When Richard Greenberg told The New York Times Magazine a few months back that he has seen The Light in the Piazza many times because “it’s a place you just want to return to,” I didn’t know what he meant. It’s never occurred to me to feel that way about a show. Then I saw his new play, The House in Town.

As you enter the Newhouse at Lincoln Center—downstairs from Piazza, as it happens—the stage is decorated with plush couches, tall windows, a glittering chandelier, a Tiffany lamp, and a wall of books; the décor creates the distinct sense that someone nearby is mixing martinis. Ultimately Greenberg’s play let me down; still, as I looked upon this slice of vanished New York, I found myself thinking, This is a place I want to return to.

While he’s admired for his sharp wit and teased for his elaborate vocabulary, Greenberg deserves acclaim for writing sensitively about time and how it passes, pulling scenes out of it for our contemplation. As in The American Plan (set in the summer of 1960) and The Violet Hour (the wake of World War I), he once again shows us a world on the brink of upheaval and populates it with characters who greet it, or fret about it, with relentless eloquence.

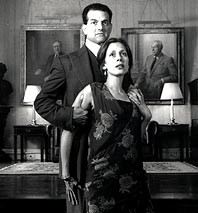

On Millionaires’ Row—23rd Street between Ninth and Tenth—in early 1929, the verbose, uneasy Amy Hammer (Jessica Hecht) is leaving her child-bearing years, joining the club her friend Jean (Becky Ann Baker) calls “Les Dames d’un Certain Age.” Husband Sam (a wonderfully nuanced Mark Harelik) runs a prosperous store and nurses his secrets. All the while, the hulking complex of London Terrace is being built across the street, casting literal and metaphorical shadows over their lives. “As each evening ends, a little grief,” Sam likes to say.

The setting and the sense of melancholy recall Dinner at Eight, particularly when a certain melodrama creeps in. (What does the doctor tell Amy about her condition? Why does Sam seem so attached to the recently orphaned young clerk in his employ?) Alas, the script lacks Kaufman and Ferber’s precision crafting. The first hour or so is devoted to talky exposition, leaving the action to transpire at the end, when most everyone’s attention has waned. The story feels more novelistic than dramatic, which is unusual for Greenberg; one of the things I love about his best writing, in Three Days of Rain and especially in Take Me Out, is its vivid theatricality.

Once the action finally arrives, it culminates in what might be Greenberg’s most negative finale yet, and his most evocative. Amy delivers an aria about the armistice, a story full of sad wisdom. Like this play, it concerns the hard, painful reality that’s left when all the pleasant lies are gone—the disillusionment that so many Greenberg characters, in so many different times and places, have encountered. In a deftly understated touch, he nowhere depicts, and barely mentions, the real ending of this tale: the imminent market crash, which would sweep people like these characters away. Many playwrights could have avoided this play’s mistakes, but I can’t think of any other who could have attained its heartbreaking virtues.

At Lincoln Center, Greenberg’s play was preceded by a house manager’s announcing—loudly and slowly—that patrons should please turn down their hearing aids before the show began. A little feedback isn’t likely to bother anyone at the Atlantic, where composer Duncan Sheik and lyricist-librettist Steven Sater’s new version of Spring Awakening explodes in a burst of power pop. It makes intuitive sense to tell Frank Wedekind’s story about nineteenth-century German teenagers’ discovering sex with a score derived from rock music, the sound forged by the baby-boomers for precisely that purpose. Yet director Michael Mayer finds countless ways to improve on the conceit, with mostly fantastic results.

At times the show looks less like a play with music than like a concert with narrative. Songs that begin as solo complaints—about distant parents, school troubles, various flavors of unrequited love—again and again build to choral finales, a stylish way to express the old truth that adolescent woes are universal. Even better, although the costumes and clunky, old-timey dialogue pin the students in the 1890s, the songs—the moments at which they express their deepest, truest selves—are brightly modern. Outward distances notwithstanding, it has always sucked to be hormonal and 15.

The cast’s eleven young actors lend the kids distinct identities (line-for-line, my favorite was Jonathan B. Wright, who plays the deadpan gay seducer), but the real source of the show’s personality is Bill T. Jones. With quick, gawky movements and stagewide full-cast eruptions, his dances do a marvelous job of capturing youthful energy while broadening the show’s themes and tone. That’s lucky, because Sater’s lyrics are uneven at best, lapsing too far into slang (“We’ve all got our junk, my junk is you”) and generally failing to sustain much interest. Whenever the cast sang without dancing, I tuned out.

The show, like its subjects, works best when it’s carried away. After one of the kids gets busted at school, the anthemic “Totally Fucked” briefly turns the stage into a dance party; the sheer exuberance expressed in movement and song makes it one of my favorite numbers of the year. If Disney can make the soundtrack to its TV movie High School Musical into a smash, this ought to run for years.

BACKSTORY

Richard Greenberg’s clearly the playwright of the moment. But can he bring in the cash? Of his two commercial Broadway runs, the first—Take Me Out—had a critically acclaimed eleven-month run (at one point it was the only straight play on Broadway) but failed to recoup its investment. The second, of course, is Three Days of Rain. A moneymaker for him in the past (he once called it his “cash calf”), it just recouped in its limited run thanks to Julia Roberts’s drawing power. Many of those tickets, however, were snapped up early by brokers—who expected skyrocketing demand but, following terrible reviews, have not only had trouble marking tickets up but have been selling them below face value—as low as $75 for orchestra seats. So we’ll put an asterisk on that one.

The House in Town

By Richard Greenberg. Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater. Through July 30.

Spring Awakening

Music by Duncan Sheik. Book and Lyrics by Steven Sater. Atlantic Theater Company. Through August 5.