I have a little story that I would like to tell you … Do you feel like a story?

Anyone who works at the Ed Sullivan Theater knows that a personal audience with David Letterman is a rare thing, especially just before showtime. But on Thursday, October 1, minutes before the start of the day’s 4:30 p.m. taping, Letterman had summoned about fifteen of the Late Show’s senior producers, writers, and crew members to his dressing room. One producer wondered who had died.

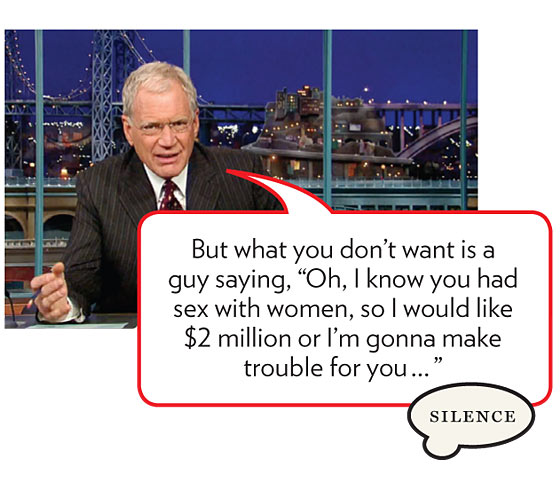

With the small room packed to capacity, Letterman announced in somber tones that he was being blackmailed: A man had threatened to go public with information about affairs he’d had with female staffers of the show unless he paid him $2 million. The assembled group, one source realized later, were only those who would need to know that Dave was going off-script after his monologue. As he spoke, he seemed almost to be rehearsing what he was about to say on the air. “He explained it much as he did on the show,” says another source, “what happened, and what had been threatened.”

The staffers were stunned. They had lived through unusual events in Dave’s personal life: his stalker, the attempted kidnapping of his son, his quintuple bypass. But what seemed different about this moment was the sense of shame emanating from Dave himself. He ended, one source says, with a typically self-conscious, self-lacerating gesture, telling everyone that if they wanted to resign because of what he had just revealed, there would be no hard feelings. No one took him up on it. “I’m sure there were people who were surprised,” says one staffer. “But I think the prevailing feeling was, ‘How can we help?’ ”

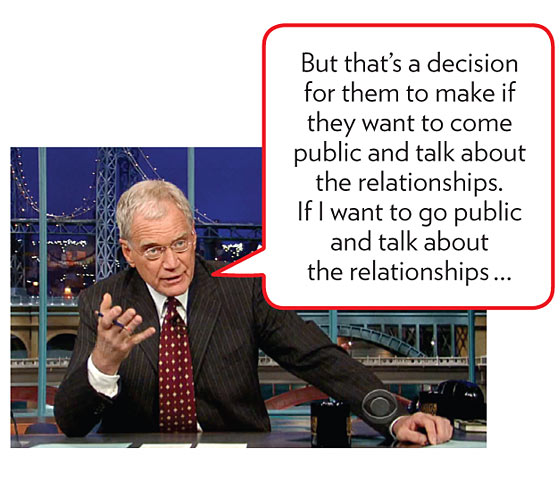

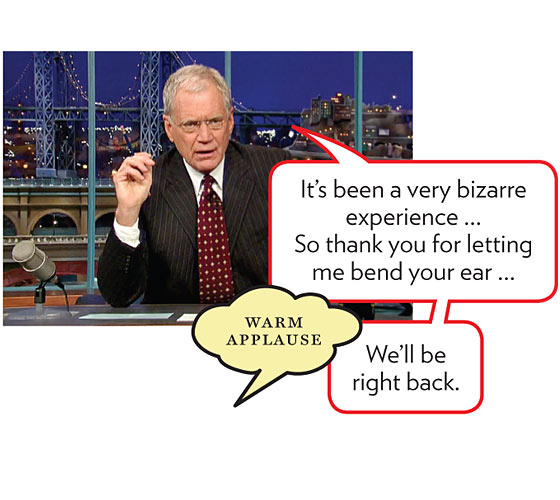

What Letterman said on-air that night was not scripted, at least not by anyone at the Late Show. “Maybe some lawyers had a glance at stuff,” says a Late Show staffer, “but even there, there was no real input.” “Do you feel like a story?” Dave said. Delighted applause. “This started three weeks ago yesterday. And I get up early, and I come to work early, and I go out and I get into my car, and in the back seat of my car is a package I don’t recognize … I don’t usually receive packages at six in the morning in the back of my car.” Laughter. “I guess you can. I guess some people do.” Then he suggested that he was the victim of something sinister. “There’s a letter in the package,” he said, “and it says that ‘I know that you do some terrible, terrible things.’ ” More laughs, some of them uncomfortable now. “There seems to be quite a lot of terrible stuff he knows about,” Dave said about the letter writer. “And he’s going to put it into a movie unless I give him some money. Yeah, I’m like you. I think, Really? That’s a little, and this is the word I actually used, that’s a little hinky.” The biggest laugh yet.

