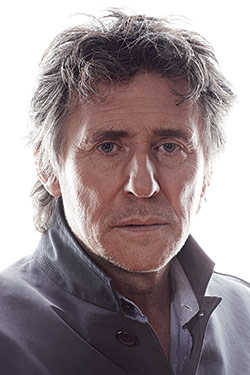

It’s the most natural thing in the world to smile,” says Gabriel Byrne, frowning at an array of Gabriel Byrnes—digital photos shot moments before. “It’s the most unnatural thing to fake a smile.” He gazes at the screen for a good long time. As he walks away, he asks, “Is there anything worse than looking at your own face?”

It’s a cold fall afternoon as we stroll from the studio to the Angelika cinema’s café. Byrne and I chat about the peculiar immediacy of modern technology, how it both deforms and expands identity. He tried Twitter for a full two hours, he tells me, before his daughter, Romy (one of his two children with ex-wife Ellen Barkin), made him stop. His first tweet: “Regret not the past, fear not the future. Percy B. Shelley.”

Still, it’s clear Byrne’s heart beats faster for older styles of communication. He cherishes his fountain pen. He adored a recent visit to Governors Island: silence, no cars allowed. He marvels at the sweetness of early photography, when people posed with “a stiltedness and an awkwardness and a shyness.” In the eighties, when he lived in London, Byrne collected hand-embroidered postcards from World War I. “In the banalities people wrote to each other, there were all kinds of stories,” he says, and performs a lilting imitation: “We’re having a fine time here at Tremore. Gertie says she feels better today. The sea air is doing her good, I’m sure. Well, that’s all for now.”

In their pith and semi-public display, he points out, postcards might be the grandfather of Twitter. “And of course, there were the ones that flighty girls could send to timorous men,” he adds, using his hands to draw a postcard in the air, one designed so a woman could press her lipstick to an outline. “If you were a man receiving that, it must have been highly erotic.” He smiles. “That’s one thing you can’t get with Twitter.”

At 60, Byrne—an Irish-born actor best known for Miller’s Crossing and The Usual Suspects—is dashing in a dark-blue coat and burgundy cravat. With his shaggy hair and fans of laugh lines, he can come across as a schoolgirl’s fantasy of a Byronic professor, or perhaps a particularly literary rock star. He wears a Claddagh ring, the heart pointed inward. He speaks fluently and fluidly. He presses his hands between his knees, smiles crookedly, quotes poetry. It’s not difficult to comprehend why, when I search his own name on Twitter, I find strangers posting about stalking the man through the streets of New York.

Part of this allure, of course, derives from what has become his signature role, Dr. Paul Weston, the analytic hero of the HBO series In Treatment, now in its third season. The show, based on an Israeli series (see here), is one of the most subtly experimental dramas on television, using Byrne’s sooty charisma to tremendous effect. In Treatment consists of little but dialogue yet manages to be as suspenseful as 24, romantic and agitating in surprising turns. The third season features three new patients: an Indian widower (Slumdog Millionaire’s Irrfan Khan), a narcissistic actress (Debra Winger), and an acerbic gay teenager (Dane DeHaan). The first dozen episodes blew me away.

Still, all that listening is a brutal weight for an actor. The show runs in two-day sequences, with two episodes each night. During the first three, Paul wrestles with the angel of other people’s suffering—alternately challenging his patients, soothing them, and riding the flow of transference. On the fourth, the episode devoted to Paul’s sessions with his new therapist (Amy Ryan), Dr. Weston becomes himself again: an uglier and smaller man. He is depressive, rancorous, sardonic; he rages paranoically against his own mortality. Over the show’s three seasons, the character has gone through a divorce, his father has died, and he’s left his original therapist (Dianne Wiest). Where most shows either celebrate therapy (à la Tell Me You Love Me) or damn it (as The Sopranos did very effectively by the series finale), In Treatment takes an original approach. Never coming down on one side or another, neither glamorizing nor demonizing, the series turns its structural conceit—a quartet of theatrical, seductive, repetitive conversations—into a near-musical meditation, exploring a greater existential theme: What kind of relationship is this?

“It’s a very hard thing to constantly listen,” Byrne says of the role. “To really listen. I mean, what do you go to therapy for? I suppose you go so you can actually face who you really are. To be in a room that’s sacred, in that what’s said there can never be really used against you. You’re in a relationship of absolute trust where you are removing the mask. It must be wonderfully liberating.”

And yet Byrne doesn’t go to therapy himself—and never has. I ask him why this is, given that he’s been open about his own struggles, including depression and years of binge drinking. He grew up poor in Ireland, the son of a cooper and a nurse. Earlier this year, he spoke about having been molested, when, as a vulnerable boy, he was sent to a seminary to train for the priesthood. (He has mixed feelings about having spoken out about this experience, but says he did so to help reduce the shame and silence for others. “Those scars are still there, but at least I recognize them now. And know where the pain is coming from, whereas for a long time I didn’t.”)

“I don’t really know the answer to that,” he says after a long pause. “I tend to talk to friends. You can learn so much from what your friends say—and don’t say. I think women are better at cultural support, at getting together and rabbiting on about anything and everything. It’s more difficult for men to reveal their vulnerability.” He is no longer a believing Catholic and considers himself an atheist. “I could be wrong in that I haven’t gone to therapy. As I said, I really do admire the profession—I just don’t know how I would go about finding one.”

I tell him I admire the way the series dramatizes one of the odder aspects of analysis: the way therapy itself is a form of performance.

“Yes, I’m much more interested in the psychotherapist as actor than in the actor as psychotherapist,” says Byrne eagerly. “People will say to you sometimes, ‘Acting! How do you do that? It’s a really difficult job.’ But the reality is, we act all the time. True individual moments of intimacy throughout the day, when are they? So when a man is in a chair and he has to listen to somebody else’s story—I often wonder how much of that story we take on.”

Byrne describes a funeral he attended in Florida. He found himself speaking to the woman whose job it was to show loved ones the funeral plots. The cheapness of the system outraged him, its callous pretense, the $5 required for an extra folding chair for an elderly guest. “My God! Do you know that you have to pay $45 to have your loved one’s hair combed? Unbelievable. It was one of the most—this is the thing …”

He pauses, then collects himself and comes to the subject we were skirting earlier. “This is the thing I have a problem with. Can you pay for true empathy? True intimacy, true empathy, true compassion. I have a problem saying, ‘Can I pay for that?’ Should I pay for that? Shouldn’t I be finding those things in my life with people I know? Maybe that’s why I haven’t gone to therapy.”

The funeral worker drove Byrne through the Florida plots in a golf cart. “She was telling me about the value of underground real estate,” he says, with faint disgust. “Which is what graveyards actually are. And she—acted. You know, what’s meant to be the most real moment in life.” Byrne asked the woman if she brought the work home. She said simply, “No. When it comes to five o’clock I go home.”

Byrne longs for something more primal, more genuine, something he remembers well from his own childhood: the raucous, weeping, singing traditional Irish wake, where the presence of the dead body is not sanitized. “Because by looking at the body, you’re looking at your own life. You’re looking at the absence. And the ritual was there for a purpose. And what it was saying was: ‘You have life. So live life.’ ”