Mitt Romney’s admission that he pays a low, low 15 percent rate on his income has occasioned a debate about why he pays such a low, low rate in the first place. Romney apparently benefits from the “carried interest” loophole, which allows private equity managers to enjoy their salary in the form of capital gains, which are taxed at less than half the rate of ordinary income. Almost everybody who does not work for the private equity industry agrees that this is unfair. What they don’t agree on is just where the unfairness lies.

The most common argument is that the carried interest loophole distorts the fine, upstanding purposes of the capital gains tax break. “The person entitled to the lower capital gains rate is the owner of the capital asset. But the US financial industry benefits from rules that allow non-owners the same benefit as owners,” complains David Frum. But the carried interest loophole actually demonstrates the folly of having a break for capital gains in the first place.

The general principle of taxation is that the government should be neutral as to how people earn their income unless there’s a super good reason why it should subsidize one way of earning money over another. The lower rate for capital gains is one such subsidy. If you invest your money in a Treasury bond or put it in the bank, your earnings are taxes at the regular income tax rate. If you invest it in stock instead, you get a much lower rate. Why should the government favor one form of investment over another? Proponents used to expound on the virtues of encouraging “risk taking,” though the financial crisis has made it a wee bit harder to claim that the government needs to subsidize higher levels of risk.

Frum argues now that the capital gains tax break makes sense because we’ve always had it — it’s “a policy that the US has followed almost from the inception of the income tax.” That’s not true. The capital gains break has ebbed and flowed over the years. The 1986 Tax Reform Act, signed by noted socialist Ronald Reagan, eliminated the capital gains tax break altogether. (It reopened in subsequent years as Republicans pushed hard to restore the subsidy.) The Bowles-Simpson plan would also have junked the capital gains tax break.

The carried interest loophole handily demonstrates the folly of taxing capital gains at a lower rate. The inherent problem arises when the government offers a better deal for one category of activity that isn’t easy to clearly define. Rick Santorum’s plan to eliminate corporate taxes on manufacturing is a perfect example — it would simply encourage every firm to try to legally define its activities as manufacturing. (If you doubt this, in 2004 Congress started handing out breaks for manufacturing, and it set off a wild wave of lobbying for various companies to claim the title. Film studios managed to categorize themselves as “manufacturers” of movies.)

The same holds true of capital gains. If “capital gains” are a special, lower category of income, then well-connected people will find ways to categorize their income as capital gains.

The capital gains tax break is at the heart of much of the sheltering in the tax code. It’s also the reason why very rich people pay lower tax rates than the middle class. Half of all the capital gains accrue to the richest one tenth of one percent. Some of those people — the most prominent being Warren Buffett — concede that it’s unfair that they enjoy a tax break that enables them to pay a lower tax rate than their underlings. But most enjoy the lower rates quite a bit and prevail upon Washington to keep things as they are.

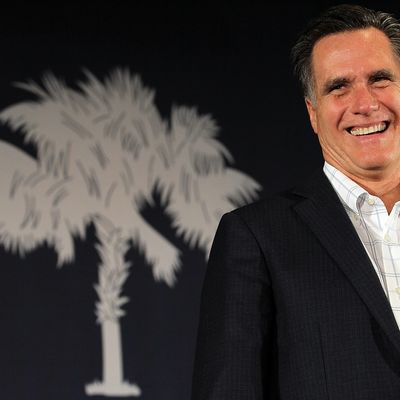

Obviously there’s nothing at all wrong with the fact that Romney took the lowest tax rates available to him under the law. But the issue does illustrate the nexus between his personal wealth and the policies he is promoting.

The capital gains break sits at the heart of the basic argument that has split the two parties for the last two decades. The Republican Party has been organized around the principle of minimizing tax levels on the rich, under every economic and fiscal circumstances, in every form and at every level of government. The Party is united around the principle of locking in the Bush tax cuts and deepening them for the rich, though candidates disagree on how much additional tax cuts the rich ought to enjoy. (Romney’s additional tax cuts for the rich are less generous than the staggeringly large ones on offer from most of his fellow candidates.) Voters may feel an instinctive distrust toward an extremely wealthy candidate who plans to preserve and deepen the advantages enjoyed by his own economic class, and they’re right to do so.