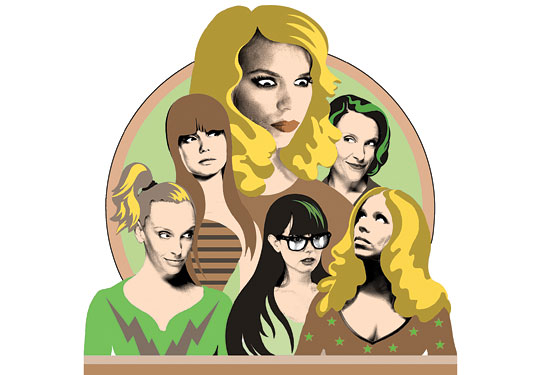

When the final season of The L Word kicked off with Jenny Schecter floating in a West Hollywood swimming pool, it wasn’t exactly a shocker. Anyone might want to kill her. With her Lulu bangs and penchant for manatee erotica and that lunatic raped-by-Hasids backstory, Jenny (as embodied by goth pixie Mia Kirshner) was an exhibitionist for our age, whose presence managed to turn the once-diverse ensemble drama into a one-woman show. As she morphed from memoirist to stripper to auteur, seducing her critics’ lovers, killing dogs, and occasionally drifting out to sea, Jenny drove viewers, and her fellow characters, nuts, but she was also a terrific, messy TV creation: the female basket case as truth-telling catalyst.

I’d say that I’ll miss ol’ Jenny, except that I can see that she and her like will not be killed so easily. In the past decade, a sisterhood of unbalanced femininity has replicated across the cable landscape, with a few early soul sisters on HBO, like Six Feet Under’s sex-addict Brenda (at least until she straightened out) and Big Love’s prairie-dress wackadoos Wanda, Lois, and Rhonda. Quality cable, especially HBO in its heyday, operated for so many years as an in-depth investigation into masculine angst, with The Sopranos, Deadwood, Six Feet Under, The Wire, Rome, Entourage, and The Mind of the Married Man all exploring what made a man a man and what made him a monster (no wonder HBO turned down Mad Men, worrying that it was more of the same).

Now it seems that the era of the outrageous outsider chick may be upon us, in her various manifestations as protofeminist rule-breaker and shit-stirring catalyst, with subcategories of sex-rebel, crazy lady, and artist. On Showtime, in addition to The L Word, there’s also Secret Diary of a Call Girl and now United States of Tara, in which suburban mom Tara (Toni Collette) splits into a teen hussy, a redneck dude, and Martha Stewart. What each of these series share is a fascination with femininity as a vaudeville act—a daffy exhibition of artificial selves. It’s as if everyone at the channel was bingeing on the books The Madwoman in the Attic and Gender Trouble, with study breaks to mosh to Courtney Love.

Secret Diary of a Call Girl, now in its second season on Showtime, is based on the pseudonymous blog of Belle du Jour, a “high-class” London hooker. During its first year, the series so glamorized its protagonist it was practically a recruitment video. An independent sex worker with a sociological bent, Belle makes it clear she’s never been molested or otherwise traumatized: She turns tricks because she loves the job—not just for the sex (though her clients are a suspiciously attractive crowd) but for the thrill of standing outside the games normals play. Though Belle knows others view her as pathological, and that occasionally worries her, she also gets off on it: She’ll never make the bad bargains other women make because hers are always literal and lucrative.

The show is a true guilty pleasure, with that classic cable-TV meld of glossy production values and shocker blow-job sequences. The writing is witty, and as Kirshner did with Jenny, Billie Piper salvages a character who might be unbearable in other hands: drily self-deprecating and sexy in a goofy, almost sloppy way, all smashed-potato features and smeary glitter eye shadow. In its second season, the show questions the divide between artificial and genuine intimacy, giving Belle an unstable protégée as well as a “real” boyfriend. In an early episode, she is confronted by the wife of one of her clients, to whom she can’t quite explain that she is not in fact her client’s girlfriend, but rather “the girlfriend experience,” or GFE. Her client doesn’t quite get the distinction, either, and so Belle endlessly struggles to sort out the levels of artifice her chosen profession depends on.

But really, all of these series are about the GFE. They’re centered—anxiously, enthusiastically, at times incoherently—around the idea that acting like a woman, even a “normal” woman, is a set of decorative choices, disguises which may be fun or tormenting, depending on the woman. As in Tilda’s Swinton’s old 1996 film Female Perversions, in these shows, men may have fetishes, but women are fetishes, painting themselves into cartoons and marveling at the effect.

This is true in a different way on United States of Tara, a flawed but fascinating series about a women with Dissociative Identity Disorder, formerly known as Multiple Personality Disorder—and previously a television staple, mostly appearing on gimmicky legal procedurals. As with Secret Diary, there’s a didactic undercurrent to Tara (written by Juno creator Diablo Cody) that nearly derails the whole thing. Tara’s condition is not something bad or sick, the series insists with a slightly grating preachiness. If Tara sometimes pulls on a mask, becoming a more extreme “alter” under times of stress, well, hey, that’s just a coping mechanism, worthy of sympathy and acceptance—part of the continuum of human experience. “Do you like being different?” Tara prompts her gay teenage son, and of course, he agrees with his mother: “I love it.”

But would any teenager really feel that way? The show is resolutely wacky, but it is clearly also intended to be about real and sometimes painful feelings. In the show’s opening episodes, Tara’s teen kids aren’t simply resigned to their mother’s situation, they’re her cheerleaders—cringeworthy wish-fulfillment that makes these scenes nearly unwatchable. Then slowly, as Collette’s nuanced performance kicks in, refreshing ambiguities start to soak through, including an acknowledgment that she’s lost whole regions of her own experience. At its best, Tara can feel like a sister to Showtime’s Dexter: a heightened allegory for a woman’s struggle to reconcile her own frightening sensations of vulnerability, desire, and aggression.

It’s an intriguing theme, and it would be wonderful if it pays off. But like The L Word, in which the once-juicy soap-opera plot has become a series of ineffective shocks, and Weeds, featuring another appealing but frustratingly inconsistent outsider-heroine, Showtime’s series have borderline personalities. They’re charismatic; they’re unpredictable. Yet there’s also something grotesque and manipulative in the mix. When HBO series fail, it’s most often because they are too ambitious—pretentious, arty, overreaching. For all the good writing and fabulous actresses, at their worst, Showtime can make you feel like a sucker or a cynic, someone who longed for the girlfriend experience and found instead a bag of practiced tricks.

United States of Tara

Showtime.

Sundays at 10 p.m.