagues convinced her and, after spending hours one day crafting the perfect e-mail, she woke up the next morning to an answer from Dolly saying “Of course” and even suggesting the song. “She said, ‘Perhaps you’ve heard it; it was the theme from The Bodyguard,’ ’’ Block recalls. “I don’t know whether it was humility or humor!”

It’s not clear that, for Dolly, the two are different. In any case, such contradictions are central to her character and, not incidentally, to her fame. They have made her tabloid fodder for most of her career: the wholesome advocate of family togetherness with no children, an invisible husband, and a ubiquitous “best friend.” The traditional country singer who scandalized Nashville by branching out into godforsaken pop. The woman of faith who eschews organized religion and modeled her looks on local prostitutes. The good-time gal who amassed a diversified entertainment empire that rakes in hundreds of millions a year.

She happily explains all of these, if asked: Her husband of 42 years, Carl Dean, hates publicity, but they are a happy couple who make room for each other’s needs. They wanted children but are now glad they couldn’t have any, because look at what kids get into! (They did, however, help raise many of her younger siblings.) The best friend, Judy Ogle, has basically been her sidekick and archivist since they met at age 7. Country music is her base, but a natural curiosity keeps her looking for new territory. She talks to God, but not in church, and judges no one, least of all about sex. As for the income: It takes a lot of money to look this cheap. “Now what else do you want to know?” she asks cheerfully. “I’ll decide whether to answer.”

But the explanations, most of them familiar from years of use, don’t make anything less mysterious. They don’t touch on the question of how she created this Whitmanesque character, admired well beyond her natural precincts as one of the great vernacular American songwriters, from a dirt-poor, hyperactive mountain girl in a family of twelve, whose sharecropper father couldn’t read, whose mother always had “one on her and one in her,” and whose first song, written at age 5, was called “Life Doesn’t Mean Much to Me.”

Everyone says that to get to know Dolly, you have to see where she came from. So one day at the end of March, in time for the annual reopening of Dollywood, her theme park in the foothills of the Smoky Mountains, I fly to Knoxville, Tennessee, and drive an hour to Pigeon Forge, which sounds like the name of a hillbilly hamlet where you’d sleep in a tree and expect to eat squirrel. No such luck. The town amounts to a several-mile-long strip of family-fun venues, if your family enjoys waiting in lines to squeeze into bumper cars and rear-end other families. As for food, well, the hotel that Dolly’s people tell me is the finest in the area—and it does have nice rooms along with its year-round Christmas decorations and hourly glockenspiel concerts—tops off its complimentary breakfast of things-robed-in-gravy with a glistening pile of Krispy Kreme doughnuts.

Though Dollywood is much more interesting than the surrounding town, a visit there will not help you achieve Dolly’s waist size. Steve Summers, Dolly’s creative director, tries to make me eat fried baloney at an establishment called Aunt Granny’s, where everything seems to be fried, even the waffles. My stabs at resistance are met with suspicion. “I eat your sushi when I’m in New York,” says Summers. Though I have ground my supply of Lipitor into a paste and swabbed it over myself as a shield against ambient cholesterol, I feel my defenses beginning to crack.

Dollywood (and Dolly) will do that. They give sophistication a bad odor. The theme park, which she owns with a regional entertainment company and which is now in its 24th season, is surprisingly untacky. I suppose I expected a vanity village, or at least a straightforward exploitation of the Dolly brand, with cleavage rides and a Burt Reynolds Toupee Toss. But except for Chasing Rainbows—a jaw-dropping museum of her origins and career—and the signature butterflies used everywhere as decoration, the place isn’t really about Dolly at all. It’s about what she loves and cares about or thinks the park’s 2.8 million annual visitors will enjoy. That means roller coasters and thrill rides (which she’s never been on; she gets motion sickness) along with a strong overlay of Smoky Mountain culture: wainwrights, luthiers, smithies, potters, gospelers, bluegrass pickers, guitarists, and a chapel.

