When the ABC sitcom Happy Endings finished filming its first season, the cast and writers did what any self-respecting sitcom crew would do: They rented a party bus and set course for Vegas. The bus had neon lights and a stripper pole and was outfitted to be a Damn Good Time. It ended up sitting in eight hours of bumper-to-bumper traffic while the cast—who had wrapped at 4 a.m., a mere handful of hours before the party bus departed the Paramount lot—tried with varying degrees of success to cover up the fact that no one really wanted to be going to Vegas. “Everyone was kind of like, ‘What are we doing?’ ” says Casey Wilson, an SNL alum whose character, Penny, is the show’s perpetual optimist. “People were nauseous and sick. Damon [Wayans Jr.] was lying down on the seats with pillows over his eyes trying to sleep. So it wasn’t quite like the party bus that you know and love.”

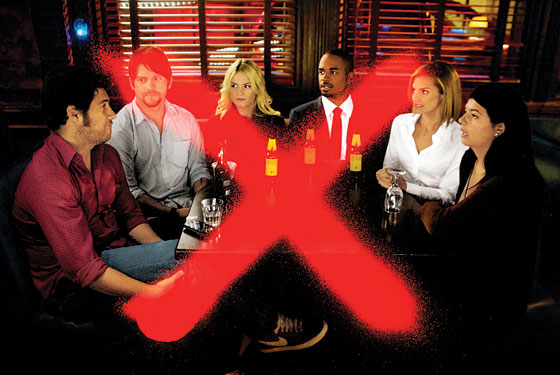

In the way that life can imitate art, the first season of Happy Endings also tried with varying degrees of success to be a Damn Good Time and turned out instead to be an Okay Time With Potential. The key elements were certainly in place—talented writers, esteemed producers, and an enviable cast with a solid improv pedigree. But the show was hemmed in by a premise established in the first two minutes of the pilot, in which Elisha Cuthbert’s character, Alex, leaves Zach Knighton’s character, Dave, at the altar for a guy who glides into the church on Rollerblades, while their four closest friends (played by Wilson, Wayans, Eliza Coupe, and Adam Pally) look on in horror. The setup allowed the audience to delve into an established friendship circle in medias res at a defining moment when the group had to decide whether to splinter. But it also meant that one character was locked into spending a season dealing with the emotional repercussions of having been jilted in a brutal and public fashion (those Rollerblades!) while the other was locked into apologizing for said jilting. What was intended to be an ensemble show ended up being rooted in the two straight-men characters while their more hilarious sidekicks were sidelined. Tellingly, the network aired the two episodes that were meant to follow the pilot—and dealt most directly with the fallout of the ruined wedding—very late in the first season, relying on other episodes to try to hook its audience. The show still managed to pull ahead of the season’s other Friends-type spawn (Perfect Couples, Traffic Light, Mad Love) with little to no network promotion, but the cast and crew didn’t pin their hopes on getting a second season. When they did, “I got shitfaced immediately,” says the show’s creator, David Caspe.

“I bought a new house. Well, my wife bought a house, and I came along with her,” adds executive producer Jonathan Groff.

Regrouping for a second season provided Happy Endings with the opportunity to capitalize on its underdog mentality, what Pally calls “a fuck-you attitude that is very apparent and important to the show. I think it’s let us kind of say, ‘We’re going to do what we do no matter what, because it’s not as if anyone’s watching.’ ” Rather than improve ratings by noticeably changing course (as Parks and Recreation had done after its first season), the cast and crew leaned into the weirdness of their comedy. Coupe and Wayans, who play married couple Jane and Brad turned their characters’ initial overachieving-bobo quirks into a full-blown orgy of neuroses—the second season finds Brad wearing a shirtdress because “Daddy likes a deep tuck,” and Jane stalking a kid she thinks might be her egg-donor baby (in fact the parents didn’t use her egg because they thought she seemed just the kind of crazy who would stalk her egg-donor baby). Wilson gave her singleton an ability to rebound that verges on masochism. And Pally’s gay character, Max, so brilliantly overhauls TV’s go-to flamboyant stereotype that in one episode he slovenly hibernates for the winter, like a bear. “It’s like we’re all kind of sharing a brain, and we’re just like, ‘Yeah, this is the direction [the show] needs to go in,’ and we all pushed it into that direction,” says Coupe. “We’ll come up with stuff together and be like, ‘Let’s do this.’ And sometimes there will be a director who’ll say, ‘Please give us a normal take,’ and we’ll be like, ‘No, we want to do it our way.’ And what’s funny is they’ll cave in.”

Luckily, the studio also followed suit. “Maybe we showed just enough promise in the pilot and in the first few episodes that nobody ever went, like, ‘Whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa’ and sort of freaked us out or made us change course in a way that was inorganic,” Groff says. “To their credit, they left us alone a little bit. They didn’t get nervous or lose sight of what they liked about it originally, and they had confidence that we would get there.”

