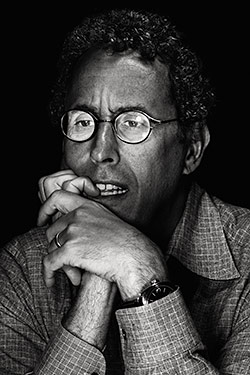

Of the 100 or so books Tony Kushner lugged to Provincetown for a four-week holiday this summer, about the trashiest was The Oxford Book of Death. He gestured toward it on a bookshelf in the penitentially furnished guest bedroom he was using as an office. “Do you know Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks?” he asked, petting another spine. Also handy were The Theory of Revolution in the Young Marx; Dionysius the Pseudo-Areopagite; treatises on suicide, Lenin, longshoremen, Horace, red-diaper babies, and probabilism.

Even Brecht, his hero, read detective novels for pleasure, but if you’re Tony Kushner, to whom everything is a dialectic, your concept of vacation will challenge your concept of vocation, and lose. Or something very different from either will emerge: a weird amalgam of cooking, board games, procrastination, paralysis, and the fear, often realized, of disappointing others. For Kushner, the conflict between being a good person and enjoying life—between the community and the individual or, if you like, between socialism and capitalism—is not an abstraction. His 1994 play Slavs! bears the subtitle Thinking About the Longstanding Problems of Virtue and Happiness, and he really does think about them constantly. In the bathroom of a previous house, in upstate New York, he installed subway tile that spelled out WE ENJOY BEING IN THE OPEN COUNTRYSIDE SO MUCH BECAUSE IT HAS NO OPINION CONCERNING US. A touch of ego-deflating Nietzsche in the shower is very Tony Kushner.

So is renting a gorgeous home on Commercial Street and then fretting, in the back, over revisions of a new play about the problem of economic justice in America. (Hence the books.) Officially and with characteristic exuberance called The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide to Capitalism and Socialism With a Key to the Scriptures, it had its premiere at the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis last year and will begin performances at the Public Theater in March, in a co-production with the Signature Theatre. At the Signature, the new play is a tent pole of its hagiographic Tony Kushner season, which begins next week with the first major New York revival of Angels in America and concludes with The Illusion, his 1988 Corneille adaptation, in April. Though the Signature has devoted seasons to playwrights who were younger than Kushner (he’s 54), it has never devoted so much money: Angels alone, says artistic director James Houghton, is “the largest project we’ve ever worked on.”

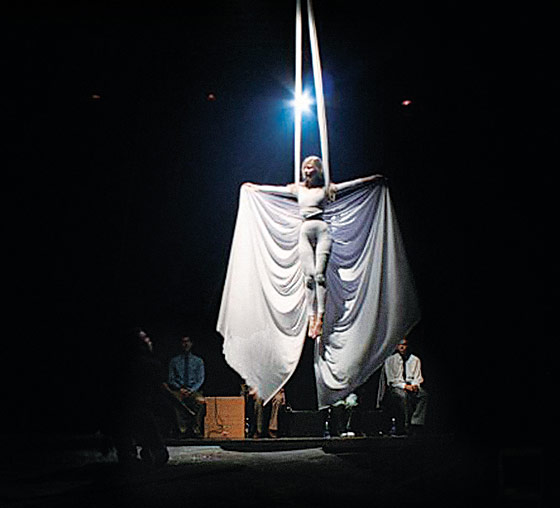

The canonization of Saint Tony—complete with miracles and a few stigmata—comes at an odd moment in his professional life. As a dramatic writer, he has never been more popular. The Signature sold all 10,000 subscription seats for Angels on the first day they were available; 10,000 nonsubscription tickets, released six weeks later, sold within an hour, crashing the website. And it’s not just Angels: Everything but his pocket lint is being remounted. An evening of early one-acts called Tiny Kushner has played Minneapolis, Berkeley, and London. Henry Box Brown, an unpublished oddity he’d all but disowned, was recently resurrected by NYU graduate students. The result is a useful overview of Kushner’s astonishingly fast transformation from early-eighties East Village egghead to Broadway radical darling of 1993. All the ingredients—the political ferocity, the high-low humor, the psychological acuity, the deep river of lyricism and daredeviltry of form—are there from the beginning; in his masterpiece you suddenly see them emulsify.

