On any given summer Sunday, Governors Island has the feel of an urban day camp—seasonal, boisterous, and irresistibly ramshackle. Every weekend, thousands of people—nearly 450,000 in all last year—stream off the ferries from Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens and fan out through the ex-military ghost town. Some rent a bike, circumambulate the island, and go home. Others spend the day and picnic, watch glassblowing demonstrations, climb on sculptures, stand on line for jerk chicken, stretch out on hammocks, play mini-golf, explore the old fort of Castle Williams, and gaze at the disorienting marvel of the harbor views. And all the while, those leisurely crowds have been unwittingly deciding the future of Governors Island.

After a decade-plus as a blank slate on which futurists and fantasists have projected oversize desires—a new Globe Theatre! A SpongeBob SquarePants hotel! A gondola to Manhattan! An offshore campus for NYU! Another Trumpville!—the backhoes have finally gotten down to business. With $260 million of the city’s money, workers are shoring up seawalls, running pipes and cable, reroofing historic buildings, and, most dramatically, shaping a new landscape. While bureaucrats wrangled and budgets festered, the Dutch architect Adriaan Geuze and his firm West 8 spent years observing the summertime crowds and their habits of leisure. They have plowed that knowledge into a design that’s ambitious and spectacular, but also freewheeling and improvisational.

When the first and largest section of the new park opens in October of next year, the island will rejoin the city that was born there. The first Dutch arrivals camped on the wooded isle they called Noten Eiland (Nut Island), but one form or another of the military has monopolized it ever since. When the Coast Guard finally moved out in 1996, leaving a collection of gracious nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century brick structures, some slablike barracks, and an abandoned Burger King, it also left behind 172 acres that New Yorkers barely knew existed. In the ensuing years, a growing stream of visitors has come to love the island’s pleasantly derelict air, reminiscent of a spa resort past its prime or a boomtown after the silver has dried up. Here, shabbiness is a resource.

Leslie Koch, president of the Trust for Governors Island, was canny enough to realize that one thing her little kingdom didn’t need was an oppressively chic garden with look-but-don’t-touch plantings and gold-plated views. Instead, she demanded a rare and precious thing: a space designed for the way people actually behave rather than the way architects think they ought to. Circling the island on bicycles, she and her staff are constantly watching. They see large families arrange picnic tables end to end, before spinning apart and sorting by age. Young children pile into a hammock, commandeering it as a group swing. Older kids bike freely on the carless paths, or flip Frisbees across the parade ground. Adults circle the Adirondack chairs for conversation or nap on lawns unsullied by dogs (which are banned from the island).

These observations shaped dozens of design decisions. The future Governors Island will be dotted with tables and recliners solid enough to withstand the crowds and the scouring, sea-salted air but light enough to move around. An experiment in which a few movable hammocks were sprinkled around an open area evolved into Hammock Grove, which will look like a cross between an orchard and a shipboard berth deck. The play area will include a hammocklike mesh swing ample enough for half a dozen kids.

Most architects think visually. Good architects tend to all the senses. Even in the plans you can practically smell the saltwater and the echinacea beds, listen to the soft marine soundtrack of a postindustrial harbor, and experience the varied textures underfoot of greenswards, granite mosaic, asphalt paths, and gravel beds. This is a park designed not just by computer, but by feel. The curvature of pathways and height of signs was calculated to keep bikers moving—slowly. Benches were given the butt test. Even the decision to create gathering spots for food trucks and stands, rather than build a permanent (and permanently mediocre) cafeteria is ultimately a sensual choice.

West 8 packs a lot into 30 acres. Cutting through the center is a varied topography of amusement. Manicured flower beds segue into miniature woodlands and sudden panoramas. A later phase, provided it gets funded, will refurbish the two-mile promenade that encircles the island and add a cresting wave of earth called the Hills. I hope this bit of virtuoso terraforming eventually happens, but even without it, the new Governors Island will be stunning place, a maritime park unlike any other in the city, crouched low to the water yet close to the open sky.

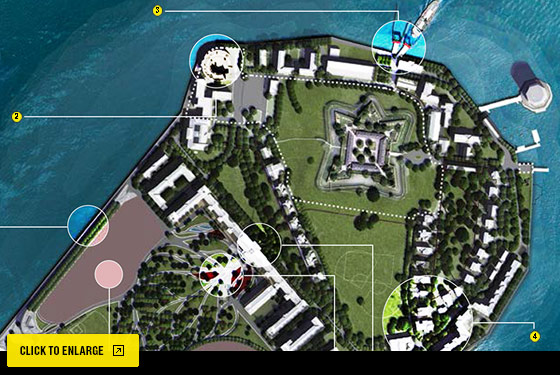

Disembarking after the seven-minute ferry ride from Manhattan, you’ll arrive at an area conceived for that moment of confusion when you’re not even sure what you’re looking for. A see-through metal portal announces that you’re at Soissons Landing and directs you toward an attractive-sounding menu of locations: Hammock Grove, Picnic Point, Play Lawn. The design has its share of grandeur but also a sense of play that saves it from preciousness. The long brick belt of Liggett Hall, a severe Georgian revival barracks designed by McKim, Mead & White in 1929, cinches the island’s middle. Behind the building was a flat, forbidding expanse of asphalt and patchy lawn. In 2008, an arts group installed a fanciful miniature-golf course there, and the area came suddenly, if sporadically, alive. In the new design, the unbending symmetry of Liggett Hall and the star-shaped Fort Jay gives way to a zone of curving paths, geysering water jets, and petal-shaped perennial beds. Those curves are reproduced at every scale—in the squiggly lines carved into the undulating surfaces of precast-concrete benches and in the bending borders of the park. Toddlers can get thrillingly lost and still be supervised in the sinuous mazes, their boxleaf-holly walls shin-high to an adult. The layout is asymmetrical but rational, complex yet intuitive, echoing nature’s fractal patterns without being ostentatiously avant-garde. Military protocol has been vanquished by flower power.

The new park won’t complete the story of Governors Island. The plan leaves over 33 grayed-out acres of “development zones,” which will one day pay the bills for all that public space by sprouting theme parks, schools, conference centers, or whatever entities can thrive in an island habitat. The blanks seem ominous for now: There are so many ways to ruin this magical place. (Not with apartment buildings and casinos, though; the deed forbids both.) But Geuze has done what he could to protect against future monstrosities: He has enshrined the island’s sensibility in a deliciously mellow design.

Governors Island Park & Public Space

Adriaan Geuze and West 8 Architects. Opening Fall 2013.

Click to see the full map.