Decades before he was the world’s buzziest dead novelist, Roberto Bolaño was a poet (he has the long-haired jacket-flap picture to prove it), and he maintained a crazy loyalty to the genre throughout his life. Even when he started writing fiction, it was almost always about poets writing poetry, reciting poetry, chasing lost poets, or spouting theories about poetry. (You might even say, maybe if you’re standing at the bus stop and no one else is around, that Bolaño didn’t so much write fiction as he did explore the novelistic aspects of poetry.) As a character in 2666 puts it: “only poetry isn’t shit.”

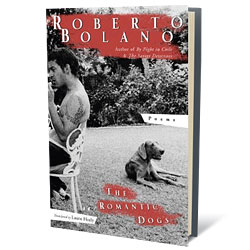

Now the translation boom has caught up with Bolaño the poet. This month, New Directions will publish The Romantic Dogs, a bilingual, career-spanning collection of Bolaño’s addictive poetry. In it, he rejects the civilized, intellectual verse of Paz and the previous generation and writes gritty, colloquial, rough-edged vignettes full of shocking imagery — as when he compares two painters, “One classic, eternal, the other / Modern always, / Like a pile of shit.” Readers familiar with his fiction will find many of the same virtues and subjects here, condensed: the obsession with detectives, with his friends walking the streets of Mexico City, with dreams and nightmares — and, of course, with poetry itself: “poetry is braver than anyone.”

If you want a Bolaño book that’s not going to tip your car over, or you need to know how to say menacing poetic things in Spanish (las tierras regadas con sangre me la pelan: “the soils watered with blood can suck my dick”), The Romantic Dogs will cover you on both counts.

Here’s one of our favorites — the story of a mother and her young son poignantly caught up in a mysterious apocalypse.

GODZILLA IN MEXICO

Listen carefully, my son: bombs were falling

over Mexico City

but no one even noticed.

The air carried poison through

the streets and open windows.

You’d just finished eating and were watching

cartoons on TV.

I was reading in the bedroom next door

when I realized we were going to die.

Despite the dizziness and nausea I dragged myself

to the kitchen and found you on the floor.

We hugged. You asked what was happening

and I didn’t tell you we were on death’s program

but instead that we were going on a journey,

one more, together, and that you shouldn’t be afraid.

When it left, death didn’t even

close our eyes.

What are we? you asked a week or year later,

ants, bees, wrong numbers

in the big rotten soup of chance?

We’re human beings, my son, almost birds,

public heroes and secrets.