On the other hand, except for the new play, he has produced nothing big for the stage since Caroline, or Change in 2002. The man who could say, in 2000, “I love movies, but somebody else should write them” has spent much of the interim writing several, including two for Steven Spielberg, no less: the 2005 thriller Munich and an Abraham Lincoln screenplay he thinks may be “the best thing I’ve ever written.” Whether we will ever get the benefit of that achievement is an open question. Liam Neeson, long slated to star, dropped out this summer, leaving the fate of the project uncertain.

Weighing years of potential output in the theater against the inducements even an unmade movie can offer—well, such are the compromise calculations that can distract a progressive artist, if he’s lucky, at middle age. (Is befriending Daniel Craig adequate compensation for ceding copyright on one’s work?) But just as distracting to Kushner have been the compromises of progressiveness itself. He has arrived at the point where what he has created or might create, however valued, is not as politically fungible as what he can say right now from atop the pile of his published works. So the BlackBerry pings. Will you chair the New York Civil Liberties Union’s “Broadway Stands Up for Freedom” fund-raiser? Will you accept the Shofar Award from Central Synagogue and speak to the congregation afterward? What about a rally, interview, petition, preface, panel, blurb, favor for an old pal? Even with a business manager, a lawyer, a personal assistant, and three agents, he cannot handle it all, and his attempts to prioritize just wind themselves into circles. “The primary thing I should do,” he says, “apart from being a good husband, brother, son, and friend, is to be a citizen activist. But I’m afraid it takes away from the writing. Not that anything depends on whether I put an essay in The Nation or not. But you want to participate.”

A Flock of Angels

Two decades of millennium approaching.

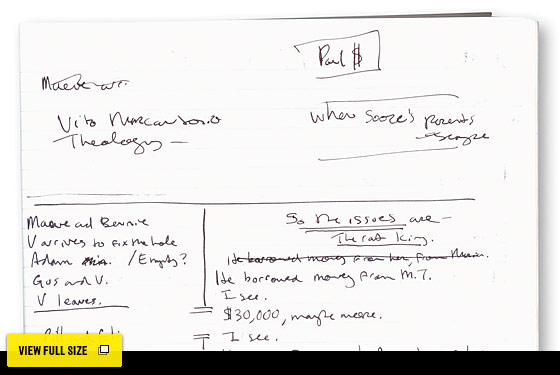

That his writing time must be jealously protected does not mean he uses it more efficiently than when no one wanted anything from him. In Provincetown, the revisions of The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide were not exactly flowing, no doubt because the story hits close to home. Like Kushner’s own family, it features a widower father and three adult children. But in the play the father is a retired longshoreman and Communist Party member who, despairing over the compromises he made, gathers the clan around the dinner table to discuss his plans for suicide.

“I find this particular play very frightening,” Kushner says, “because I don’t feel in control. I don’t know that I’ll get to the bottom of it. It’s about old-fashioned Freudian things like death drives: things that are antithetical to progress and hope. But I have to explore it—not to get rid of it but to give it its full voice and power.”

One Minneapolis critic, in a grudgingly respectful review, said the play skated “precipitously close to the razor’s edge of incoherence.” That edge is pretty much where Kushner aims to be—“at the place where my abilities end.” But in this case he got there inadvertently; thanks to his immersion in Lincolnalia, he wrote much of the play on the fly. On the first day of rehearsal, the cast had no dialogue. By the end of the run, they had perhaps too much: three hours and 28 minutes of operatic family drama, where family is understood to mean not just a brownstone full of squabbling Italian-American leftists but also the country and the world. If the play grew great and cumbersome in its first gestation—the director, Michael Greif, described pages flying out of the printer, with most of the new material “so right that we were able to just incorporate it as is”—at least Kushner shortened the title, for daily usage, to iHo.

