I’m crouched in a dining room in Washington Heights, watching a man get ready to masturbate. Louis C.K., the stand-up comic who is the star and creator of the FX sitcom Louie, slumps in an orange lounge chair. His knees are spread, his pants pushed down to his ankles. With his laptop propped open, he mimes the requisite jerky motions below his waist, rolling his head from side to side. The camera rolls with him, making Louis’s image bob like a cork on a wave.

It’s a surreal effect that Louis C.K. (short for Szekely) has been experimenting with, although so far he’s not sure if it will come across as funny or just strange. Still, the shoot’s going well. Later, he’ll edit in other scenes, sequences in which the sexual fantasy goes crazily awry: The hot woman he’s fixated on will make anatomically impossible sexual demands; a bystander will chime in; and eventually, Louie will resort to fantasizing about an old favorite, a TV actress from the seventies. (They need to contact her people for permission to use her name, Louis tells me during a break.)

After he calls “cut,” Louis tugs up his pants and uses the same laptop to watch clips of actresses auditioning to play the woman in his fantasy, as crew members circle around him, adjusting the lights. “She’s completely wrong,” he tells his executive producer, Blair Breard, snapping one window shut. Another is a “walking orgasm,” but not funny. He laughs at an elderly man’s line-reading of “American women are very liberated.” Now and then he glances up, offering brief commands. “Stop messing with the lighting,” he says. “It’s fine! Come on. You’ve got something good here.”

Television showrunners are notorious multitaskers, with the most successful able to toggle easily between the roles of CEO and auteur. But Louis’s work on Louie requires a whole different level of personal oversight. The show is based on his life. Louis is the director. He’s also the only writer, the sole editor (he no longer shares duties with the co-editor he had last season), not to mention the person who oversees music (when the music guy’s budget ran out, he decided to do it himself). He also hired his own casting team: Last season, he turned down FX’s offer to help out and doesn’t inform them about casting in advance. But perhaps the most unusual aspect of the show is that Louis C.K. gets no notes from the network during filming, no script approval—an unheard-of “Louis C.K. deal” that has made him the envy of comics and TV writers alike. It’s a situation Louis is not taking for granted.

“No one on the planet Earth has what I have right now,” he says in his trademark tone—a deadpan delivery that somehow manages to sound at once bleak and exhilarated. “No one ever has. And I don’t know that I ever will again.”

Like HBO and Showtime before it, FX has spent the past few seasons branding itself as a cable channel. This season, it’s canceled two excellent but low-rated dramas—Terriers and Lights Out—and won attention for a third, Justified. But the network’s greatest success has been with comedies. There’s It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, an anarchic ensemble now in its sixth season. There’s Archer, an animated satire of James Bond masculinity, and The League, a shaggy-dude ensemble. And finally, there’s Louie, which amounts to a radical experiment with TV production, one that, unlike the majority of radical television experiments, has not only completed one season but also been renewed for a second. (The season premiere airs June 23.)

Louie is part of a wave of innovation in TV comedy, with writers who aim to explode the sitcom in much the same way The Wire blew up the police procedural. And yet the series—which won critical raves and the requisite tiny cabal of super-fans—differs in one major respect from fast-talking peers like 30 Rock, Community, and Parks and Recreation (on which Louis appeared). Those shows are the product of the traditional sitcom-production technique of spitballing collaboration, with competitive writers’ rooms and improv-ready ensembles. Louie is the sitcom passed through a narrow and powerful prism—the itchy, irascible brain of Louis C.K.

Like the show’s creator, Louie’s protagonist is a recently divorced father of two, a comic who does stand-up at the Comedy Cellar and Carolines. The episodes are punctuated by excerpts of these outrageous club routines, the same ones that have made Louis C.K. a sellout headliner. It’s a role that might sound familiar, given the current rash of rancorous divorced men on television, on Curb Your Enthusiasm, Hung, Californication, and Men of a Certain Age. Louie also has clear antecedents in comic-centered sitcoms from Roseanne to Seinfeld. And yet the series, which is scored to jazz, with black-and-white imagery and a surreal spirit, feels like nothing else on TV. At times, it suggests early Woody Allen with a scatological streak. Episodes glide unexpectedly from filthy to poignant, alternately cinematic and what Louis calls “balls funny.” There’s little continuity: In one episode, Louie’s mother is a narcissist; in another, a nurturer. Louis himself is the continuity: his jittery consciousness, floating through the aftermath of divorce, which operates as a kind of second adolescence, this time complicated by kids and the fear of death.

