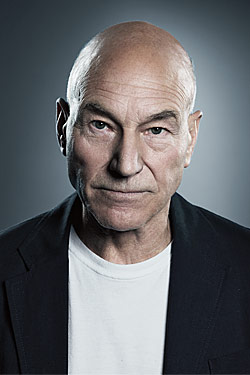

Normally, on a morning like this one, Patrick Stewart would be walking briskly up West 4th Street, muttering to himself. The 70-year-old Shakespearean master, better known as Captain Jean-Luc Picard, is finishing rehearsals for David Mamet’s two-man play A Life in the Theatre, and he likes to use his morning commute from Soho to the Atlantic Theater’s rehearsal space on 15th Street to run his lines. “I totally fit in in New York,” he says. “Here, you mutter on the street, and people just assume you’re crazy or you’re an actor. As long as I cover my head, I can go anywhere I like.” He’s wearing a newsboy cap.

Stewart prefers a “very regimented” daily routine. He wakes up early, makes his tea, reads the newspaper, listens to BBC’s “World at One” radio news as he showers, and walks to rehearsals, to which he is never, ever, late. He is so unwavering that when we walk into the local newsstand, the clerk immediately whips out a copy of the Guardian from behind the register. “We sold out this morning,” says the clerk, who adds that he always sets aside papers to protect regulars against a sudden influx of London tourists. “I think when I first came in, they thought I was just passing through,” says Stewart, “but now they’ve been persuaded that I will show up. I’ll be here, hopefully, for months”—Life is booked through January 2—“and,” he adds for the clerk’s benefit, “I get the Sunday Observer.”

Today, Stewart has allowed himself leeway to meander with a journalist, even though our leisurely pace seems to stress him out. He will stop for coffee and a bagel at the Grey Dog and take me by his favorite architectural finds. Back home, he’s spent the last five years channeling his passion for pediments into remodeling a ten-acre property outside London; here, he spends a lot of time reading historic-building plaques. “Look at this fountain!” he exclaims, as he exclaims each time we pass a fountain, this one at Jackson Square. “It’s glorious! And it’s working! In England it would just be gathering dust and dirt and leaves.” Also on Stewart’s tour: the door of a townhouse built by Revolutionary War general John Sullivan, and the church of Our Lady of Guadalupe at St. Bernard’s.

Stewart first came to New York in 1971 for Peter Brook’s famous “White Box” production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. “But that doesn’t count,” he says, explaining that his real time as an honorary New Yorker began when he started making regular trips here for theater and films in 1990. Every time he comes back, he tries out a new neighborhood. Last time it was Tribeca, for easy access across the Brooklyn Bridge to BAM, where he was playing Macbeth. Directed by Rupert Goold and set in a regime resembling the Cold War Soviet Union, that production went to Broadway. It was also filmed for PBS, where it will premiere October 6. The production was a triumph for Stewart, who says he had to figure out how to play a role usually taken by a 40-year-old. His thinking: “Macbeth was lacking in the hunger for power that would ultimately lead him to murder and mayhem, but was married to a much younger, sexy woman with drive and ambition whom he was crazy for, and wanted to make her happy in every way.” It is entirely coincidental that Stewart met his girlfriend of two years, 32-year-old Brooklyn jazz singer Sunny Ozell, at the end of the BAM run. Though, you know, good for him, and—given how Stewart looks today in a snug Brooklyn Industries T-shirt—good for her. (Stewart’s sexiness is no surprise to Star Trek fans, of course.)

A Life in the Theatre’s themes likewise resonate with Stewart’s experience. It’s about the relationship between a young, talented actor (played by T. R. Knight) and an older, more experienced one, and we see it develop over the course of 90 minutes and 26 scenes. Stewart first played the role in the West End five years ago, as part of a concentrated effort (five Shakespeare plays, Ibsen’s The Master Builder,Waiting for Godot) to revive his London stage career. He says he enjoyed Life so much that, after the London run, he shot off a note to Mamet asking him to keep him in mind if it went to New York. Nine months ago, Mamet got in touch. After overseeing the first rehearsals, he gave Stewart a T-shirt bearing the logo of Yorkshire Gold tea, because he’d seen him drink it constantly.

And speaking of single-minded enthusiasms: Yes, Stewart expects that a percentage of Life’s audience will be fans of Star Trek: The Next Generation, as it always is. His Trek co-stars and producers, with whom he is still close after nearly 25 years, also will come to see it, as they always do. In the past year, Stewart has gone to two Star Trek conventions in the U.K., and others in Sydney, Melbourne, Philadelphia, and Atlanta. He enjoys the travel and the reunions with colleagues, but he also sees the conventions as a great tool for audience recruitment. “I always spend time talking about the theater that I’ve been doing, encouraging them to come and see me if they can,” he says. He believes his solo adaptation of A Christmas Carol—opened on Broadway in 1991, then remounted in six Decembers—owes its success to buzz built through Star Trek fan clubs, which sold out the first weeks. “I am completely pragmatic,” he says. “Without Next Generation, nobody would have put me alone on a Broadway stage in a suit with a few bits of furniture performing a 150-year-old script.”

Once Life ends, Sir Patrick, who was knighted this past June, will go back to film and television, and to preside over the youth-development program of the Huddersfield Town soccer club in his native West Yorkshire. He’s also occasionally teaching at the University of Huddersfield, where he is chancellor and two years ago became a professor in the drama department, “which, given that I left school at 15, is quite ironic,” he says.

On the corner opposite the rehearsal space, Stewart, as he’s been doing all morning, puts out his arm to block me, then checks both ways before gesturing me across. He has what he describes as a “real phobia of getting knocked down in an American street, lying there, looking at the sky, and being really cross that I wasn’t dying in the U.K.” He threw caution to the wind just once, earlier in the morning, upon seeing two giant inflatable rats on Spring Street. Once he learned they were not ads for exterminators but a labor protest, he jaywalked over to learn more. Two workers handed him a flyer and explained their complaints against Bernini Construction. “Well, I have a long history of being a union man. My father and me,” said Stewart. “So I give you my support.” “Appreciate it,” said one of the workers, then leaned in to get a better look under Stewart’s cap. “Hey, did anyone ever tell you you look like that actor?” “All the time,” said Stewart, gesturing at their shiny bald heads. “You look a lot like him, too.”