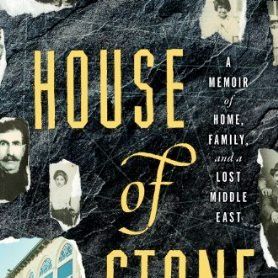

When people in the publishing industry say a book is “orphaned,” they mean its editor left before it was finished — quit Random House for HarperCollins, quit Penguin for Knopf, quit the book business altogether. It’s a handy term (not least because it happens all the time), but I wish it weren’t already taken, because it’s precisely the word we need to describe the stranger, rarer, sadder phenomenon suffered this month by Anthony Shadid’s House of Stone.

For anyone who somehow missed the story, Shadid, the Beirut bureau chief for the New York Times, died two weeks ago in Syria. One of the most acclaimed foreign correspondents of his generation, Shadid spent much of 2011 covering the uprisings of the Arab Spring; last month, he and a colleague, photographer Tyler Hicks, snuck into Syria to report on the ongoing violence there. A week later, while attempting to leave, Shadid suffered what seems to have been an asthma attack and died.

Shadid, 43, left behind a wife and 3-year-old son in Lebanon and a daughter from his first marriage in the United States. Also: a vast archive of stories, two Pulitzer Prizes, two previous books, and 50,000 finished, printed, not-yet-shipped copies of House of Stone. The book was originally scheduled for publication on March 27. Instead, it came out this week, which made it both early and late: a memoir transforming, at the last moment, into a memorial.

***

House of Stone is, itself, a book about orphaning, or at any rate about the permanent and devastating ways that the forces of history conspire to separate parents from children, sisters from brothers, lover from beloved. The titular house is located in the town of Jedeidet Marjayoun, in southeastern Lebanon, hard by the Syrian border and the Golan Heights. Shadid’s great-grandfather built it in the early 20th century; by the early 21st century, it was well on its way to ruin. In 2006, Shadid, then with the Washington Post, took a one-year leave from his job to rebuild it.

House of Stone, which chronicles that year, is a strange and often lovely hybrid — one-third memoir, one-third Middle Eastern history, one-third written version of what is more often an oral genre, popular among homeowners worldwide: the Contractor Nightmare Narrative. Shadid, who was born in Oklahoma City, arrives in Marjayoun with visions of restoring the home to Ottoman-era glory. In short order, he is disabused, not to mention just abused: by neighbors who are convinced he’s a spy, friends who second-guess his every architectural and financial decision, and, especially, by the workers themselves. Shadid’s carpenter is “so utterly lacking in punctuality that he measures time in seasons.” His painter turns out to be colorblind. His foreman, one Abu Jean, is 76 years old, prone to tantrums, sublimely indolent, staggeringly imperious, and somehow, despite all that, immensely likeable.

Just 800 people live in Marjayoun, which makes it one of those small towns where it is possible to be chronically lonely yet have virtually no privacy. Shadid gets by on scotch, cigarettes (enough “to keep the Carolinas out of the meth business”), and precisely the sense of humor one wants in a foreign correspondent: one part self-deprecating, two parts crude, four parts black, served very dry. It’s not right to call House of Stone a funny book; the humor here is too minor, in both senses — a secondary theme in a melancholy key. Yet Shadid is a very funny writer. A cousin’s elaborate exposition on curing olives feels like “a mix of nuclear engineering and Sufi mysticism.” His own efforts at bullying the construction crew into action are so ineffectual that a friend has to show him how it’s done. “You brother of a whore!” the friend shouts, “I fuck your sister!” He then pauses, considers, and recommends stopping there: “I wouldn’t want to bring mothers in at this stage.”

As Shadid struggles to make a literal and figurative home in this place, he recounts the story of why his ancestors left it. Separate, italicized sections detail the impact on Marjayoun of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, French imperialism, Lebanese independence, and the country’s fifteen-year civil war. Because many of Shadid’s relatives migrated to the United States, we also get a fragment of American history, slender and sharp. The first Shadids arrive when the Statue of Liberty still glows a bright, unoxidized copper and peddling remains a viable trade, “suitable for a country as yet unfamiliar with cars and buses and outlet malls.” Later generations get a green-tinged Lady Liberty and the auto factories of Detroit, “where they were known as Syrians or Turks.”

As House of Stone progresses, the family tree branches down toward Shadid; the main text and italicized sections gradually converge. Only late in the book did I realize that a subtle divergence was happening as well. As Shadid advances his own tale, the house gets ever closer to completion, until he moves in and makes a home. As he advances the historical sections, ancestor after ancestor deserts the house, until, finally, it slides toward abandonment and ruin. The effect is that of a film simultaneously projected forward and backward: the house falls apart and comes together at the same time.

It is, fittingly, a lovely structure. Or anyway, it’s a lovely structure for a book. But that endless cycle of rebuilding and undoing is also the structure of history, and seen too close-up, over too much time, it can sicken a reporter’s spirit. When House of Stone begins, Shadid has just spent three years covering Iraq. His wife — not coincidentally — has divorced him. He finds himself “stunned by war, and, shockingly, no longer young, or married, or with my daughter.” By the time he reaches Lebanon, he writes, “I was a suitcase and a laptop drifting on a conveyor belt.”