Kushner is loyal to gay themes. (In iHo the gay son falls in love with a hustler; his lesbian sister does something decidedly nonlesbian.) As a result, he often seems, in his plays but also in the work that distracts him from his plays, to be the gay world’s leading and perhaps only public artist. Also the theater’s. Also the left’s. There are, of course, gay commentators with a wider audience in America, but they aren’t artists; there are major playwrights who are produced more often, but they aren’t political; there are even a few bedraggled artists (aren’t there?) who sign petitions and talk to Charlie Rose about the redistribution of wealth. But they don’t work in the theater. The kind of figure that flourished in the arts from the fifties through the seventies, often using the stage as a venue—Mary McCarthy, Lillian Hellman, Arthur Miller, James Baldwin, Gore Vidal, Edward Albee, Leonard Bernstein, Susan Sontag, and, later, in his AIDS plays, Larry Kramer—has all but disappeared. Surely replacements exist, waiting in the wings, but the theatrical platform they might in the past have mounted has shriveled almost to nothing. It’s hard to think of anyone but Kushner who has the intellectual heft, the opportunity, and the desire to balance on what’s left of it.

In any case, he tries. But while he can write a commencement address (as one friend put it) “in the time it takes the rest of us to turn on the computer and brew a cup of coffee,” the reputational writing comes insanely slow. The only thing that speeds him up is the passing of a deadline; until then, he desperately pursues distractions. First he must gather the “means of production”: not just reference works but also the perfect fountain pens and notebooks—eighteen for Lincoln so far. Soon enough he’s on Google “and going down a hidey-hole that leads to another and you never get back.” When that pales, there’s always life: e-mail, “closet-cleaning overdrive,” gardening, napping—“and, well, you know, other things.” Kushner performs a Blanche DuBois twinkle, pretending to be embarrassed. “You can become a lotus-eater, or one of those rats that stop asking for food and just die.”

Yet for all his fetishes and distractions, Kushner has produced a dozen or so major plays in the 23 years since he made his professional debut with A Bright Room Called Day. None has saturated the culture like Angels, which ran for twenty months on Broadway, winning two Tony awards for best play and (as he calls it) the Poulet Surprise. Nor has its fame diminished; in this season’s premiere of The Simpsons, we learned that even 8-year-old Lisa is a fan of the “gay fantasia on national themes,” having played the Angel at arts camp.

That Angels came so close to the burning heart of the Zeitgeist left Kushner fearing he would never get there again. But in fact he has been there so often that he seems to have passed right through it. If you reread the plays in sequence, he emerges as a necromancer in black robes, consulting the dead to predict the future. Angels, so much a cry in the dark about AIDS when it was written, seems now to be as much about the Earth’s potentially fatal illness as gay men’s; the writing of Homebody/Kabul anticipated by years the U.S. war in Afghanistan. In East Coast Ode to Howard Jarvis, an unproduced teleplay commissioned by Alec Baldwin, Kushner imagined an anti-tax radical website called www.teaparty .com—in 1996. And though Caroline, or Change, one of the two or three great musicals of the new century, couldn’t sustain an audience when it transferred to Broadway after a sellout run at the Public, it amazingly suggested, in 2002, the imminence of a black (if female) president.

The fate of the actual first black president has been on Kushner’s mind as he takes stabs at rewriting iHo, though the original was inspired, in part, by the Broadway stagehands’ strike of 2007. “I thought all us liberal-shmiberals would be out on the line with them,” he says, “but instead it was: ‘They’re ruining the theater with their featherbedding.’ It was stunning to me, because isn’t the idea of labor unions that you get working-class people to live in nice houses and send their kids to college? It’s great that they’re making $100,000 a year, why the fuck shouldn’t they? Why shouldn’t they have an iPod?”