“I’m creating jobs. I’m like Obama. O-Dolly and Obama!”

My plan is to tail her closely as she descends on all this and makes her rounds the day before the opening. Great, except that by noon I’m exhausted. Granted, I don’t have a retinue, but then hers—Summers, Ogle, assorted assistants, and security—can hardly keep up with her either. Summers, who started at the park as a performer, and whom Dolly sent to F.I.T. for additional training so he could design her wardrobe, reels off the part of the schedule that Dolly already completed before I joined them: a 5 a.m. interview for a syndicated news show. A photo shoot for Dolly Parton’s Dixie Stampede—the chain of three dinner theaters she owns with the Dollywood people. A voice-over at a recording studio. A photo shoot for the Penguin Players (a live-action show for the Imagination Library, her early-childhood reading initiative). Recording a segment of a documentary about the itinerant preacher who delivered her and was paid with a bag of cornmeal. Taping a “pick up the trash” public-service announcement. Accepting a DAR good-citizenship award. Filming two songs for the Imagination Library. She will go on this way a few more hours. She will wear fifteen outfits. And this is typical of the twenty or so days a year she’s at Dollywood.

It soon becomes clear that while Dollywood may be a good place to see what Dolly has become, it doesn’t have much to say about how she got there. She was not born in a theme park. And while the house where she really was born is not far away, there’s no point in trying to get to it. She owns it and has renovated it, and it’s off-limits. You can see a replica of part of it at the Chasing Rainbows museum, with the newspapered walls and twig cradle and lard-can lunch pail, but it’s a meticulously edited copy of an interpretation of a memory. As is often the case with Dolly, there are lot of metaphysical booby traps between her and us.

And that sort of pun, which she relishes, is one of them. She puts her bust front and center; she calls its components Shock and Awe. There is rarely an appearance where she doesn’t make a joke about them or acquiesce in someone else’s. A weatherman conducting a remote interview the next morning pulls this one out of the trunk: “Here they are, Dolly Parton!” She laughs—that donkey-wheeze—and all but slaps her knee. Is it genuine? Are they genuine? They are certainly a work of art and perhaps, as such, defy the question. They also seem to defy physics. A moderate volume of the World Book encyclopedia, say M, could fit nicely in the gap and stay put. At the museum, as I study the swan-shaped bodice seams on some of her archived outfits, I wonder if I misheard Summers when he mentioned F.I.T. He must have said M.I.T.

It’s as if her body were not a part of her but a gift she’s made to the nation. When she appears at the Dollywood opening of an acrobatics show preposterously called Imaginé, she is wearing a skintight gold-lamé gown; the audience laughs (with her), as she tries to bow without toppling over. “I’m the only person who ever left the Smoky Mountains and took them with her,” she says.

Except, of course, that she didn’t. She certainly left the mountains, as quickly as she could; she moved to Nashville the day after she graduated from high school, in 1964, and met her husband a few hours later outside the Wishy-Washy Laundromat. By 1967 she was a rising country star. But the other “mountains” arrived later, as photos of her as a young woman prove. In a group portrait from her senior-class trip to Washington, D.C., she is dead center in the front row: a small, pretty, well-proportioned girl, with big hair, a nice but not freakish bust, and perhaps a tendency to facial plumpness.

Not anymore. There is nothing on her face today that is not streamlined and taut. “If I have one more face-lift,” she likes to say, “I’ll have a beard.”

Dolly has an apartment in Manhattan, but often prefers to stay in her deluxe tour bus, which she moors in New Jersey when she’s visiting the city. One day in February, a black Escalade ferries her to a 9 to 5 work session at the New 42nd Street Studios. She’s in her version of office attire: a teal leather jacket with a matching T-shirt, knee-length pants, and buff open-toe platforms. After offering more MoonPies and GooGoos, she sits down to discuss changes to the score since the show tried out in Los Angeles last fall. She puts on a pair of glasses that are so heavily trimmed in rhinestones they appear to be made of nothing but.