Has there even been a more concise description of the foreign correspondent at low ebb? The constant travel, the enforced passivity, the grim cyclicality, and above all the dissociation, the sheer thing-ness: on bad days, that’s how war reporters feel about themselves, the job, the region — the whole sweep of history.

Shadid comes to Marjayoun to escape all this, which makes House of Stone unusual among books by journalists. Rather than the culmination of a period of reporting, it is both a respite from the job and, indirectly, an account of the toll that job takes. Part of the book reads like an open letter of love and remorse to his daughter, Laila. “I wanted to be a family man, a generous man,” Shadid writes, “but there was always work.” In reality, the family man was “a kind of guest star, and sometimes, as wars accelerated, I forgot the plot unfurling back there.” He restores the Marjayoun house in part because he cannot rebuild his other neglected home.

And there is another lost home here, too. House of Stone is, among other things, a torch song for the Levant, that swath of the Mediterranean that is partly geopolitical reality and partly “a way of living and thinking”: an idea of the Middle East as “open-minded [and] cosmopolitan.” That Middle East, Shadid observes, has now all but vanished, “transformed into a puzzle of political divisions,” engulfed by chronic war.

Shadid is openly tired of “the dread of yet another conflict,” and in Marjayoun, for the most part, he avoids it. Instead he tends his garden — literally — and wonders when to harvest his olives; the men around him die of cancer and old age. In both tone and content, the book is hushed and meditative, a few adagio measures in the middle of a prestissimo life. Yet the threat of war is always there in the background, “a television turned low.” Even without the book’s backstory — which, at present, feels more like a front story — it would be impossible to shake the sense of foreboding.

I suppose that’s because the endeavor at the heart of House of Stone seems so tragically doomed. Shadid makes hay of the surface craziness of his home-improvement project — the Keystone Cops construction crew, et al. The real craziness, though, is both bigger and simpler than that: the idea that by rebuilding a house, Shadid can somehow restore to wholeness himself, his family, and his homeland.

That is the ethos familiar to us all from the tale of the three little pigs: Build your house with love and care and strong materials, and nothing can blow it down. But Shadid plainly knows better. In the opening scene of House of Stone, southern Lebanon has just been bombed, and Shadid sets off to assess the damage in Marjayoun. At his great-grandfather’s house — the one he will later determine to rebuild — he finds “a half-exploded Israeli rocket that had crashed into the second story … taking out a good chunk of wall before bursting into flame.”

Rebuilding and undoing, rebuilding and undoing. Shadid, of all people, knows exactly how fragile a home really is. Yet he goes to a neighbor, borrows a shovel, and plants, in the friable soil and the shadow of a rocket, an olive tree. One year and 300 pages later, it has barely grown; but the house, miraculously, is near completion. And how does Shadid feel about that? “I can already sense it,’” he tells a friend. “I’m going to finish this house and the war will start. I’m going to finish this house and I’ll end up never setting foot in it again.”

***

When David Foster Wallace committed suicide in 2008, he left behind the unfinished manuscript that would become his final, posthumous work, The Pale King. Perhaps the novel’s most disconcerting feature is that, at regular intervals, a character named David Wallace pops up to address the reader, announcing each interruption by saying, “Author here.”

This is the thing about orphaned books, if I may appropriate the term. They constantly announce the impossible: Author here. The voice on the page persists, innocent of what is about to happen, or rather, what has happened already. As W.H. Auden wrote in his elegy for Yeats, “the death of the poet / was kept from his poems.”

Anthony Shadid knew his job could kill him, because it almost did, twice. In 2002, he was shot by a sniper in Ramallah; last year, he and three other journalists were captured and beaten in Libya. Yet only in the epilogue to House of Stone, when he is covering the Arab Spring — and, by all accounts, happy to be back at work — does he talk about the emotional experience of confronting death: of lying with his face in the dirt while above him, a Libyan soldier calmly says, “Shoot them.” What he experienced in that moment was nothing you or I might recognize as mortal terror: “It was emptiness, aridity, hopelessness, the antithesis of creation.”

That sounds almost too writerly to be true, but listen to Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuscinski, another best-correspondent-of-his-generation: “I have only ever felt true loneliness … when I have stood alone face-to-face with absolute violent power,” Kapuscinski wrote in Travels with Herodotus. “The world grows empty, silent, depopulated, and finally recedes.” Silence, emptiness, aridity, the antithesis of creation. Death, to both journalists, felt like the end of being able to say something: Author not here.

I suppose it is banal to point out that all authors cease to be here sooner or later. Yet that is precisely the thing about death: it is banal, just as it is (at least in broad outline) entirely predictable. Only when it explodes into the stone wall of your own home does it become astonishing and terrible. Shadid spent his life trying to bridge that gap; his work insists on the non-banality of other people’s experiences. As House of Stone makes clear, that kind of work takes a remarkable person, a remarkable toll, and a remarkable, impossible faith. As awful as his death is, it comes with a kind of informed consent. Rebuilding and undoing: over and over, Shadid cast his lot with the former, fully knowing the risks and tradeoffs, fully knowing that — straw, sticks, stones, bones — we are all blown away, eventually.