The strike got him thinking about the “old bad propensity for progressive people, when confronted with triumphant political evil, to take careful aim and shoot themselves in the feet.” The resulting play, he says, “is about a specific issue in terms of the American left, of which I consider myself a part. We are all aware of the monstrous price people pay for powerlessness, but are less honest with ourselves about how, when you have no power, you have some relief from responsibility. To be oppressed is to be given the opportunity to see certain things. It’s better, of course, to have power and try to retain the insight into powerlessness you personally gained or can glean from history. But I don’t know if we recognize the degree to which we’re satisfied with our inability to change. Revolution becomes a fantasy people hold without ever having to be responsible for it. I’m hugely impatient with it now. There is a failure to recognize that the infantile anarchism that was part of the sixties was co-opted by the counterrevolution, by the anarchism of the Reagan years, and turned into a kind of ego anarchism-libertarianism that meshed perfectly with Ayn Rand and all that nonsensical malevolent crap.

“Mark and I just had a discussion about it; we don’t see eye to eye”—Kushner married Mark Harris, a journalist who sometimes writes for New York, before a rabbi in Manhattan in 2003 and then legally in Massachusetts before a “lady motorcycle cop,” in 2008. “But I feel that after Obama’s inauguration the left immediately settled into our very familiar role of being the backseat drivers or principled opposition, and have expressed volubly every disappointment. Not even after the inauguration. The minute they heard that Rick Warren was speaking at the inauguration, LGBT people were saying, ‘It’s over, he’s just like all the others.’ Let alone those who say there’s no difference between Republicans and Democrats, which I think is glib and profoundly dangerous. What frightens me is that I feel that we’re in the process of dismantling the coalition of constituencies that brought Obama to the White House.

“My feeling is that there are too many of us on the left who believe that politics is an expression of personal purity. Because of our divorcement from electoral politics and abandonment of a belief in the possibility of radical change through participatory democracy, we have become profoundly uncomfortable with, and ignorant of, the complexities and discomfort of making change in a democracy. I’m guilty of this in some of the earlier things I wrote, too. I have no illusion of being able to change Rush Limbaugh’s mind, or of being able to make John Boehner anything other than a profoundly indecent person, but what makes something happen in an electoral democracy is compromise, negotiation, and strategizing, and to a certain extent even what in the Clinton era became fashionable to call lying. There are lies, and those should not be tolerated. But there is a degree of rhetorical finesse that’s required to maneuver through very treacherous waters. I’m willing to believe that this man who got himself elected president is actually a very skilled politician and is negotiating imponderably difficult conditions.”

Harris assures me that the rushing streams of talk are not always so high-minded: “He’s surprisingly able to ask, ‘Is there another Project Runway on tonight?’ without its leading to a discussion of the Aeneid.” Maybe so, but the pressure of people seeking wisdom and a million other things from Kushner seems to have overprimed the pump.

“And the LGBT community, what are they, we, looking for?” Kushner continues. “Yes, we’ve been asked to wait a very long time, asked to eat oceans of shit by the Democratic Party; we’ve been 75 percent loyal for decades without a wobble and without a whole lot of help from these people. And it’s important that somebody keeps screaming; the trick is how do you scream, and who do you scream to? If we’re dissatisfied with these Democrats, let’s get better ones instead of fantasies about mass uprisings that are going to resemble the October Revolution. Yes, it might sometimes feel good to throw the newspaper across the room. There’s much criticism of Obama that’s legitimate. He backs down on things, he waffles, like on the mosque, and you wince. And I consider his decision to appeal the Federal court ruling abolishing DADT to be unethical, tremendously destructive, and potentially politically catastrophic. But is Obama really supposed to say, as the first African-American president, that same-sex marriage is his first priority? Clearly he believes in it; he’s a constitutional scholar. It’s not conceivable to me that he believes that state-sponsored marriage should be unavailable to same-sex couples, even if he has religious scruples. But do I think he should have lost the election for the chance to say he supported same-sex marriage? No. Given that we would have had John McCain and Sarah Palin, I would have said, ‘Say anything you need to.’ So if he’s moving very cautiously, with two wars he’s inherited and a collapsing global economy and the planet coming unglued—Okay!”