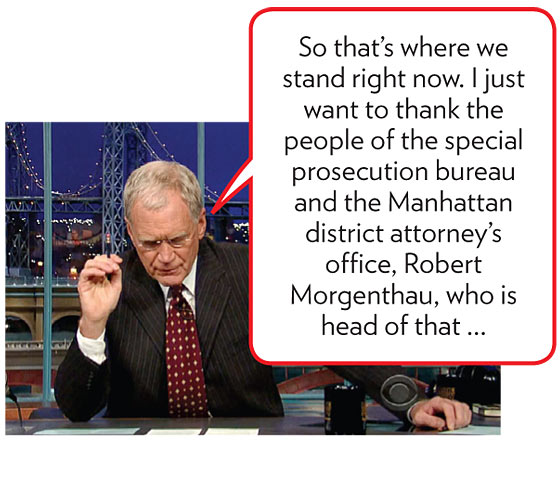

For the next several minutes, Dave turned the spotlight on the alleged extortionist, telling the story of how he, Dave, wouldn’t give in to the man’s demands, how he called his attorney and brought in the D.A. and testified before a grand jury. “And a little bit after noon today, the guy was arrested,” Dave said. The audience cheered.

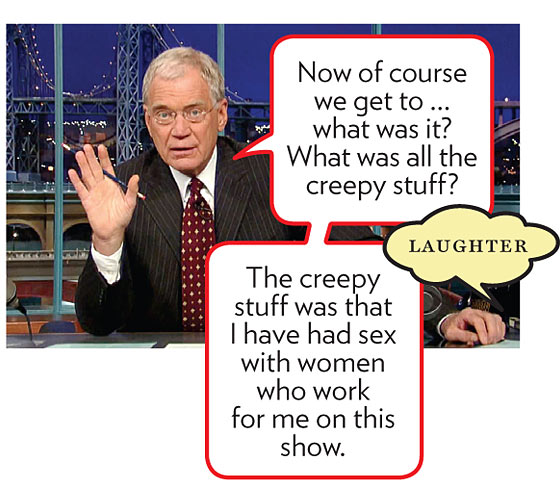

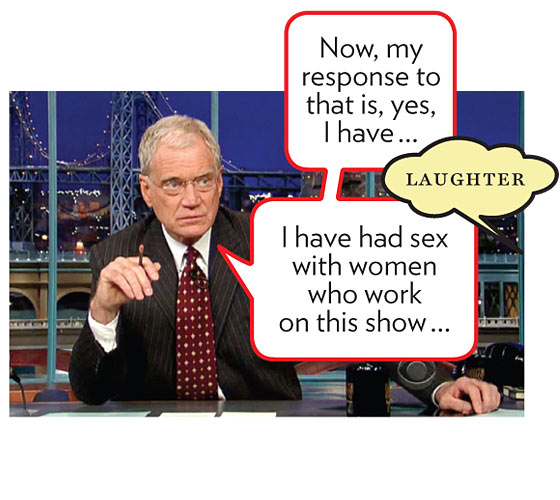

Only then, almost eight minutes into the speech, did Dave reveal what it was that he had done. “Now, of course, we get to, What was it? What was all the creepy stuff that he was gonna put into the screenplay and the movie? And the creepy stuff was that I have had sex with women who work for me on this show … ” Then later: “Now, I know what you’re saying. ‘I’ll be darned, Dave’s had sex!’ ” Another round of laughter. “We’ll be right back … ”

After the taping, Letterman’s publicist, Rubenstein Communications, sent out word that Thursday night’s show would contain a disclosure of blackmail. This was a double-taping night, and so after the show, Dave turned around and taped Friday’s show. Only then, in a postmortem that night with a half-dozen producers, did Dave finally talk about the situation again with the staff. The people around him were respectful. Letterman wasn’t exactly emotional, but he seemed more vulnerable than usual. He came around again, a source says, to the idea that he’d done the right thing by not giving in.

