I confess: I don’t watch Mad Men.

I say this with reluctance, because every time I admit it—to friends, relatives, co-workers, strangers—I’m answered with the same sputtering combination of disbelief, dismay, and disdain. What?! You don’t watch Mad Men? Don’t you understand how good it is? Yes, I do. And as we enter year-end-list-making season, I look forward to being reminded about it again and again (and again). I can’t remember a show that was so universally celebrated since, well, the last show that was universally celebrated, namely The Wire, which wrapped up back in March. And that’s the problem. I’m suffering from Quality Show Fatigue.

It’s not Mad Men’s fault. I recognize that it earned a Sopranosesque sixteen Emmy nominations this year. I accept that everyone around me, like brain-hungry zombies, now seems to have only three objectives in life: (1) eat; (2) watch Mad Men; (3) persuade me to watch Mad Men. I’m also aware that, while it feels like about 2 million people have tried to convert me to this show, there are, ironically, only about 2 million people watching the show each week—or roughly 11 million fewer people than watch House, a show that no one has ever tried to force me to embrace.

Yet this relentless Mad Men campaign has done little to sway me. If anything, it’s the reason I’ve held out for so long. Because I can’t help wondering: As viewers, we’re more atomized than ever, with more options, more channels, and less inclination to hunker down en masse. For a lot of us, our TV-watching habits don’t even involve actual TVs. So why do we still feel this manic need to all coalesce around a single show?

It’s hard to recall the pre-Sopranos TV landscape, way back in 1998. This was before DVD boxed sets and DVR addiction, before YouTube and Hulu, back when HBO was best known for second-run movies, pay-per-view boxing, and a year-old sitcom about four gal pals in Manhattan, starring that woman from Square Pegs. In 1998, we were still living in what might be called the Hill Street Blues Continuum—an era when a slickly produced network drama, complete with entwined plotlines and showy acting and appropriately adult themes packaged in very special episodes, represented the apex of the medium. Shows like ER and NYPD Blue and Homicide: Life on the Street were all considered Very Good Television. But no one quite had the stomach to call them Art.

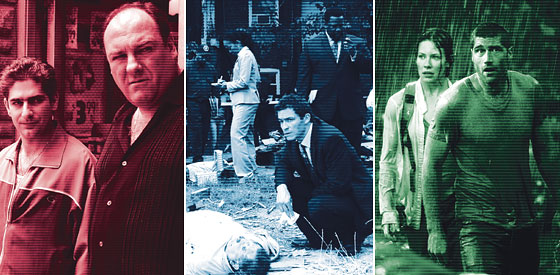

Of course, The Sopranos changed all that. It normalized, then popularized, the idea that a TV show could measure up against the best of any art form. It heralded an age of creative latitude for TV creators, attracting vital talent to the medium. And it coincided with the rise of the Internet, which gave ardent TV fans a new place to gather and whip themselves into a froth—as if the office cooler had been transported into a giant echo chamber. All of which created the perfect conditions for a show to be declared the Best Ever—not just an amusing entertainment but a can’t-miss cultural event.

When The Sopranos went off the air, it was like Einstein hanging up his chalk or Shakespeare retiring his quill. There was no longer a consensus Best Ever to rally around. You’d think it would be years, even decades, before another contender would appear. Instead, a new Best Ever—HBO’s The Wire—was immediately crowned to fill the vacant throne.

Oddly, no one (including yours truly) had managed to figure out how good The Wire was in its first three, underwatched seasons. Then suddenly everyone figured it out. In 2006, every living TV commentator declared The Wire the one show you must start watching right now. And, obediently, we did, beetling through past seasons on DVD and sidestepping spoilers like land mines.

In the process, we’d established a new relationship with our favorite shows. It wasn’t enough to enjoy a series as a pleasing diversion; you had to become a passionate advocate. And every time you turned around, there was a new show-you-must-watch-right-now, whether it was Battlestar Galactica or Friday Night Lights or Damages or Lost. In part, this is because TV really is better than ever, and more deserving of our passion. In part, it’s because watching a particular show is now an active choice—no longer can a show like Night Court build a following simply by being the show that airs after Cheers. And in part, it’s because there is so much more animated advocacy out there that you have to shout to cheer for your favorite. I don’t remember similarly impassioned arguments breaking out in the eighties between fans of Riptide and Hart to Hart.

Which brings us to Mad Men. My aversion has been, I think, a reaction to this phenomenon—this ADD-ish quality in viewers that leads us to collectively anoint a masterpiece every year. The whole process is counterintuitive. The programming universe has been fractured into shards. There are dozens of glittering offerings competing for our eyes. If anything, we should be less likely to rally around a single hit, rather than more so. But recently (actually, while writing this) I started thinking about it differently.

Maybe the furor around shows like Mad Men is not the product of some rampant mass hysteria. Maybe it’s the expression of a yearning for the last remnant of the traditional viewing experience we once shared. Long gone are the days when we would all sit down on Thursday at 10 to watch L.A. Law. So instead, to retain some sense of communal experience, we cling culturally to a single show. We don’t want to admit we’re splitting off in a million directions; we want to believe that all our eyes still occasionally turn in the same direction. (For the past year, the election campaign served this purpose—the one great show we all tuned into.) So it doesn’t even matter that not many people, relatively, are actually watching Mad Men. What matters is that everyone’s talking about it.

No doubt there will soon be another Mad Men—another must-watch show on another channel, with just as many vocal advocates. That idea used to make me weary, but I’m starting to think maybe I should be hopeful. If I ponder Mad Men mania like that—not a herd mentality but an affirming desire for social cohesion—I’m slightly less averse to tuning in. It helps if I think of it as joining in rather than signing up.