In Angels in America, Kushner basically clobbers the moral relativism of his stand-in, Louis Ironson. Played on Broadway by Joe Mantello (and in the revival by Zachary Quinto), Louis is a logorrheic gay Jew who leaves his lover the moment the lover shows signs of AIDS. This unpardonable, though hardly unthinkable, betrayal puts him in the doghouse for some six hours of stage time. Mantello, who asked to be dressed in hooded sweatshirts and vintage overcoats like those Kushner wore, says he could feel the audience turn on him—as much for Louis’s cowardice as for his relentless justifications. To hear Kushner, who gave the best lines to the character eviscerating Louis’s defense, offer a brief for patience and compromise is a bit of a shock. Has the man who wrote those blistering scenes—not to mention A Bright Room Called Day, which offers a straight-faced comparison of Reagan to Hitler—mellowed?

“I find this particular play very frightening, because I don’t feel in control.”

Yes and no. He now considers A Bright Room Called Day—about the “tragic failure” of socialism in Weimar Germany—an “immature play.” And while the “self-discipline and regulation” of mature artists like Haydn and Trollope remain somewhat beyond his grasp, he has made a connection between personal and political disorder. “The older I get, the less I see chaos as the goal of anything.” What he feels he has attained, at this “crossover moment” in his life, is a “more complex worldview, with more interesting doubts and confusions.” He is, he says, less angry and more forgiving, and better able to express both in his work.

He is certainly more comfortable with himself. He used to gnaw at his talent as if it were a manacle. Now “he’s made peace with it,” says Oskar Eustis, artistic director of the Public and Kushner’s longtime “comrade.” “He’s still tortured, of course, but not the way he used to be. His marriage has been very good for him in that regard”—even if his public appearances have sometimes left Harris feeling a bit like Pat Nixon, “waving benignly while sipping from a hip flask.”

Kushner’s public appearance has itself changed. The Jewfro of his first fame is now cropped tight; with the help of Weight Watchers, he has dropped and kept off the extra pounds that once made him look less imposing than, at almost six-foot-two, he really is. Still, he mitigates the effect of his beaky, high-domed, El Greco bearing with touches of camp applied like beauty spots. He bats his eyes, refers to his (male) “girlfriends,” plays peekaboo with intimate details. Then he flips right back to Thanatos and the Wobblies in beautifully parsed paragraphs. The alternation is so deft and funny it seems planned, a costume of casualness like his name. (He was born Anthony Robert Kushner.) You can almost read the stage directions—which is not to say he is false. Rather, he’s theatrical: a man of the theater. Serious past anyone’s requirement, he is also in every sense playful.

This is much more evident now, in what he calls “the Meistersinger years,” than it was in his youth. His origin story is, like his dramaturgy, a cabinet of curiosities: the “fairly chaotic” household of New Yorkers displaced to Louisiana, the clarinetist father and bassoonist mother, the hearing-impaired older sister, the musical younger brother, the bizarre combination of cosmopolitan culture and southern gothic. He was free to roam the “riverine, woodsy” landscape of his neighborhood but was left in the dark about matters closer to home. His mother’s disappearance during a harrowing bout of breast cancer when he was 11—she was poisoned by over-radiation after a mastectomy and only survived thanks to two surgeries over a period of six months—was explained in the local manner: “She was fine and in New York shopping and was way too busy to write.” His sister, Lesley, now a painter living in Brooklyn, was determined to discover the truth, but Kushner preferred to distract himself with anger: a version of the avoidance of emotional pain that is at the heart of his difficulty writing.

In any case it was, he feels, a sign of a kind of attention deficit that produced his magpie erudition. That he eventually pinned that erudition to the stage may be another of his mother’s inadvertent gifts; she was, he says, “the local tragedienne,” playing Betty the Loon, Mrs. Frank, and an “indelible” Linda Loman at a community theater in Lake Charles. In kindergarten, after seeing her carried into Freud’s office and laid on a couch in the melodrama A Far Country, Kushner got sick, became paralyzed, “and had to be carried to my bed.” In that strange, almost hysterical identification with a character played by his mother, many of the strands of his adult personality and profession find their origin. “It was then I became a playwright,” he says.