When it premiered in 1982, Late Night With David Letterman featured a host whose entire appeal, it seemed, was wrapped up in his sincerity as a performer. “I think of myself as being in broadcasting and not show business,” he told the profile writer Bill Zehme in an interview that year. “I can’t see myself singing in Vegas.” In time, Dave displayed almost everything the younger Johnny Carson had—the irreverence, the inventiveness, the midwestern outsider’s skepticism, even the charm. Among those Dave personally charmed was his show’s head writer, Merrill Markoe—the inventor of Stupid Pet Tricks, and any number of other conventions that are still a part of Dave’s onscreen identity—whom he once called “one of the smartest people I’ve ever known in my life.” They had begun dating in 1978, before they worked together; Markoe left the show in 1986, and they broke up two years later. But there was always something missing from Dave’s persona, something uncomfortable that brought him down to earth: He never had Carson’s studied smoothness, and rather than try, he ran hard in the other direction. In interview after interview, Letterman was a self-confessed basket case, irritable and unconfident and self-defeating. Not getting the job that even Johnny himself thought he should get seemed to confirm Dave’s outsider status. Letterman never overtly campaigned for the Tonight Show job, but once he lost it in 1991, he made it clear he always expected it. He said at the time he didn’t want to disrespect Johnny by asking NBC to succeed him—but it’s also true that having to ask for it would have meant saying he deserved it, and that was something he could never bring himself to do. “I’m too big. I’m too dumb. I’m too clumsy,” he said, comparing himself to Johnny in 1993 as he was starting his new show on CBS.

Even as Letterman got off to a great start at a new network, his legendary self-loathing remained; he’d apologize to staff members on his way out the door, or tell reporters that the last time he felt good about himself was a Tonight Show appearance he made in 1978. By then, he’d taken up with Regina Lasko, now his wife, who had been a production staffer on Late Night before heading to Saturday Night Live for a short time. Lasko, like Markoe before her, had a great mind. Dave, it seemed, had a type: women who impressed him intellectually, who somehow had his number. They were not necessarily the obvious choices. “You can look at these women and see how they look,” says one former staffer. “You see he’s going for personality as well, but I think he’s also going for easy targets. He’s not setting himself up for rejection. He’s not going to ask the head of the cheerleading team to prom. He’s going to ask the head of the band or something.”

Letterman kept to a small circle of friends, most of them buddies from his L.A. comedy days. Former staffer Laurie Diamond once said she regularly fielded calls from ex-girlfriends hoping to reconnect, but he ducked them. And as the years have gone on, he has cut off his contact with more and more of the people around him at work. There is no more playing softball with the staff, no more kibitzing all day with writers. “After 29 years and thousands of episodes, the process has evolved to where Dave comes into it a hair later than he used to, but he remains as focused as ever on every last detail of the show,” says Rob Burnett, the former Late Show head writer who is now the head of Dave’s production company, Worldwide Pants. To the rank and file of the show, however, Dave is almost a nonentity now. “He and his assistants are literally walled off from the rest of the staff, behind a glass door,” a former staffer says. “There is just no contact.” His absence has brought a new level of palace intrigue to the Ed Sullivan Theater. “There’s a level of mind games and chess that goes on, starting from the top down. They rule by fear. You don’t want to make Dave mad or so-and-so mad, so you better do a good job. Everyone there is scared of their shadow all the time.”

The staff, meanwhile, has swelled in number. Because of the show’s prestige, and because the company is good to its employees, people get promoted and new people come in, but few leave. Yet the show only needs a certain number of people on any given day. “They keep dividing the show into smaller and smaller sects,” says the former staffer. “It’s like tribal warfare. It can’t function effectively.”

The lack of access to Dave makes being one of his personal assistants one of the most appealing jobs on the show. Anyone in a far-flung department who needs a question answered by Letterman knows to go to his assistants now, and not an executive producer. “The problem,” the source says, is that “they’re cut off from the outside world. They only have each other to hang out with. Dave has this very paranoid vision of the world where they shouldn’t be giving information to anybody else and they shouldn’t be associating with anybody else. And so they start to feel very, very loyal, and very trapped. When someone has seven assistants, each one of them does one thing. One presses the red button, one presses the green button, one presses the yellow button.”