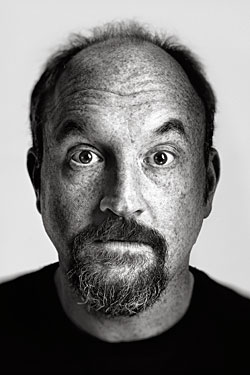

The fictional Louie has a serious Charlie Brown streak. He’s awkward with women; he stares gloomily down at his jiggling belly. In person, however, the nonfiction Louis C.K. is an attractive man in his early forties, built square, with pale brown eyes and a neatly trimmed goatee. He carries himself with physical confidence (a few years back, he trained with boxer Micky Ward, whom he knows from his hometown of Lowell, Massachusetts). He is not warm, but he is smart and direct. He answers questions in a lucid flood but doesn’t ask much back. Every once in a while, he grins, and when he does, his face softens and lights up, his eyes twinkling.

After the masturbation shoot ends, we go downstairs, where his new show assistant—the first he’s ever hired—is waiting. It’s her first day. (She’ll be let go within a month.) “Did you do the thing with the car?” he asks her, and she nods, smiles, hands him his keys.

We get into his Infiniti and head down the West Side Highway, toward his apartment. As he drives, Louis describes his influences, which include oddball films like Robert Downey Sr.’s surreal Putney Swope, as well as What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, which Louis tells me nearly wrecked its director in the making. Films like this gave him a naïve impression of how Hollywood worked, how far you could go, how strange you could be. And historically, it’s been even more difficult to make something original on television, where the default is compromise.

“Everybody wants to improve the material, so they will comb over it, take out abnormalities,” he says of the traditional writers’ room. “It’s like certain kinds of food: You like them to be chunky and irregular. And they’ll just keeping puréeing and puréeing till it’s perfect, and who the fuck wants it?”

Not surprisingly, this is a philosophy based on years in the purée mines. After an early childhood spent in Mexico City (his father is a Mexican-Hungarian economist, his mother an Irish-American computer programmer), Louis moved to Massachusetts; when his parents divorced, his mom raised Louis and three siblings on her own. He worked as an auto mechanic before trying stand-up, at 19, in Boston’s thriving open-mike scene. On Marc Maron’s WTF Podcast, a cult outlet for comics, Maron and Louis—former best friends who have since lost touch, in part due to Maron’s envy—reminisced about their early twenties. From Louis’s account, these years seem to have consisted of bold comedic breakthroughs broken up by financially irresponsible binges. He ruined his credit when he bought a car on his Visa card; he lived in an apartment so slovenly he didn’t clean up a shattered steak-sauce bottle for months. (I ask him about whether he and Maron are back in touch after years of estrangement, and he says they are, now and then. “I tell him I’m happy to sit down anytime for a real conversation, but he just wants me to do the podcast again. It’s a little weird.”)

In his early thirties, he directed short black-and-white films with his ex-wife, painter Alix Bailey. (He’s uploaded many of these to YouTube.) But he also made a living in the writers’ rooms he now decries, ginning up jokes for Letterman, Conan, and Chris Rock. In 1996, he was the head writer for The Dana Carvey Show, where he wrote a notorious opening sketch that poked fun at the feel-your-pain empathy of Bill Clinton, in which the president breast-fed the nation, squirting milk out of a line of dog’s nipples. The show was canceled after six episodes.

Along the way, Louis honed his stand-up act, moving from surrealistic wordplay to a more confessional approach. He became a role model to other comics—one of the rare “alternative” comics to gain mainstream success, famous for generating material at a radical pace (he trashes his entire hourlong set after each special). He has memorable riffs about race, about sex, and about politics; a rant about technology called “Everything’s Amazing and Nobody’s Happy” went viral. And he has become a particular fascination to parents for his cathartic routines on the existential aspects—the grossness, boredom, and rage—that accompany raising kids. “When you first get married, you have a relationship that’s so important to you, and you’re working on it together,” he explains in one routine, which he performed while he was still married. “But then you have a kid. And you look at the kid and you go, ‘Holy shit, this is my child! She has my DNA, my name. I would die for her.’ ” He takes a short, killer pause. “And you look at your spouse and you go, ‘Who the fuck are you? You’re a stranger. Why do I take shit from you?’ ”