Also, one might infer, a dedicated analysand. His faith in therapy is so conflated with his progressive politics that he sometimes comes off as the commandant and sole internee in an endless reeducation camp. (To his non-fans, his plays feel like much the same thing.) It is one of his best features that, however grand he gets, he sees himself coming from miles away: the pretentiousness, the too-muchness, the debilitating anxieties that no real activist lets get in the way. But it is sometimes unclear whether his willingness to absorb all censure, and trump it with his own, is a sign of radical vulnerability or a diabolically clever defense against it. Into one of his iHo notebooks he has pasted a copy of a letter he received from Eustis’s stepfather, a very thoughtful old communist who took issue with the play’s portrayal of the radical left. But the man’s neatly typed criticisms do not compare with some of the things Kushner himself scrawls in the notebooks, such as “I don’t know what the fuck I’m doing and I’m going to die in the gutter.”

Hollywood has paid him handsomely, though. It has also repaired the “bitter disappointment” he felt early on, when his television and film work had yet to achieve what he most wanted from it: “to provide its author a pretext to meet Meryl Streep.” (Streep starred in the 2003 HBO mini-series of Angels; the next year Kushner held her umbrella at a New Dramatists luncheon.) Though he struggled to adjust himself to a visual medium, he doesn’t disdain the product as many playwrights do: “The Wire and now Breaking Bad are the best drama being written anywhere,” he says. “It’s a race to the bottom to see who can depict the most awful things most truly.”

The Lincoln portrait isn’t that kind of story; Kushner took pains, he says, to avoid the feeling of a mini-series or “a pageant at the Mall of America.” And he has accepted not having the last word—as if a writer ever does. His Munich screenplay, intended as “a critique of state vigilantism,” had Israel absolutists apoplectic, and he is often the object of ad hominem—sometimes creepily homophobic—attacks for his politics. But within the theater his stances only enhance his status, and he gets what he wants. “Look, if you’re lucky in my profession,” says Eustis, “you encounter someone who you just believe in absolutely. I believe in Tony absolutely. He is the greatest living playwright; that’s a slightly provocative statement as long as Edward Albee is alive. He knows, although he acts sometimes like he doesn’t, that he has a standing offer from me to produce anything he wants me to produce.”

Keep in mind that this comes from a man who, after working on early versions of Angels for years, and co-directing the Los Angeles production, was basically fired by Kushner as the play headed to Broadway. (George C. Wolfe took over, to great acclaim.) Loyalty came in second place to what Kushner saw as the needs of the work—or, looked at less charitably, to ambition. It was, after all, the moment of his big break, and for a playwright those moments are surpassingly brief and rare. Of course, they are also brief and rare for directors. In any case, though the two men fell out for a year or two, they managed to repair the relationship to the point that Eustis, not exactly a meek personality, could say recently that it is sometimes the joy of his professional life “to carry Tony Kushner’s bags.”

“He wishes I was being ironic,” Eustis adds now, “but I wasn’t.”