Stephanie Birkitt joined the Late Show in 1996, first as an intern and later as an assistant to Letterman. With her sharp wit and unaffected manner, she fit the mold of the kind of girl he felt comfortable around. “She was smart,” says a source who knows her. “And she didn’t have any sense that this was the greatest thing in the universe and we’re doing God’s work here.” She was a hard worker and a go-getter, eager to appear on the air in whatever wacky capacity the show needed. (Within a day of Letterman’s announcement, people were YouTubing videos of Birkitt’s appearances on the show and scouring them for hints of the affair.) Birkitt “liked being part of a team,” says the source. “The job was her social life as well. She was one of the people you saw more frequently.” Birkitt, the source says, wasn’t “this vixen, slutty, hitting-on-your-husband kind of girl. She never dressed or acted inappropriately.” But after a while, there were rumors that Dave used to get in the car at the end of the night and say uptown or downtown. Downtown meant his loft in Tribeca. Uptown would mean Birkitt’s.

At home in Westchester on Friday, the day after his confession, Letterman was already reconsidering his pledge not to talk about the matter again. He’d been on the phone with several members of his staff and learned what his confession was doing to people at the show. “We had tabloid media offering $1,500 bribes to our security guards for access to any floor in the building,” a Late Show source says. “We had reporters chasing staff members to their cars.” Female staffers were getting called by reporters and asked if they’d ever slept with Dave. The problem, he realized, was the open-ended way he’d confessed. Not naming names may have been the only way to play it on Thursday night. But it inevitably raised more questions. Which women? How many? And, in the case of Birkitt, was the relationship still going on?

When Letterman spoke to a staffer on Sunday night, he hadn’t decided what to do on Monday’s show. “We kind of chatted about, ‘Do we address this on Monday’s show, do we not?’ ” says the staffer. “Dave said that he thought that he might want to say something about it.” No one who talked to him Sunday remembers him specifically saying he also wanted to apologize to his wife. By the time he spoke to his contact at Rubenstein, his mind was made up. He would talk about it again. The question then was what, exactly, to say. Would Dave be funny about it, or serious? “We kind of thought, Do we do jokes, do we not do jokes?” the staffer says. “And then we thought, I think we’ve got to do jokes about it.”

Letterman arrived at work Monday morning with a stack of jokes waiting for him—each one about him being in the doghouse. His car’s navigation lady wasn’t talking to him; he’d give anything right now to be hiking on the Appalachian Trail; he spent the weekend raking his hate mail. The question then became how many jokes to use, and whether to let this subject take over the whole show. “I think he really wanted them to be the right kind of jokes,” says a staffer (a Top Ten list about it had already been nixed). At the regular daily monologue meeting in Dave’s office, the writers presented the jokes, as well as others about other topics. But as the writers and Dave mapped out the monologue, “transitioning onto other subjects seemed impossible,” a source says. “The other jokes just didn’t seem to belong.” The head writers, Justin and Eric Stangel, showed him some pretaped bits to use at the end of the monologue, as they do most nights, “but nothing seemed to fit,” a source says. Dave decided to go straight to a commercial after the last joke. Eventually, the entire fifteen-joke monologue (not counting a quick cutaway to a sneezing monkey) would be about his personal mess, starting with that brilliant, seemingly off-the-cuff intro: “Did your weekend just fly by?”

What Halderman hadn’t counted on was that the self-loathing side of Letterman won out. It always does.

But Dave wasn’t satisfied with just the jokes. In his dressing room before the Monday taping, a source says, Dave told a handful of writers and producers that once again, he’d be talking about the alleged blackmailing at his desk after the first commercial break. The producers and writers cleared out, and Dave sat in his dressing room with a pad of paper, handwriting his notes.

