No matter how many times I read or see it, King Lear scares the hell out of me. This is not a play like other plays. At the height of his powers, Shakespeare extracted from some dark corner of his brain the most aggressively nihilistic drama ever written. A man’s mind and body crumble, his state collapses, his daughters betray him (before turning on one another), and, when the storm rages, even the cosmos itself seems to be caving in. Call it romantically excessive, but I sometimes think that to express the full terror of this play—in which a bystander quite reasonably wonders if he’s witnessing the apocalypse—you need to follow the play’s destructive logic to its conclusion, and wreck the theater.

The Public not being the sort of place where a director can wantonly punch holes in the ceiling, James Lapine has sought other ways to convey the story’s traumas. In the revival that opened there last night, he introduces the figures of Lear’s daughters as little girls, who torment him with spectral reminders of the family life he’s thrown away. Forgoing coy suggestion during the icky parts, Lapine also makes spumes of “vile jelly” jet out from Gloucester’s face when the poor man loses his eyes. There’s an excellent score by Stephen Sondheim and Michael Starobin, and enough fine performances in knotty roles to make my friend and I agree, when the show ended, that it had been well done.

Yet after a little reflection, I’m troubled by how untroubled we were. Lear is a play that, if it’s truly working, should be so devastating you have trouble expressing how devastating it was—the theatergoer’s corollary to Edgar’s “the worst is not / So long as we can say ‘This is the worst.’” Lapine’s often admirable production resembles too many Shakespeare revivals lately: Despite having plenty of talent and material resources on hand, they leave you suspecting you’re not hearing all that he was trying to tell us. If the staging of a play this overpowering can’t provoke the supreme reactions you read about in books—the silent curtain calls, the waves of grateful tears—how can any at all?

In every case I can think of, the trouble begins with the stars. Again and again lately, the desire to play the roles that have inspired four centuries’ worth of over-the-top purple critical prose has led fine actors into performances that were lackluster or worse. Denzel Washington’s Brutus, Jennifer Ehle’s Lady Macbeth, Michael Cumpsty’s Richard II: However different their shortcomings, the collective result has been to tame Shakespeare’s great roles, making them tidy, decorous.

If anyone could save us from that pedestrian fate, you’d think it’d be the actor long since tagged “America’s Olivier.” But Kevin Kline’s recent encounters with the Bard show that he’s all but the apotheosis of the trend toward prim, polished Shakespearean heroes. At Lincoln Center four years ago, he played Falstaff with admirable thoughtfulness and aplomb, but little of the fat knight’s messy Dionysian charm: He guzzled sack with pinkie extended. Now the same tendencies return—not exactly helpful in playing the vengeful pagan king who “hath ever but slenderly known himself.”

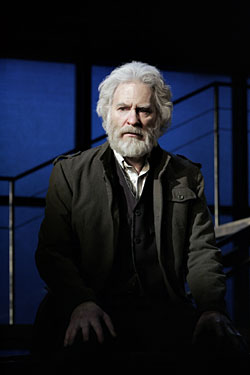

You can see how easy and difficult a time Kline is going to have as Lear in his opening moments. Tall and fit, in purple coat and white beard, he ambles toward his throne, giving the immediate impression—I don’t know how the great ones do it—that he means business. When he gives an order, he has the easy, authoritative air of one used to giving them. So he’s in good shape as he approaches Lear’s first hurdle, the perverse demand that, as he divides his kingdom among his three daughters, they must publicly proclaim how much they love him. When Christopher Plummer played Lear, he treated it as a way to torment Cordelia—a hint of wickedness that made it easy for him to clear the second hurdle, disowning her and banishing loyal Kent for her refusal to comply. Kline does the opposite. He makes the professions of love seem an amiable jest, a little diversion. Unfortunately you can’t get from that tone of mild, harmless fun directly to “Peace, Kent! Come not between the dragon and his wrath” and expect the imprecation to have much force. Playing this scene in fashionable waistcoats and gowns, with no crown or weapons in sight, the actors don’t look like they’re depicting the breakup of a royal family and a kingdom’s collapse—it might be a rude remark spoiling a pleasant tea at a country estate.

Nobody who’s seen Sophie’s Choice should doubt that Kline can unleash an old-school freak-out when an unbalanced character demands it. As Lear treks out into the storm, he musters some agreeably topsy-turvy exchanges with the Fool (the excellent Philip Goodwin, loping around in Harpo-ish yellow curls) that make you feel your own sanity beginning to slip away. He also dreams up some vivid, delightfully dirty uses for the crown of weeds he wears during one of the scenes on the heath. But just as often he shies away from the outbursts that most actors give their reputations to attempt. “O, let me not be mad, not mad, sweet heaven” doesn’t have the urgency of one who feels himself on the brink. When Alvin Epstein played the scene in which Lear, now completely shattered, says Gloucester shouldn’t shake his hand because “it smells of mortality,” the sight was unbearable—pitiful and terrifying at once. When Kline says it, he gets a laugh. A little humor and some pockets of lucidity help speed the story’s route into the abyss, of course. But somehow Kline—ruminating on madness, forever inclining to the comic—over and over gives the impression that he’s showing us what it might be like if he played King Lear.

