The imminent Americanization of the Libor-rigging scandal, an imbroglio that has already forced the resignation of one major bank CEO and forced many others to quake in their wingtips, is as good an occasion as any to revisit the flawed rate at the heart of the scandal, and figure out if it’s beyond repair.

For those who haven’t been keeping up: Libor, which stands for the London Interbank Offered Rate, is a benchmark interest rate that is used for a whole bunch of swaps, adjustable-rate mortgages, municipal bonds, and other important-but-boring financial instruments. If you have ever borrowed money — for a house, a car, a masters degree in interior design, or a trip to Tahiti — your interest rates may have been pegged to it. In all, about $360 trillion worth of stuff depends on Libor, which makes it prettay, prettay important.

You might think that such a crucial interest rate would be quadruple-checked and fail-safe, impossible to tamper with and impervious to attack. But Libor, as everyone now knows, is run on the Wall Street equivalent of the honor system. Bankers and traders could (and did) lobby their bank’s Libor submitters to send in false rates, knowing it would make their trades more profitable or their bank’s balance sheet look healthier.

Here’s a very dumbed-down version of how Libor submission works: The dozen or so banks who set Libor each designate one guy — let’s call him Joe — to tell the British Bankers Association, via Thomson Reuters, roughly how much it would cost his bank to borrow money from other banks. Every morning, Joe asks around the office and submits his bank’s estimated cost of borrowing, which is then combined with the numbers from other banks. A few outlier numbers are thrown out, and the rest are averaged to come up with an inter-bank lending rate. Voilà, Libor.

Now, obviously, Joe can be less than honest in submitting his bank’s numbers to London, or else we wouldn’t have gotten the Li-Bros, “Done for you big boy,” or any of the other fallout from the revelation that that the Libor-setting process at many banks, as of several years ago, consisted of submitters pulling numbers out of what, in the Queen’s English, are called their “arses.”

Bloomberg View’s one-sentence summation of why Libor is problematic is pretty clear: “Instead of gleaning information from actual transactions, Libor relies on banks to report their borrowing costs honestly, something they spectacularly failed to do.”

So, okay, Libor sucks, and Joe can’t be trusted. But the most interesting question to have emerged from Liborgate thus far is: What should replace it? Is it possible to build a better benchmark interest rate?

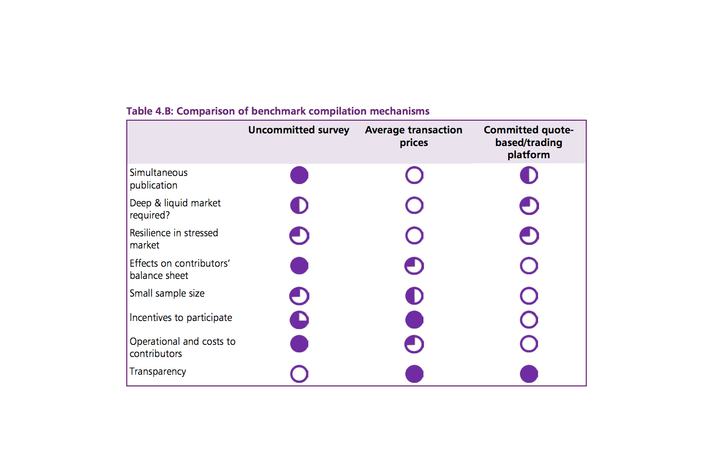

I finally got around to reading Martin Wheatley’s report [PDF] on what’s wrong with Libor, and how to fix or replace it. Wheatley, the managing director of the UK’s Financial Services Authority, came up with a pros and cons list of possible Libor alternatives that, in accordance with some British data visualization convention I’ll never understand, he put in a chart that consists of lots of little pie charts:

Let’s translate that chart, which is actually pretty important to understanding the debate about replacing Libor, into American.

What Wheatley is saying is that there are three possible ways to come up with a benchmark interest rate. As we currently do with Libor, you can ask banks what interest rate they would pay for some imaginary transaction, then compile all the different responses and take an average. (Wheatley calls this the “uncommitted survey” solution.) Or you can make banks report the “average transaction prices” they paid for some set of actual trades. Fed chairman Ben Bernanke is a fan of this kind of market-based solution, since it relies on actual data rather than just asking Joe to take a quick office poll.

Alternately, you can have banks partake in what Wheatley calls a “committed quote-based/trading platform,” which is a very fancy way of saying that regulators would set up a system in which each bank would have to submit a price at which they’d be willing to do a certain trade, then actually execute that trade if another bank liked the quote. This would make it harder for banks to cheat, Wheatley writes, because it would force banks “to only submit quotes that they are willing to honour.” (Honour! So very British!)

As Wheatley’s pie-chart-chart shows, each of these methods has benefits and drawbacks, but “uncommitted surveys” — the kind of process used to set Libor — is probably still the preferable option.

Uncommitted surveys, as we’ve learned from Liborgate, are obviously problematic because they often allow for deception. Rates based on average transaction prices would be good because they’re pegged to actual market data, but the rates banks pay for these types of short-term trades would be subject to wild swings in times of financial panic. The third solution, a quote-based trading platform, would be totally transparent, but also prone to manipulation, seeing as the entire thing would basically amount to a game of Wall Street chicken (“How wide do I have to make my bid-offer spread so that no bank takes me up on it?”).

And with any Libor replacement, you’d have to tear up every single financial contract pegged to Libor — all $360 trillion of those swaps and mortgages and Tahiti trip loans — and rewrite them with a new, mutually agreed-upon rate. That would be really hard.

Wheatley’s conclusion, which I mostly agree with, is that if our goal is a daily, wide-ranging snapshot of the interbank lending market, a rate based on an uncommitted survey (in other words, Libor — or something very much like it) may be the best option we’ve got, despite its obvious flaws. And strengthening sanctions against banks who fail to report honest numbers may be a superior option to forcing the entire financial system to use a new, untested type of benchmark rate.

The best way to build an hard-to-hack Libor, in other words, may be reforming the process to make it harder and more dangerous to cheat, rather than replacing it entirely.

That’s not a very satisfying answer for those Main Streeters who have been burned by faulty Libor submissions, or for those who believe — quite reasonably — that Wall Street has proven itself incapable of working on any self-submission system. Gary Gensler, the head of the CFTC and one of the U.S.’s top regulators, is one of the many authorities who have made compelling calls for strong Libor reform.

“This is the mother of all benchmarks and markets work best when they’re transactions-based, when they’re fact-based, rather than — excuse the expression — fiction-based,” Gensler recently told a Politico gathering.

But even Gensler, who has been as vocal as anyone on the flaws in the Libor-setting process, admitted that regulators can’t exactly force Wall Street to stop using the rate, no matter how corrupted it is.

“Ultimately it’s gonna be the markets — the borrowers and lenders and derivatives users that might move to something else,” he said.

So, sure, let’s subpoena every Libor-submitting bank and prosecute the hell out of the traders who conspired to rig Libor. Let’s recover as much money as possible for municipalities and other borrowers who were the victims of the rigging, and let’s severely increase penalties to deter future riggers.

But let’s not forget in our anger that there are some benefits to calculating a benchmark rate the way we currently calculate Libor, and that the alternatives might not be any safer or more accurate.

If Gensler and other top regulators are publicly expressing doubts that a government-implemented Libor alternative would work, it’s probably time for pragmatists to start asking how the world’s most important interest rate could be improved, not whether it’s worth keeping at all.