Just try it, hipster. Try to sit through the first two minutes of Tarzan, Disney’s latest big-budget Broadway musical, and act blasé. When you take your seat and a storm-tossed ship seems to float holographically before you, pretend you’re not intrigued by how the Imagineers did it. When a blast of lightning kills the lights, and the kids in the audience scream, deny that you yelped, too. Because when video projections, rumbling sound, and bodies twisting twenty feet off the ground combine to form a startling image of shipwrecked survivors trying to claw their way to the beach, no matter how cool you like to act, you are going to be amazed. Briefly.

Then you are going to be bored. Until Tarzan, I’d never seen a show begin with such flair only to dribble its ingenuity away. Directed by longtime designer Bob Crowley (who recently did The History Boys), the show transforms the stage of the Richard Rodgers into a three-dimensional jungle bonanza. But where Julie Taymor had the storytelling knack—and enough puppet-y tricks—to keep The Lion King engaging, Tarzan follows those two awe-inducing minutes with two yawn-inducing hours.

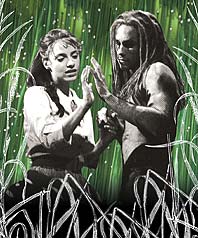

Though it’s ostensibly a tale about a boy who was raised by apes and discovered by Brits, Tarzan’s true subject is the winch. Hoisting and lowering, lowering and hoisting: All night long, Pichón Baldinu, the man behind the aerial carnival of De La Guarda, fills the sky with acrobats. Disney, deep-pocketed as ever, makes sure that some very fine actors are hanging inverted in fringed ape suits up there. Shuler Hensley, a wonderful Jud in Oklahoma! a few years back, plays Tarzan’s grumpy ape dad; Jenn Gambatese is the cute naturalist who stumbles upon, and falls for, the dirty dreadlocked star.

But what’s there for all these talented people to do? Even by Disney-musical standards, there’s not much depth or flavor to the relationships. David Henry Hwang’s libretto imposes not one but two montages on the action (a bold move, and not necessarily a wise one, after Team America discreetly slaughtered this device). This is a show in which people straight-facedly tell other people to follow their hearts.

This is also a show scored by a pop songwriter whose big hits lie a generation or so in the past; in other words, it’s the latest in Broadway’s long gray line. This season alone, new musicals have featured songs by (or associated with) John Lennon; the Four Seasons; Johnny Cash; Earth, Wind & Fire; Elton John; and now Phil Collins. There’s something funny, but not ha-ha funny, about how Broadway lags so far behind what’s interesting in pop music, then wonders why its audience is dying off. Collins’s original music here is livelier than, say, Lestat’s, but seems more striking for the chances it lets slip.

One chance in particular: As Seaweed in Hairspray and Jackie Wilson at the Apollo, Chester Gregory II was tear-the-roof-off exciting. He’s in the role of Tarzan’s pal here, and his voice, moves, and charisma are wasted. Who needs millions for screaming flying monkeys? Give this guy a microphone and get out of his way—there’s your special effect.

I don’t mean to sound like a Luddite. It’s true that I found John Doyle’s rigorously low-tech, high-imagination approach to Sweeney Todd vastly superior to this synthetic display. But the tools used in Tarzan have their seductions. The flying and swinging have been boosted from nouveau cirque, the nimble projections and film montages come from the better sort of movies and DV, and it’s all woven together with more computing power than all Broadway possessed when The Phantom of the Opera premiered. So far, neither Tarzan’s creators nor anybody else has figured out how to make these 21st-century wizardries cohere onstage. But one day somebody will, and if the material and the storytelling are up to snuff, even the most jaded spectators will have to swoon. Where are you when we need you, Orson Welles?

Meanwhile, at the Biltmore, Brían F. O’Byrne is playing the tortoise to Tarzan’s hyperbolic hare. In Conor McPherson’s new drama, Shining City, he is Ian, a Dublin therapist whose problems rival those of his patients. There’s no flash in his two-hander scenes with his castmates, nothing showy or forced—just the best example yet of his quiet brilliance, an awesome display of the actor’s craft.

When we first see Ian, O’Byrne appears studious in rimless eyeglasses and a sweater vest. Without saying a word, he suggests an overgrown altar boy, an uncanny foreshadowing of what’s to come. As he listens to the testimonies of his patient (Oliver Platt), O’Byrne’s control is nearly microscopic, suggesting Ian’s inner state by the set of his jaw, the lift of his chin. This proves useful, since even in Robert Falls’s careful staging, these scenes feel endless.

McPherson’s writing—a tiny panorama of lonely Dubliners, with the occasional burst of the supernatural—more than once offers you the chance to nod off, but O’Byrne’s volatility keeps you watching. When Ian’s girlfriend (Martha Plimpton) arrives, he switches from feeling guilt about leaving her to rage at the thought of her with another man, suddenly clamping his fists around her arms. Can any actor play the extremes of vulnerability and menace the way he can?

Last comes a late-night visitor (Peter Scanavino), who plunges Ian into psychic torment. I don’t want to give the scene away, but O’Byrne shows he can make Ian’s poise melt in a flash, or let it thaw gradually over what seems like a full minute of silence. In both cases, the performance is fearless. O’Byrne slips into character the way a brush takes paint, and we’re lucky to watch him work.

BACKSTORY

For a show that had no out-of-town tryouts, Tarzan has seen a long, hard road to Broadway. The creative team trekked to Buenos Aires last April to witness De La Guarda creator Pichón Baldinu’s flying techniques. They proceeded to have the actors practice over mats in a gymnasium upstate for five weeks before upgrading to a full-scale set at Brooklyn’s Steiner Studios. Then followed an unprecedented six-week period of reduced-price weekend previews at the reengineered Richard Rodgers Theatre, allowing audiences the rare privilege of an actual bargain—paying less than they would to see Julia Roberts and Paul Rudd rehearse.

SEE ALSO:

Q&A with Shining City star Brían O’Byrne.

Tarzan

Lyrics and music

by Phil Collins. Book by David Henry Hwang. Richard Rodgers Theatre.

Shining City

By Conor McPherson. Biltmore Theatre. Through July 16.