It’s easy to forget now, but when Mitt Romney first started running against Barack Obama, he imagined his primary line of attack would be foreign policy. This was 2009, remember. The economy was at its nadir, but most people underestimated the severity of the crisis and assumed the economy would be recovering by 2012. Obama was young, lacked much foreign policy experience, and seemed vulnerable to a nationalistic attack. Romney’s campaign book, written in 2009 and published in early 2010, was titled No Apology, using Obama’s imaginary habit of apologizing for the United States as a metaphor for his weakness and general un-Americanness.

Lots of things have happened since then. Last year we killed Osama bin Laden and the recovery stalled out, which made a foreign policy-based campaign appear wildly off point. But the recovery seems to be in earnest now, and the AIPAC conference has provided the backdrop for a series of Republican attacks on Obama’s handling of Iran:

Romney said Obama’s “policy of engagement” with Iran has given the country’s leaders time to further develop its nuclear program and the impression that the United States won’t stop the government from continuing it.

“This president not only dawdled in imposing crippling sanctions, he has opposed them,” he said. “Hope is not a foreign policy. The only thing respected by thugs and tyrants is our resolve, backed by our power and our readiness to use it.”

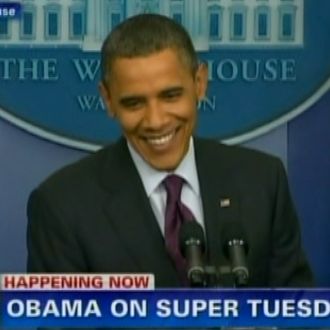

That is the political predicate for Obama’s press conference today, in which he pushed back against hawkish attacks from Romney. Foreign-policy debates generally favor the Republicans, which have a long identity as the more hawkish and nationalistic party. On the other hand, foreign-policy debates also tend to benefit the incumbent sitting president, as long as he’s not presiding over a perceived foreign-policy disaster. The two factors go hand-in-hand when a Republican incumbent is running — Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and George W. Bush (who, in 2004, was not yet widely seen to have committed enormous blunders in Afghanistan and Iraq) all used foreign policy to establish a stature gap over their rivals. They are the commander-in-chief, and this challenger lacks the experience and toughness to assume the mantle of governing.

Obama’s challenge is essentially to use his advantage as sitting president to bolster his standing to make the more dovish argument. His news conference offered the most crystallized version of what is likely to be his foreign-policy argument through the election. Obama repeatedly dismissed Republican attacks as bellicose political rhetoric. He argued that the demands he do more to stop Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon generally dissolve, upon inspection, into endorsements of policies he is implementing, like sanctions and using the threat of an attack as leverage. Obama tried to frame the critique as proof of his opponents’ lack of seriousness:

“Now, what’s said on the campaign trail — you know, those folks don’t have a lot of responsibilities. They’re not commander in chief,” Obama said.

“And when I see the casualness with which some of these folks talk about war, I’m reminded of the costs involved in war; I’m reminded of the decision that I have to make … This is not a game. And there’s nothing casual about it.”

Obama, probably without planning to, summarized his whole message when a reporter asked him to respond to Romney’s comparison of him to Jimmy Carter. “Good luck tonight,” he said, deflating Romney’s entire critique as so much political hot air. There is an element of professorial condescension at work here. His goal here is to disqualify his opponents, not by positioning himself as stronger, but by positioning himself as smarter.

Obama used a similar method in 2008 against John McCain, who tried to disqualify Obama’s fitness to conduct foreign policy. The difference is that the primary disagreement took place over Pakistan, an area where Obama staked out the more hawkish terrain, and McCain was the voice of caution. Now Obama is the president, and he’s using the same attitude, but harnessed to a more dovish argument. It probably helps that he’s the sitting president and his administration captured Osama bin Laden.