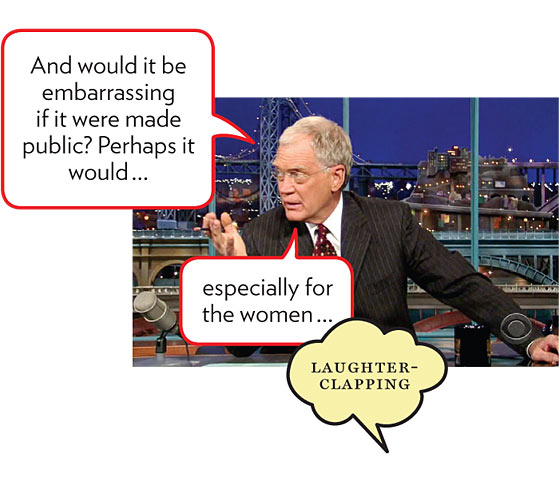

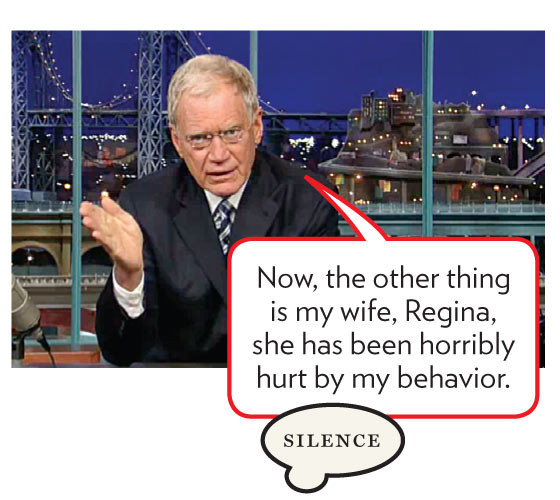

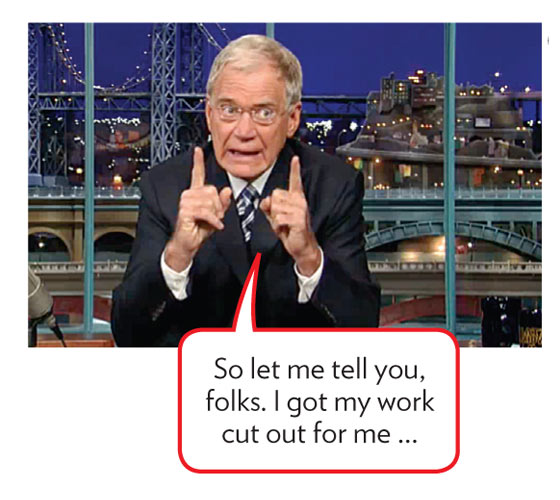

On the air, after the first break, Dave said that his sexual relationships with staffers were in the past, and apologized to the people who worked on the show. “I’m terribly sorry that I put the staff in that position,” he said. “Inadvertently, I just wasn’t thinking ahead.” Then, with rare earnestness, he talked about Regina. “She has been horribly hurt by my behavior, and when something happens like that, if you hurt a person and it’s your responsibility, you try to fix it. And at that point, there’s only two things that can happen: Either you’re going to make some progress and get it fixed, or you’re going to fall short and perhaps not get it fixed. So let me tell you, folks—I got my work cut out for me.” For the first time in the whole sordid business, Dave didn’t get a laugh.

Even before Monday’s show aired, Joe Halderman and his attorney had begun mobilizing. By Friday, Halderman, a 51-year-old producer for CBS News’ 48 Hours, had been identified as the alleged extortionist. Halderman, who had lived with Birkitt for several years, was said to be jilted, desperate for money, or both. At Halderman’s arraignment on Friday, his attorney, Gerald Shargel, told reporters that the story Dave told on television the night before wasn’t the whole story. He didn’t give specifics but suggested there would be more revelations to come.

On the Monday morning talk-show circuit, Shargel said it was absurd to believe that Halderman would ever try to extort someone and accept a check. He also told the Times that day that he has evidence of sexual harassment that he will share “in a court room.” (He had a boost from the front page of Sunday’s Post, which breathlessly described Dave’s “restricted office” with a foldout couch and a kitchen—“all the trimmings for a bachelor on the prowl.”) On Tuesday, reports surfaced that Birkitt and Letterman had gone hiking in Montana, and that she told Halderman she was Dave’s best friend, and that Letterman tried to keep her on the payroll during law school and offered her a job as his lawyer once she graduated. The next day, a blind source told the Post, “This wasn’t about money, not money alone. This was revenge. It was about making Letterman miserable.”

Then came a bombshell from a friend of Halderman’s, TV medical correspondent Dr. Bob Arnot, who appeared on Thursday’s Good Morning America and supplied the world with the image of Joe discovering Letterman and Birkitt in “very passionate embrace” in Dave’s car one night in August—a scene that, if true, suggests not everything ended between the two when Letterman said it did. To beat the extortion charge, Halderman and Shargel apparently aimed to convince people that Halderman wasn’t after money; he was simply a jealous lover seeking revenge. They also intended to dish enough dirt about Letterman to persuade him to agree to drop the charges against Halderman. On Thursday, Shargel told the Times, “This is not a parlor game. My client is facing fifteen years in jail. If Letterman gets muddied up, so be it.”