And yet, every attempt he’s made to get this sensibility on film has failed. A 1998 black-and-white indie called Tomorrow Night aired at Sundance but went nowhere. Pootie Tang, his absurdist hip-hop comedy from 2001, crashed when the studio stepped in and reedited material he was already struggling to complete. Lucky Louie, an arch take on The Honeymooners, was canceled after twelve episodes on HBO in 2006. In the aftermath of that, he was hesitant to commit to another TV deal. But following a sold-out show in Los Angeles, offers began pouring in again, the numbers ratcheting upward. Then at a meeting Louis nearly decided not to attend, John Landgraf, the president of FX, offered him $250,000 to make a series about his life, a number that included Louis’s salary. “I thought, I’m too fucking old to stand in the cold with a young crew—and I’m just gonna go through the same shit for less money.” But Landgraf impressed Louis, pitching a model designed to keep shows “pure.” “I said, ‘Okay, the only way I’m doing this is if you literally wire the $200K to me and I go to New York and just make it. I don’t gotta tell you what it’s about. I don’t know what it’s about.’ ”

Louis’s manager promised he could bump up the number to $350,000, but Landgraf called Louis directly. To get more money, he explained, he’d need to call Rupert Murdoch. And Louis would have to take network notes. “I called my manager and said, ‘Shut your fucking mouth!,’ ” recalls Louis, laughing.

The thirteen episodes he produced swerved radically in tone and style. One takes place during the week Louie’s ex has custody: He falls into a wormhole of self-indulgence, binging on ice cream, getting stoned with a neighbor, and watching a water bottle tumble five stories onto a car. Another is an extended flashback to a Catholic-school trauma (the kids are forced to nail Christ to the cross). In the episode that made me a convert, Pamela Adlon—the burr-voiced actress whom Louis calls, with amazement, “the only real comic collaborator I’ve ever had”—shrugs off his come-ons at a wintry New York playground. Instead, the two single parents trade increasingly lurid suggestions about other parents to hit on: “Look at her. I bet she’d suck your dick just to break the awful pattern of her life.”

“No one on Earth has what I have right now. And I don’t know that I ever will again.”

These episodes weren’t written as traditional scripts. Instead, according to his producer, Breard, Louis produces write-ups for sketches, then films out of sequence, often without an exact sense of where each scene will go. As the airdate approaches, Louis edits episodes in his living room or sometimes in a coffee shop, using music as glue. His goal, he tells me, is a first-draft sensibility, in which jokes show their seams. “I’ve seen how much he’s grown over time as an artist,” says Breard, a close friend who first worked with him when he made Pootie Tang. “He’s confident in his choices. And there’s a real humanity, a gentleness in what he’s saying. It’s never gratuitous; it’s coming from a humanistic POV.”

Even back in his twenties, Louis had fantasies about the potential for independent TV. “You know, the people who do indie film and decide who gets those little budgets? They’re mean, man. They’re cold and very cool-oriented.” TV in general “has lower self-esteem, so there isn’t this lofty sense of ‘We’re all C. B. DeMille.’”

He doesn’t watch much television other than boxing and news, but he’s willing to throw off some fairly caustic opinions about other sitcoms. “Yeah, I can’t stand that shit,” he tells me about 30 Rock and Community. A few minutes later, he acknowledges: “To be honest, I’ve only ever watched part of one episode of 30 Rock.” It’s not the quality of network sitcoms he objects to, he explains; it’s the antic energy he can’t take: the machine gun of polished bits. Although he’s a fan of Family Guy (he watches it at bedtime, since he’s too anxious to fall asleep in a dark room), most self-referential comedy gives him welts. He recalls a recent promo for 30 Rock in which Tina Fey makes a joke about another NBC star, Steve Carell. “What are you doing?” he cries out. “Why are y’all talking about each other? It’s crazy. I think Tina’s really funny, but they get to this place where it gets really madcap, and I just smell a roomful of writers getting off.” He knows how this sounds: “totally bigoted, it’s obnoxious.” But he adds, “I think a lot of my feelings about this have to do with having lived in that world for too long.”

Then again, one-man production has its own pressures—ones he describes with a mix of braggadocio and anxiety. “I have a huge abyss I’m staring into. We have stuff to shoot for another two or three weeks, and then there’s just nothing.” That’s seven episodes unwritten—not to mention the difficulties of acting and directing simultaneously. “Sometimes, right before we start shooting something big, I get an awful pit in my stomach because I know it will be hard. And then I’m in it and I’m so— ” He suddenly beams, goes rapt, his cautious expression lifted off like a mask. “And then it’s done and I go, ‘Jesus fucking Christ, I’m exhausted.’ ”

Even if the second season hits every one of its goals, he tells me, it guarantees nothing for the future. At HBO, he learned how much his survival was contingent on his patrons—executives like Chris Albrecht, who signed off on “an ATM of projects” until he resigned in 2007 after a domestic-violence scandal, and now FX’s Landgraf, about whom he says, “I want to make him some money.”