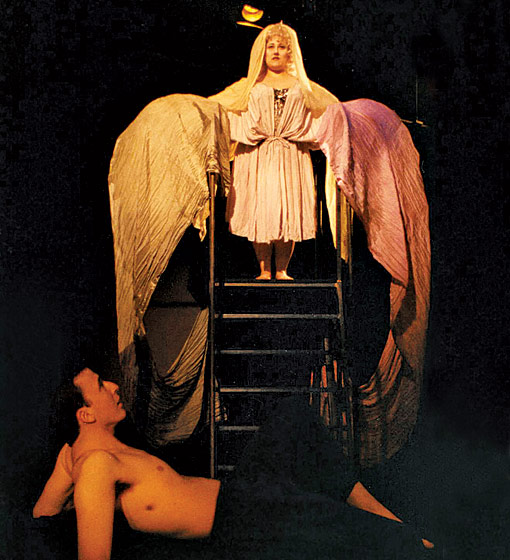

The switch, and others like it, established Kushner’s reputation as a tiger in the guise of a pussycat. The reputation isn’t quite right; his sweetness is no less genuine than his fierceness, though it took a while before the fierceness (like his gayness) came out of the closet. When the playwright and actress Ellen McLaughlin met him in 1984 at the New York Theater Workshop, where he was associate artistic director and her play The Narrow Bed was in production, Kushner was so modest she couldn’t get a bead on him. “I asked him what he did,” she recalls, “and he said, ‘I sort of do plays and have this company,’ and I thought, How sweet. Then he showed me A Bright Room Called Day and I thought, Oh, fuck, he’s a genius!”

At the time McLaughlin had a little more clout than Kushner, and helped him get an agent. Later, when cast as the titular semi-deity early in the development of Angels, she was able to watch the Eustis drama, and many others, play out as if from above. “The promises you make when you’re in the happy thick of a great rehearsal process are not always promises you can keep,” she says. “And sometimes if you can keep them, it hurts the production. The thing about Tony that anyone who’s ever worked with him knows is that he’s simply not afraid of hurting people or pissing them off, because his dedication to the work is absolute. I admire that, but I’ve watched people suffer for it, and have been winged a few times myself. He gives notes that are difficult to hear or take in, he sheepdogs directors until he gets them to do what he wants”—true to form, he has attended almost every preview of the Angels revival, offering sheaves of opinions. “And radical rewrites come in far, far past the tolerance of a cast—some on the last preview, thank you very much! But then you look at the rewrite and it’s, well, brilliant, so what are you going to do?”

“Too many of us on the left believe that politics is an expression of personal purity.”

McLaughlin, like others who “became inessential to his work,” bears no malice toward Kushner. Rather the opposite: She misses his “remarkable company,” the “fireworks display of his mind,” and even the harness and twenty-pound wings that once let her fly onstage. Playing the Homebody in Seattle was “the most amazing thing I’ve ever gotten to do as an actor,” she says. “I suspect the reason no former colleague speaks with much bitterness about Tony,” she adds, “is that the good times were just too good to be completely poisoned by whatever happened after.”

And yet the irony is too rich—too Kushneresque—to leave at that. “Tony writes a lot about accountability,” says Mantello, who remains an unreserved admirer. “It’s almost poetic that it’s the thing that keeps him up at night. How am I going to be accountable to my collaborators? The dilemma is a human dilemma and the contradiction is in all of us. But it’s more acute in artists with superhuman standards like Tony. And what happens when your life’s work is about community but you have these other things inside of you that contradict what you’re writing about? Didn’t it blow your mind to find that Arthur Miller had a son he put away?” A recent biography revealed that the author of All My Sons—a play about man’s responsibility not only to kin but to all humankind—institutionalized his Down syndrome son at birth and never spoke of or to him again.

Well, Williams was a pill-popper, O’Neill a drunk, Brecht a womanizer. By the standard of the modern playwrights in his own pantheon, Kushner really is a saint: the soul of probity, kindness, and social engagement. And though he has certainly lost friends, he seems to have spent his professional life seeking to disprove Auden’s dictum that real artists aren’t nice: “All their best feelings go into their work and life has the residue.”

To the extent he has succeeded it is because there is such an extraordinary amount of feeling to begin with. It spills over the banks of the plays. He has compared the process to making a proper lasagne: “All the yummy nutritious ingredients you’ve thrown into it have almost-but-not-quite succeeded in overwhelming the design. A play should have barely been rescued from the mess it might just as easily have been.” What some critics find overstuffed and argumentative, others find rich and, in its refusal to dictate answers, humane. “The idea isn’t to hector people,” Kushner says. “I don’t know how to get out of the morass, either. I just know that there’s a great deal of value in not running away from it. That’s why we made this weird activity”—theater. “So we could find social occasions to encounter these things. If you have value as an artist it’s probably going to be in your capacity to let things inside you get past things that are placed there to keep you from telling the truth. The more you see things as clearly and coldly as you can, the more value you’re going to have.”

