In this second year of the Bridge Project—director Sam Mendes’s two-play, two-state solution to the union-enforced London–New York talent divide—we’ve learned something important. Despite the proprietary hand of Mendes (palpably felt in every carefully staged moment), the souls of these shows ultimately belong to their lead actors. Last year, the Project’s animal spirit was Simon Russell Beale, with his flop-sweat genius for extravagant mental squalor and wounded, wonderfully neurotic fatality: His jealous King Leontes (in A Winter’s Tale) and his reluctant usurper Lopakhin (in The Cherry Orchard) were intertextual twins: both outsiders in their own houses, both pitiful (and consequently pitiless) victims of their own sprawling insecurities. Beale, apart from supplying two extraordinary performances, was generous with his stage energies, and the rest of the (quite excellent) ensemble benefited enormously from an anchor-tenant of such largesse.

Well, S.R.B., thou thrice-named villain, thou art sorely missed. This year, the stage belongs to the chilly, brilliant yet diffident Stephen Dillane, perhaps best known to American audiences for his chilly, brilliant yet diffident Thomas Jefferson in HBO’s John Adams (and for his Tony-winning turn in The Real Thing, which broke him open a bit, with stunning results). Dillane is the center of Mendes’s tidy pairing of Shakespeare’s As You Like It and The Tempest that’s thematically cogent to the point of feeling almost collegiate. These shows run like clockwork and, unfortunately, also feel like clockwork: Cogs acting upon cogs, all very prettily mechanical but far too controlled to seem even a little rude—or much fun. Too often, the proceedings feel purely ceremonial, like unthawed dramaturgy with no patience for the messy give-and-take of living theater.

Dillane, doubling as the melancholy Jaques in AYLI and the godlike Prospero in The Tempest, sits (well, slouches, really) on the throne, withholding all. If there’s a single word to describe both his performances, it’s “downcast.” He can work a fine sulk with a jeweler’s hand, but spiritually and energetically, the guy’s a real skinflint. He plays everything so close to the vest, it’s practically inside the vest. He broods. He ferments. He seems to yawn inwardly with every line he’s tasked to speak. We in the audience follow suit.

Dillane isn’t going rogue here: The mood of general depletion seems to be entirely by design. Mendes strenuously fosters a recession-era vibe (especially in AYLI), from the etiolated lighting to the costume design, which is somewhere between Sullivan’s Travels and The Blues Brothers on the colorless-rumple continuum. If his aim is merely to channel this achy gray zeitgeist we’re having, he’s done a bang-up job. Mendes cites, as his inspiration, Ted Hughes’s interpretation of The Tempest as a kind of postapocalyptic epilogue to As You Like It. Fair enough, but his pre-apocalyptic Arden looks pretty blasted already: dirty and cold and full of hobos.

In As You Like It , these frowsy forest-dwellers were, until recently, well-tended courtiers: The good Duke Senior (Michael Thomas) has been banished to the Forest of Arden by the bad Duke Frederick (also Michael Thomas), in the usual Bardic upending of the political order. Having lost everything, the Senior Administration gains insight into the Good Life, wryly idealized as a bucolic Robin Hood fantasy—and ironized just as quickly by Jacques, the good duke’s resident gadfly. (Senior is too grounded and Obaman to keep a mere fool on his payroll.) Meanwhile, back in the evil city, Duke Frederick’s daughter, Celia (Michelle Beck), watches, with alarm, as her father’s roving Nixonian eye falls on her more-than-sisterly companion Rosalind (Juliet Rylance), daughter of the exiled Duke and perceived enemy of the state. Complicating the situation, Rosalind’s fallen in love with hunky, naïve Orlando (Christian Camargo), also on the outs with the new regime. Both find themselves separately banished. Meanwhile, a horny clown (Thomas Sadoski) woos a happy tramp (Jenni Barber), a loyal old retainer (Alvin Epstein) expires in his master’s service, and a doting shepherd (Aaron Krohn) pines for a haughty country wench (Ashlie Atkinson).

Yeah, it’s quite a bramble. As You Like It might be Shakespeare’s wooliest and most ungovernable comedy, a Rousseauesque wilderness of semi-serious town-versus-country tropes and borderless gender play. One could easily see in this a ripe burlesque of the new, resurgent populism. Or one could see it, as Mendes apparently does, as an opportunity to have actors deliver speeches—as much to themselves as to each other—against the stylish backdrop of his exquisitely sparse stage pictures. There’s nary a laugh, even a rueful one, to be had in this “comedy,” and you can’t really blame the wintry mood. The cast simply feels paralyzed, looking more posed than directed, with no proprioceptive feel for themselves or their scene partners. Words are spoken, various coups de theater come and go, people marry and die, and none of it feels terribly important. (Anthony O’Donnell, in the tiny role of Corin the Shepherd, practically steals the show, just by being loose and human for five minutes of vaudevillean banter with Sadoski’s Touchstone.) Dillane looks more or less at ease, but only because he’s alone with himself up there, needing nothing and no one. He gives the distinct impression of meeting no one’s eyes. A rather overextended Bob Dylan impression in an early scene signals both the actor and the director’s intentions here, but this Jaques comes off less Don’t Look Back than Don’t Care Much. By choice or by chance, Dillane looks trapped in his own head. And either way, I’d submit, it doesn’t work.

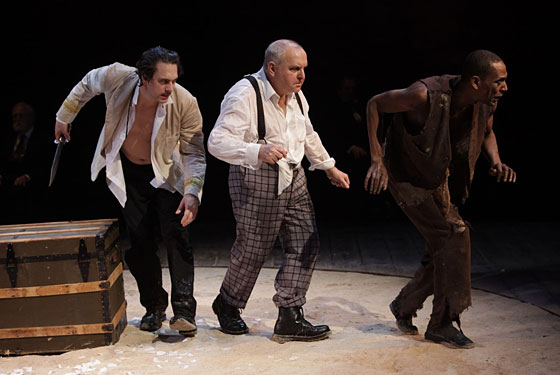

This syndrome carries over into The Tempest, which, while considerably cleaner, brisker and less leaden than AYLI, suffers from many of the same problems: affectation without inflection, gesture without intention, a jangly quality to even its most liquid moments. Dillane has a dash of Charles Manson in his Prospero, and hints of cruelty and distracted rage constantly threaten to enliven his performance. Yet he always retreats, as does Mendes: The production is a magic circle the director himself keeps fecklessly breaking. No choice seems to occasion a meaningful consequence: Caliban (Ron Cephas Jones) is played for laughs, with the Stepin Fetchit stuff pushed uncomfortably to the brink, yet there’s no follow-through, no accompanying sense of social destiny. A homoerotic feint with Ariel (Camargo) goes nowhere; a jarring segment where Prospero plays Super-8 home movies for Miranda (Rylance) and her new fiancé Ferdinand (Edward Bennett) splatters against the bare back wall of the Harvey, but with no strong emotional underpinning, it slides off as casually as everything else. Prospero’s daughter bores him, and why shouldn’t she? He has no equal on the island. He’s God. He must converse with the audience, the only thing bigger than he is, if he’s to converse with anyone. But Dillane can’t be bothered. In the end, he asks us, with more toleration than conjuration, to “release me from my bands / With the help of your good hands,” and finishes with the famous, “Let your indulgence set me free.” Personally, I couldn’t help but feel, a little ungenerously, that Dillane—and his director—might’ve been indulged enough already.