For someone who had never written a show tune—and who, by her own admission, had slept through some of the few Broadway musicals she’d seen—the prospect of composing the songs for 9 to 5 was daunting. She wondered if it was “beyond my country, white-trash nature.” But not for long; directly after Robert Greenblatt asked her, she “went home and dragged out my old script and just kind of piddled around to see if I could even do it,” she says. “And I wrote a few things, sent ’em to him, and I said, ‘Am I anywhere in the ballpark of what types of things you’re needing?’ ” If not, she assured him, she wouldn’t be offended; they could go ahead with the production using another songwriter and still feature the title song.

But the woman who had improvised that exuberant tune and jotted the lyrics on the back of her script during a quick break in filming the movie—the rhythmic figure was worked out on her acrylic nails because she didn’t have her guitar nearby—turned out to be as fluent in this genre as she had been in the many others her restlessness had led her to over the years. You don’t put out 75 albums and write some 3,000 songs (“But only three of ’em are any good,” she jokes) if your imagination is stingy. She knew how to find musical and lyrical hooks for dramatic situations. As a description of a harried office worker’s morning routine, “Pour myself a cup of ambition” is hard to beat, even if ambition is meant to rhyme, in country music’s less-exacting style, with kitchen. Finding new ways to allow for dramatic development within a song—not just variant restatements of the same theme—turned out to be harder: “I’m even more limited than most ’cause I just know a few chords and I done wore them out!” But the show’s music staff helped her, taking her recorded demos and fleshing them out into Broadway-style routines.

The limiting factor for Dolly, as always, wasn’t inspiration—she’s a melody machine—but organization: keeping track of all the lyric phrases, title possibilities, guitar licks, and snippets of tunes she’s constantly scribbling on legal pads or recording on the kind of key-chain gadget you use for remembering what groceries you need. “I’ve written as many as seven, eight, ten songs a day,” she says—and indeed, at Dollywood I heard her hum a tune unconsciously while waiting out a commercial break during a televised interview and then suddenly take note of it. Steve Summers says he often finds scraps of paper covered with writing when he checks her outfits after they’ve been worn, on their way to her 24,000-square-foot, humidity-controlled clothing warehouse.

When I ask her on another occasion how she makes use of material that could so easily be lost, she says that she used to let it lie around in boxes. “But my little friend right there”—she points to Judy—“she’s got her little crowd together now, and they go through it, put them all on a tape and then title them. Or they just write if it’s a slow song or a fast song or a slow-fast or half-assed!” She guffaws. “In fact, we went over to see Jane Fonda’s show the other night”—she means 33 Variations, in which her 9 to 5 co-star plays a musicologist doing research in the Teutonically organized Beethoven archives. “And we got such a kick out of it because of how they categorize. We got so many good ideas of how to file and store things!”

Those ideas will be put to use. In all, she wrote about 40 songs for the new musical, of which only sixteen remain. It broke her heart to lose the good ones—but she may sing some as bonus tracks on the cast album; others will go into the archive for recycling. And there are always more. When asked at the work session to provide some new lyrics, she tosses off a few immediately and then, taking notes on a legal pad silently provided by Judy, promises to come back the next day with a bunch of “ors.” One time she said, “I’m gonna go pee and then I’ll have it,” and she did.

Dolly doesn’t mope. No one involved with 9 to 5 has seen her “play the Dolly card” or get angry. She doesn’t fret about the show’s run. (“It’s either going to be successful or it ain’t,” she says, and anyway she’s got an autobiographical Broadway musical in the works.) Likewise, if she’s tired (as she says), it doesn’t show. At the Marquis Theatre one morning earlier this month, after busing in from Nashville the day before, she looks perfectly turned out and game for anything. “I’m an energy vampire,” she says. “I just suck off everybody’s energy, but I give it back.” She almost dares me to ask her something tawdry: “What else ya got?” But like the fan in the hilarious documentary For the Love of Dolly who finds Judy’s car in a mall parking lot and can think of nothing better to do once inside than lick the seat belt on the passenger side, I find myself deranged by her openness. The oddest thing I can think to ask is whether, with new deals in merchandising, real estate, touring, and recording all in development, she’ll ever say it’s enough.