The wobbles at the show’s center mean that, as in so many other Shakespeare revivals lately, it’s the supporting players, the ones without the legend-making soliloquies, who carry the emotional load. The story of faithful, naïve Gloucester, his treacherous bastard son Edmund, and good son Edgar shows what happens when the city’s awesome acting talent is put to proper use. As Edmund, Logan Marshall-Green flashes real charisma, flinging himself off the platform at the back of the stage onto the sand-covered floor below. (There is a great deal of scampering up and down steps in this production.) Alas, he seems oddly uneasy during Edmund’s soliloquies about how he’ll turn his father against his brother to seize an inheritance—a real problem when playing that snaky charlatan. More impressive is Brian Avers, who’s terrific as both Edgar and his mad, mud-spattered alter ego, Poor Tom. When his blinded father appears, their recognition scene is genuinely heartbreaking. “Might I but live to see thee in my touch, / I’d say I had eyes again!” says Gloucester to the son he doesn’t realize is standing before him. The great Larry Bryggman all but sings the line; his command of the actor’s craft is so good at moments like this you don’t notice the craft.

It’s typical of this play that Edgar has to show filial devotion by helping his father seem to kill himself, the better to restore his will to live. It’s typical too that the skinny, bookish youth’s path to manhood will be strewed with violence—first killing a man to save his helpless dad, then squaring off at the end against his own brother. It makes for one hell of a fight, as these things go. Marshall-Green is at his best here, as his swagger makes you think Edgar really is going to have his head handed to him, and fight director Rick Sordelet, drawing from his inexhaustible bag of tricks, works fresh variations on the art of who-will-reach-that-stray-knife-first.

If the story of Gloucester and his sons seems to lack the payoff its best moments promised, don’t blame the actors. Like many directors before him, Lapine has punched up the action in ways that spoil what the Bard was trying to do to you. Few moments in this horrible story are more devastating than Edgar’s speech after vanquishing Edmund: We think he’s about to say that their father will live out his years in comfort; instead he tells us the old man has died. By interpolating a death scene for Gloucester earlier, Lapine loses the gasps and sobs I’ve heard that speech provoke—not least in me. He does the same thing by adding a little stage business so we can see how Goneril (Angela Pierce) poisons Regan (memorably bloodthirsty Laura Odeh). There’s usually a dash of gruesome, no-she-didn’t awesomeness when Goneril reveals why her sister has been moaning and stumbling around for a scene or two. Now we watch them just waiting for the poor girl to keel over. If Lapine was trying to set up a tableau of corpses, the reward wasn’t worth the price.

How, then, does this revival still deliver a satisfying final act? Casting has something to do with it. Kristen Bush, alas, misses Cordelia’s poetry, but as the doggedly loyal Kent, Michael Cerveris, trailing clouds of Sweeney glory, exquisitely registers the terror of all the bloodshed and mayhem around him. So does Michael Rudko, who, with his mustache, glasses, and faint air of disapproval of all the bad behavior he’s witnessing, makes Albany seem—quite properly—like the small-town banker in a Capra film. And then there’s Kline.

One of the marvelous things about Shakespeare’s great roles is that they’re so huge and various that an actor of sufficient stature will sooner or later find some scenes that fit. For Kline, those scenes arrive when Lear, recovering from his ordeal, speaks with a hard-won, philosophical wisdom—that is, when he treads closest to Hamlet. When he tries to cheer Cordelia by describing how they’ll pass the time in the prison where Edmund would consign them, Kline’s delivery is quiet, intimate, and, for once, all the sadder for being a little funny. At the end, with the dead Cordelia sprawled on his lap, he takes “Never, never, never, never, never,” not as a final trailing away, the way Plummer did, but slowly, thoughtfully—wonderfully, in fact. He beats his chest on the last one, adding a little extra emphasis, as he falls backward.

It’s gratifying to see Kline finish strong, if not surprising: The kind of rhetorical prowess these last few speeches demand are what he does best. (Where Shakespeare is concerned, “America’s Gielgud” is nearer the mark.) A great Lear, though, needs to express the extremities of the king’s torment with an eloquence that’s physical as well as vocal, outsize as well as intimate—something this still-young 59-year-old doesn’t do. Still, his best moments inspire two hopeful guesses: First, the burdens of age can only help him reach those elusive tortured heights and depths, good news if his circuit of the great roles brings him back to this play at 69 or 79; and second, when that circuit carries him to The Tempest—as you know it eventually will—his Prospero is going to be amazing.

King Lear

See schedule and slideshow