Inside the Ed Sullivan Theater, the staff is gossiping. “Of course everyone is sitting around going, ‘I wonder who else he’s sleeping with?’ They play the game—‘Do you think he did this? Do you think he did that?’ ” says one source. People talk about Birkitt, who is on paid leave. “They’re all like, ‘My God, how much was she making?’ And they’re saying she wasn’t even at work for a couple of years while she was at law school—how much was she being paid at that time? They didn’t think about it at the time because it wasn’t an issue. Now that it comes out that they had a relationship all that time, they’re thinking about it.” (A spokesman for the Late Show has said that Birkitt worked part-time while at law school, and paid her tuition in part with a loan that has since been repaid.)

Some staffers say Dave should have spared everyone the trouble and just paid Joe. “Some people are thinking, ‘Aw, man, I can’t believe Dave did this to us. We were just winning in the ratings, we were really doing good, and he had to come out and make this a pissing match between him and Joe?’ ” says the source. At the same time, “There’s this circling-the-wagons mentality of everyone who worked there,” the source says. “It’s like a kid saying, ‘People are saying bad things about my daddy.’ ”

Others are focused on whether Letterman is artistically compromised. “Does it affect his ability to make a joke about President Clinton or whoever it’s going to be?” says Burnett. “I guess we’ll have to see. But if the trade-off here is Dave navigating his way through that in his own unique way, I’ll take that over just another Bill Clinton joke every time.”

Birkitt has been scrupulously silent. She is said to be mortified by what has happened—both the extortion attempt, which she is said to have known nothing about, and the revelation of the affair. “Joe is an adult. Dave brought this on himself,” says a source who knows all three people. “Stephanie is the sweetest girl. She’s the one who is going to get damaged, and that’s not fair.”

Competing images have emerged of Halderman—courageous, award-winning newsman; desperate, spurned lover; and conniving mercenary. They may all be true. “Those aren’t mutually exclusive,” says one source who knows Halderman. “You can be a great journalist and a lowlife frat boy.” If all Halderman wanted was to embarrass Letterman, observers have wondered, why ask for the $2 million? Why not simply come forward with the evidence of Letterman’s affairs? The answer, perhaps, is that Halderman believed this was a perfect crime—that Letterman was such a recluse, so private, so invested in his image, that he would never allow the revelations about Birkitt to become public. But what Halderman hadn’t counted on was that the other side of Letterman, the self-loathing Letterman, won out. It always does. “Dave is like, ‘No one fucks with me. You fuck with me, you die,’ ” says a source. “All Dave cares about is his career.” At home in Norwalk, having posted $200,000 bail, Halderman is awaiting his next court date.

No one knows what’s going on between Dave and Regina. It remains unclear when she knew about Stephanie or any of Dave’s affairs. Regina had left Letterman’s show long before Stephanie worked for him, but she knew her well; Stephanie reportedly accompanied the family on vacations. One source says Regina had every reason to believe that Dave and Stephanie had always been just friends. Stephanie would talk at length with her Late Show friends about Joe Halderman. “She was really into him,” the source says. “She was very much in love with Joe.” She was blending into Halderman’s complicated family, his two children from a past marriage. That attachment, a source says, made her less threatening to Regina. “Stephanie was someone she trusted,” the source continues. “I’m sure Dave’s wife felt some comfort because Stephanie lived with her boyfriend that she was clearly over the moon for. I think Regina let down her guard. You have to know Stephanie. She just doesn’t seem like the kind of person who’d be sneaking around with your husband behind your back.”

Before going on a one-week production break last week, Letterman was apparently doing his best to keep to a normal routine. One source says he has told producers that whatever happens, he’s confident he did the right thing by not giving in to Halderman. All he can do now is hope that Shargel is bluffing and that the worst is behind him. The most likely outcome of the legal proceedings is that Letterman will allow the D.A. to drop or reduce the charges to avoid a trial and the fresh publicity explosion it would trigger.

Letterman also has his legacy to worry about. Dave has always been both a mammoth talent and a force of self-destruction. For most of his professional life, his darker nature helped create his beloved public image. But if self-loathing was his tragic flaw, then his affairs with assistants on the show may prove to be his denouement. Back in 1982, when Late Night started, Dave told profile writer Bill Zehme his theory of late-night talk-show success: “The reason The Tonight Show succeeds is because people like him,” Letterman said. “They turn on the show to see Johnny. Hopefully that will happen here.”

In that same story, a comedian and close friend of Dave’s agreed. “There’s no hypocrisy in what he does,” Jay Leno said about Dave. “I think he tends to lead his life exactly the same way he behaves on television.”