“Never!” she answers. “I want to be like one of those little fainting goats that get scared and then just fall over. I want to go and go and then drop dead in the middle of something I’m loving to do. And if that doesn’t happen, if I wind up sitting in a wheelchair, at least I’ll have my high heels on.

“It’s not like this is a job that I hope I do good at. It’s a joy, and it’s just my nature. And I’ve made it into something I can make money doing. And thank God for that. Because nobody can ever make enough money for as many poor relatives as I’ve got. Somebody’s got a sick kid, or somebody needs an operation, somebody ain’t got this, somebody ain’t got that. Or to give the kids all a car when they graduate. Let them shine, let them do what they want to. And not just family—it’s for a lot of other people to have their dreams, too. Going into a new business, you make a certain amount of money, build your name, build your brand, and it’s prestigious, but it gives other people opportunities, too, even if it’s not something I particularly want to do myself. I’m creating jobs”—her various enterprises already employ more than 3,000 people. “I’m like Obama!” she crows. “O-Dolly and Obama!”

The president doesn’t wear much lamé, but the comparison is otherwise striking. Both have succeeded by carefully sculpting—not disowning—their outsider identities. Literally, for Dolly: Though she is frightened of plastic surgery, her desire, she says, is greater than her fear. If something needs tightening again, she’ll do it. “I’m a proud person. I’m not vain. I look at it like it is. If you’ve got the money and you’re going to be out there, you owe it to people not to look like a dog if you can help it.”

Remaining a pinup deep into old age would be an untenable contradiction for most women; even that Barbarella turned workout queen Jane Fonda let go of such ambitions eventually. But for Dolly it’s no contradiction, because the Backwoods Barbie image was always an essential part of her, even before she had the means to express it. “It was never a marketing tool,” she insists. “People say that, but I dress this way for the same reasons I did when I first started doing it. It still comes from a serious place inside of me. I get up in the morning, and I think I just look better a certain way I do my makeup. I want to shine, I want to glitter. I’m not getting up thinking, ‘Oh, this’ll get ’em.’ And I’m not doing it to make a statement. I’m just doing it to look like Dolly—the Dolly that I know and the Dolly that you know.”

I’m reminded of something her full-time wig wrangler, Cheryl Riddle, said at the Chasing Rainbows museum, standing at a computer kiosk that lets visitors “try on” Dolly’s signature hairstyles. While there are 30 to 40 wigs in circulation at any one time, they vary only a shade or two, and beneath them Dolly keeps her real hair just about the same color and length. Steve Summers made the same point when I asked him what Dolly looks like when she isn’t being “Dolly in quotes.” “There is no ‘Dolly in quotes,’ ” he insisted.

People make the mistake that such a complicated authenticity is imitable—hence the Dolly impersonators and seat-belt-licking fans. And seeing where she came from is illuminating in some ways: When you get lost in the heavy mist for which the Smokies are named, you suddenly understand the landscape of wraiths and lonely women that populate her songs. I nearly missed my plane trying to drive through that mist, but the words of her great bluegrass lament “Little Sparrow” made deeper sense to me. The “precious fragile little thing” that nevertheless flies over the mountains has done something amazing, like Dolly herself: With its small head, big chest, and long talons, it has soared on pure instinct to the world beyond its home.

Which is why the real Dolly can’t be found at Dollywood. It was only in the New York recording studio—in the isolation booth—that I felt I really saw her free. Singing “We both know that I am not what you need,” as a thousand tossed-off licks and curls drifted to the floor, she was completely alone with someone, maybe the only one, who completely understood her.