After Louis signed, Landgraf sent him DVDs of The Shield, FX’s celebrated cop drama. Louis promptly began to procrastinate. “I was supposed to be writing, and instead I just lived for The Shield,” binge-watching seven seasons, marveling at the deep story arcs, the unforgettable performances. During the years it aired, The Shield’s creators were “like the Beatles” to their small set of fans, he says. “And it’s all gone now! Michael Chiklis is back to being a monster. The guy who played Wagenbach? I’ve never seen him again. That’s perfect success for a show. And it’s gone. Now they are back to trying to pay their rent.”

We stop at a red light. He turns and looks me in the eye. “That’s not bad news. That’s just realistic.”

We pull up to his Upper West Side apartment—a swanky place he rented, he explains, through a series of savvy negotiations during the economic crash. It’s big enough for his daughters, who are 6 and 9, to scooter in, with an area for them to perform shows. He shows me a sewing machine he got one of his girls for her birthday and holds up a tiny sweater he made using it. “I’m turning my kids’ future into their present,” he explains. “Because all this won’t last.”

He has custody of his daughters for half the week. During those days, he’s entirely off the clock, with no paid child care—a situation that initially caused some tension with his crew. “The marriage is over. But I’m a father with my kids alone. I don’t run errands for their mom anymore. I buy them pillows. Keep them in socks. And I cook for them, I cook all their meals.” (He places this in contrast to his father, who left when Louis was a child: “I imagine he’s seen my show. I haven’t really talked to him about it.”)

The mistake so many parents make, he tells me, is to go into mourning for the life they’ve lost. “All those early bits I did calling my kid an asshole came out of not knowing how to handle it. You distill those feelings in stand-up.” But as his children get older, he says, he’s become more confident about his role—something he wants to incorporate into the show. “They’re amazing now. It’s nice to be with them. It’s delightful. And you know, it also doesn’t last very long.”

I ask what his ex-wife thinks of the show. “I have no idea,” he says. “I haven’t asked her.”

Against a wall there are two guitars. A clarinet lies on the mantelpiece, near Louis’s Emmy for The Chris Rock Show. In the foyer, there’s a metal cabinet filled with pricey cameras—his one vice, he tells me. “To me, art supplies are always okay to buy.” There’s also a desk with three huge monitors on which he edits the series. He pulls up an iTunes playlist and clicks on a theme he describes as “Monkish, Thelonious-y.” We listen together for a minute, the music rising, getting at once sadder and more exciting. “Isn’t that great? And now I’ve got to write a scene that fits it.”

Then he selects a scene with Pamela Adlon. It’s a classic New York real-estate nightmare, with the two haggling with a manic Russian Realtor. Adlon appears in only three episodes this year because she’s tied to Californication. “I’m way behind. It’s terrible,” he says, brooding again about deadlines, about being “stuck in the mud,” as he did last season. He has a cache of “serious e-mails” from Breard, saying, “You’re in a lot of trouble; you need to stop making us wait or we can’t make a show anymore.’ ” (In a phone conversation, Adlon says she’s confident Louis will pull it off, describing him as having “his own kind of discipline. Like a college kid cramming for a final.”)

On the desk I see a pile of note cards. At my request, he picks up the top one. “People are selfish,” he reads, explaining, “This is some stuff I’ve been working at onstage.” On the next he’s written, “I used to live with Hitler.” He glances up. “That’s something I probably can’t do. It was funny when I said it out loud.” Another: “Stocking is nigger brown.” He explains it comes from a stage bit about an elderly aunt who called Brazil nuts “nigger toes”—“and these are people that we love, and they say ‘nigger brown’ and ‘nigger toes,’ and what are you gonna do?” He reads a few more: “Gray’s Papaya” (“they’re very cinematic, and I want to shoot in one”), “I love you” (“That’s for my daughter”), “Anal Sex,” “Planetarium,” “Mom’s Rape,” “Flabby Action Dad,” “Upstate Limo Driver,” “Thomas Jefferson,” and “Scaled” (“I stole many scales from my junior-high school and sold them for pot”).

Finally, Louis picks up a longer card, with sentences printed in black marker. “Human kindness has no reward,” he reads. “You should give to others in every way you see. You should expect absolutely nothing from anyone. It should be your goal to love every human you encounter. All human suffering that you’re aware of and continues without your effort to stop it becomes your crime. Humans are always evolving. If you do one thing that if done by every human would destroy the world, that makes you Hitler.’”

“There’s Hitler again!” he says, then slaps the card down. “I don’t live by any of those. But I believe them all very strongly.”