Kushner freely admits the process isn’t good for much but the play. “When really writing I’m not a good friend. Because writing disorganizes the social self, you become atomized. It scrambles you, sometimes to the point that I’m incapable of speech. I feel that if I start speaking, I’ll lose the writing, like getting off the treadmill.”

But few try harder to live up to their ideals. And where should a playwright be his best self but in his plays? Kushner’s have the double vision of how things are and how they ought to be, the latter shadowing the former, sometimes as angels, sometimes as ghosts. (Sylvia Kushner died, after a recurrence of her cancer, in 1990.) His plots are therefore very crowded, but they gain power from that: “He puts almost indigestible things at the center to force them to expand, to force human insight,” says Eustis. Among those indigestible things are Ethel Rosenberg saying Kaddish over Roy Cohn in Angels, and Laura Bush reading Dostoyevsky to dead Iraqi children in Only We Who Guard the Mystery Shall Be Unhappy. And among the resulting insights are that people are not one thing or another but both; that they may betray and still be loved; that even as Louis Ironson can grow, so can a president, so can a country, given time and emergency. After all, it was that gradualist Lincoln who brought off the most radical change in American history.

“It’s about the messianic moment,” Kushner says, “making a leap of faith that you can change things you thought couldn’t change. We should recognize in developing a complex and somber view of the world that at some points recklessness counts. ‘I don’t know if this going to work, but let’s try it.’ ”

He’s talking about supporting Obama in the same terms he uses to describe his lasagne dramaturgy. Yet finally, it’s harder than it sounds. In writing Angels, Kushner struggled with the fate of Louis Ironson, who can’t reasonably leave the story when he leaves his lover in Act I. “It took five years to get Louis to come back into the hospital room,” says Eustis. “Finally Tony brought in the scene near the end in which Louis says, ‘Failing in love isn’t the same as not loving.’ It took him that long because he had to figure it out as a human being. It was his synthesis of the contradiction between freedom and responsibility that’s at the heart of Angels: Freedom doesn’t let you off the hook, and failing doesn’t mean you’re not responsible for trying.”

Nor, Kushner might add, does success.

San Francisco

Eureka Theatre Company, 1991

Photo: Katy Raddatz/Museum of Performance & Design

New York

Walter Kerr Theatre, 1993

Photo: Joan Marcus

Kansas City

Unicorn Theatre, 1996

Photo: Cynthia Levin/Courtesy of Unicorn Theatre

HBO

2003

Photo: HBO/Everett Collection

Alameda, California

Encinal High School. 2008

Photo: Courtesy of Gene Kahane

Evanston, Illinois

Northwestern University. 2009

Photo: Courtesy of Geoff Button

Salt Lake City

Salt Lake Acting Company, 2010

Photo: Thom Gourley

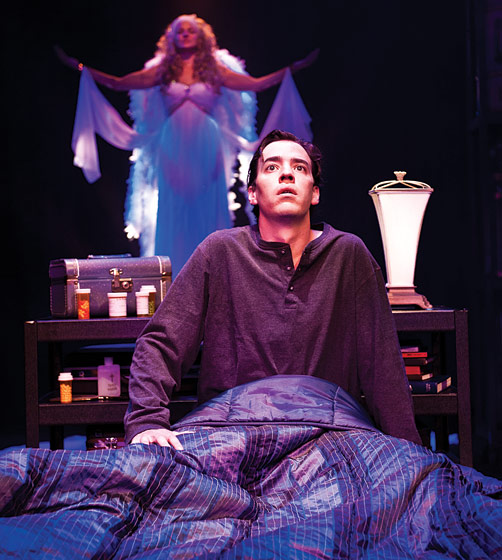

New York

Signature Theatre, 2010

Photo: Joan Marcus