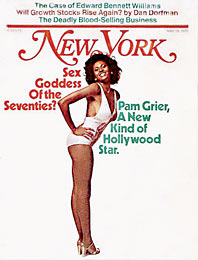

I’m worried about meeting Pam Grier, if only because the last time she hung out with a New York writer, in 1975, she ended up punching him in the nuts. The writer, Mark Jacobson, was asking for it, literally: He was about to take a swing at her on a dare, when—whammo. Otherwise, they had spent their time together much more genially, bopping around Times Square, dodging “small-fry super flies in rainbow shoes and felony hats,” and pondering together whether the bootylicious 25-year-old Grier might represent a brand-new, revolutionary kind of sex-and-race symbol.

But that, of course, was a different New York, and a different Pam Grier. This time around, we meet in a French restaurant in midtown east, where the clientele is sadly rainbow-shoe-and-felony-hat-free. We’re joined by the publicist for The L Word, the show on which Grier currently stars, which launches its fourth season on January 7. Back in 1975, Grier was a newly minted curiosity, the jaw-dropping, jaw-breaking star of blaxploitation flicks such as Coffy and Foxy Brown—subversive, explosive movies that weren’t so much about introducing the mainstream to black urban culture as they were about declaring that black urban culture couldn’t care less what the mainstream thought.

Thirty-odd years later, Foxy Brown is now the name of a sexed-up rapper, and Grier is a well-aged 57-year-old icon—though an icon of what, exactly, is unclear. She’s one of those free-floating icons who appear where they’re needed. As a co-star of The L Word, on which she plays Kit Porter, a straight older sister to Jennifer Beals, Grier’s become a lesbian-circuit celebrity. And she’s picked up a few pointers about her new audience. “I’ve learned that there are straight lesbians, then women who are a little bit of lesbian, then women who are a little bit more. There are various levels,” she says. “There are women who look so masculine on the outside, and who have full beards. There are women who have chest hair but have the genitalia of a woman, and her birth certificate says she’s a woman, and she’s struggling. Should she kill herself because no one understands? Or is too lazy to understand?”—and here she switches to her girlfriend, you know it inflection, which she keeps at the ready. “And I am tired of the laziness,” she says. Grier has a few strong opinions, by the way—on race relations, on global warming, on Osama bin Laden, on the general overabundance of intolerance in the world. “When we had 9/11, the world shut down,” she says. “They didn’t hit the New York Trade Center, they hit the World Trade Center. They attacked the world, saying, ‘Please—leave us alone.’” She sees a parallel here to her work on The L Word, adding, “With the gay-lesbian- transgender-bisexual community, we’re not leaving them alone. We’re including them. Which I feel is so important.” She’s happy to share these thoughts with you. After all, she’s had people watching her for 30 years, so she is used to being paid attention to.

“As a woman of color, you’re not going to be the leading lady. Is that going to make me feel horrible about myself?”

Most people have histories. Icons have mythologies. Here’s the myth of Pam Grier. She arrived in Hollywood as a Colorado bumpkin and former Air Force brat, driving a dented truck and wearing white gloves and a pillbox hat. She caught the attention of Roger Corman, who cast her in The Big Doll House, a prison film with the tagline “Their bodies were caged, but not their desires.” She treated her first roles like Chekhov, she says. She read Stanislavsky. She went to the Philippines to film Doll House with a suitcase held together by one latch. Later, when she met Tamara Dobson, the star of Cleopatra Jones, Dobson showed off her Louis Vuitton luggage. “Is that like Samsonite?” Grier asked. Fast-forward to Coffy in 1973, which earned millions on a paltry investment. Soon she was partying with Sammy Davis Jr. and dating Richard Pryor.

But just because you’re an icon doesn’t mean you’ll always be relevant, or even employable: Only six years after Foxy Brown, Grier was doing a guest spot on The Love Boat. For years, she survived on cameos that winked at her past. So when Quentin Tarantino cast her as the lead in Jackie Brown in 1997, she’d essentially been rediscovered—the bonus being that it turned out she could actually act. Tarantino had similarly rehabilitated John Travolta, another discarded icon, in Pulp Fiction. But unlike Travolta, when Grier made her comeback, she discovered there was nothing really to come back to.

“For Jackie Brown, I had the best PR person, who taught me everything,” says Grier. “She said, ‘Pam, the reality is, you’re a black woman. You’re not going to be on the magazine covers. You’re not going to sell to the masses. You’re not going to appeal to the little farm girl in Idaho. So I’m not going to make you pay me just for the rejections.’” When The L Word premiered in 2004, Grier was a perfect addition to the cast: a well-known but not particularly busy star who could give a new cable show credibility even as the show gave her a steady job.

Meeting Pam Grier back in 1975, you’d be happy to survive the encounter. She said then, “Right now I’m setting up my own production company. I know I can do it. I read the trades, I know I’m big.” She had plans to produce, to self-finance, to become the first black female to direct a major film. If that didn’t pan out, who could blame her? She was simply young, black, and beautiful, a lovely form on which to drape the flag of cultural change.

Talking to her now, she’s the one who sounds like a survivor. “As a woman of color, you’re not going to be the leading lady,” she says. “Is that going to depress me and make me drink and feel horrible about myself? I can’t let that happen to me.” She may have played a part in opening the way for Halle Berry and Beyoncé—but don’t forget, she’s still around, too. “How do you survive and have a career for 35 years? There are people who aren’t as old as my career,” she says. And the onetime Foxy Brown has learned some lessons. “The one thing you don’t do is that you don’t go out there and preach and upset people and make them feel uncomfortable,” she says. “It’s like in martial arts—you don’t keep hitting your head on the wall trying to move it. You don’t keep getting angry, saying, ‘You don’t accept blacks, you don’t do this, you don’t do that, you don’t have black television shows’—you know, I leave that to Al Sharpton.”

So instead, she lives in Colorado. She mucks stables and fly-fishes in hip-waders. She thinks about bin Laden. “Oh, we know where he is,” she says. “He’s in a cave! So we’ve got to pretend we’re leaving. Then bin Laden will come out, and if you want to nail him, now you can.” She’s writing a book about her life. And if Hollywood needs her, it knows where to find her. “I’m only a plane ride away,” she says. “People said, ‘Out of sight, out of mind, you’ll never work again.’ But I thought, I can live out here and be happy. I don’t have to live out there and be rejected all day long.”