The largest, and most deliberate, overhaul was allowing Cuthbert’s and Knighton’s characters to develop beyond type. “As long as you give me a joke every few weeks, I’ll be the straight guy,” Cuthbert had originally told the writers. “Let me do a couple of comedy things here and there along the way, and that’s good enough for me.” But once they realized that Cuthbert could be funny, they began incorporating her offscreen behaviors into the script, like her invisible hula-hoop dance, or her Renée Zellweger impression. (“They asked, ‘Can you say anything while you’re doing that Renée?’ And I was like, ‘No, it’s just a look.’ ”) Knighton’s character became the kind of guy who gets an idea—like marriage—in his head and blindly sticks to it, even if it’s clearly not going to end well. Suddenly the show’s most traditional characters were “kind of the craziest people in the group,” he says. And Caspe had assembled the ensemble cast he’d always wanted: “That was really my goal from the beginning. You know, depending on who you ask, people’s favorite character is Max or Penny or Jane or Brad or Dave or Alex. I really am proud of that.”

“The great thing about David Caspe,” explains Coupe, “was that he really just wanted to get the people he thought were the funniest and then have them fit into the part, as opposed to the people who could do the part the best.” This made for characters that needed time to fully develop around the actors. But once they did, that freed the show to do what it had always done well: unfold a sitcom that understands that it exists in a post-sitcom era. (A favorite Max quote: “Wait, you’re breaking up with another boyfriend-of-the-week that I never get invested in except through dialogue?”) As Wayans tells me, “I thought that season one was kind of the bone structure of what the show was going to be, and this season we were adding muscles and tendons, and I think next season we’ll add some skin—you know what I mean—maybe a penis or a vagina. Boobs.”

And as the characters began to fill the shoes (or curves) of the actors who played them, the ensemble chemistry also began to take shape in a way that few could have anticipated. Pally and Wilson had been pals since their days at New York’s Upright Citizens Brigade—“We came in as freshmen together, and I was very interested in dating her, but immediately she got snatched up by the older dudes,” he says—but the rest of the group began bonding the night of the very first table read, when they went for drinks at the Chateau Marmont and ended up at Cuthbert’s house, where it became clear that this group of “friends” was actually going to be friends. “I hope he forgives me for saying this, but, I mean, Zach wore a fedora the first night we hung out, and it was just over,” Wilson says, laughing. “Adam and I were like, ‘Take the fedora off or we can’t move forward.’ It’s just like that—a questionable amount of openness.” Soon, the cast was going to Bikram yoga and getting margaritas after filming and encouraging Cuthbert to get a hot tub they could all hang out in and watching Happy Endings episodes at a now-defunct West Hollywood bar called the Silver Spoon. “I’d go around to everyone at the bar and very nicely go, ‘Do you mind if we watch this show? We’re on it,’ ” Wilson says. “And it’s always painful because the people in the bar are like, ‘We don’t watch the show.’ So we’re, like, watching them not watch the show.”

Even after filming together for fourteen hours, they’ll “tailgate” outside their trailers. “Guest stars hate it, because no one’s interested in talking to them,” Pally says. “We just want to know how everyone’s weekend was. Most of the time, we’ve spent it together. It’s disgusting.” In fact, there’s such a level of chumminess that the cast’s offscreen stories sound eerily like plots for a future episode, like the time Pally, Wayans, and Knighton got invited to the Playboy Mansion. “Those parties are just kind of crazy, you know what I mean?” says Pally. “Like, obviously, they’re exactly what you think of. Chris Evans was there, and he recognized Zach, and he was like, ‘Dude I love you, you’re a great actor, but that show you’re on is bullshit.’ I don’t even think he was talking about Happy Endings, I think he was talking about FlashForward, but I was a little under the influence, and so I got up in Chris Evans’s face like an idiot—because he would have destroyed me, he would have ripped my arms off—and I was like, ‘Whoa, not cool, Captain America.’ And then Damon backed me up, and I was like, ‘We’re going to kick the shit out of you, Chris Evans.’ And then security broke us up. So there you go.”

A third season is most likely on the horizon, viewership has doubled (reaching as high as 8.3 million), and the cast is remaining optimistic that the show will continue apace. Says Groff, “You kind of hope for the best and prepare yourself for the worst by laying in copious amounts of hard drugs.” And about that ill-fated party-bus trip: They turned that vibe around, too. “We decided to go see Bite, which is a lesbian vampire revue. That tagline alone was enough for me to just turn my credit card over and buy everyone a ticket,” says Wilson. “It was, like, off the strip, basically in an outdoor mall. It was just madness.”

Vulture on Set With Happy Endings, Part One

Cast members joke about raunchy pick up lines, having sex in bar bathrooms, and more.

Vulture on Set With Happy Endings, Part 2

Find out who’s the grabbiest of the group, and how the cast caps off a drunk night together.