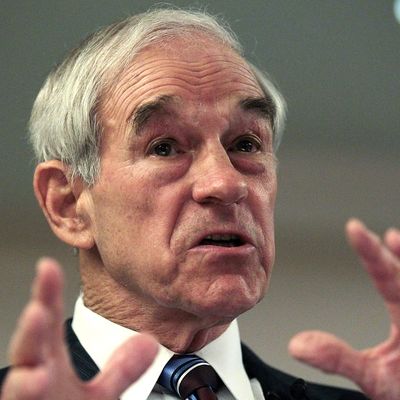

So on Thursday morning, Beth Reinhard, a reporter for National Journal, is having a go at the breakfast buffet at the Embassy Suites in downtown Des Moines — when Ron Paul ambles in, piles his own plate high with grub, and begins to chow down. As Reinhard tells it, she approaches the Iowa co-front-runner and asks if he is at all concerned about the possibility that, if he doesn’t win the Republican presidential nomination, his supporters might refuse to rally around the person who does. “Right now,” Paul grouses, “the only thing that bothers me is people who don’t respect my privacy enough to leave me alone for five minutes when I’m eating breakfast.”

Reinhard’s reaction to Paul’s snappishness is a single word: “Charming.” I confess to having the same reaction, minus any trace of sarcasm — and I suspect that more than a few voters, on hearing the story, would feel the same way. Paul’s crankiness is, if nothing else, entirely genuine, a reflection of authenticity. It is not a problem; it’s a big part of his appeal. What is a problem, however, is that Paul is more than merely cranky. He also happens to be a crank: a genuine, authentic crank, in the strictest sense of the term. And the fact that a crank may win the Iowa caucuses — and in so doing potentially scramble the GOP race more, and more unpredictably, than most people assume — is arguably the most compelling story going on in politics right now.

This notion of Paul as a certifiable crank was rattling around my head when I trailed him for a full day earlier this week. Observing Paul in action, I couldn’t help recalling a brilliant New Yorker piece from 1996 by the late, great Michael Kelly. The story was about that year’s presidential running mates, Al Gore and Jack Kemp, and was titled “Cranks for Veep.” Kelly allowed that Gore and Kemp weren’t “full-bore crackpots — not Baconians or orgone-box men or numerologists — but [they are] definitely cranks, and of a definite sort. They are examples of what you could call the Esperanto-type crank … a sort of unified-field theorist, a believer in the one great idea that will fix everything.” Kemp, wrote Kelly, was a “glory-of-capitalism man: he believes that if the big money machine can ever be built just right, and oiled just so, it will drive the world forever in humming happiness.” For Gore, on the other hand, “the one great idea is systemology— that everything is connected to everything else, holistically, and that fixing it all is just a matter of getting all the systems running right.” And though both men were surely professional politicians, both were motivated by a calling more earnest and exalted than moving votes; for them, “any audience [was] one chance more to move one step closer to universal understanding.”

That Paul is another Esperanto-type crank is evident in all of his appearances, at which he lays out his own unified-field theory — libertarianism, simply put, though in fact what that means is a combination of radical free-marketeerism in the areas of fiscal and monetary policy and radical original-intent constitutionalism with regard to foreign and domestic policy — with great consistency if not the optimal degree of coherence.

In the cafeteria of GuideOne insurance in West Des Moines, for example, I listened as Paul opened up his talk with ten solid minutes on the glories of Austrian economics; railed against the evils of paper money; suggested he would withdraw U.S. troops from South Korea and Germany; skittered over to the budget, pledging to cut $1 trillion in his first year as president; pivoted to the dangers of regulation (in pretty much any instance); warned that the government was trying to “take over the Internet” in order to spy on its citizens; decried the coming accrual of “dictatorial-type powers” in Washington; and contended that America faced no dangers from abroad, declaring flatly, “Nobody is going to invade us! Nobody is going to bomb us!”

As Paul rattled on, I closed my eyes and pretended that I wasn’t at a presidential campaign event. The image that immediately filled my mind was that of an addled, geriatric berzerker with bushels of hair growing out of his ears, sitting on a park bench, talking to the trees and the phantoms in his head, feeding stale bread to the squirrels. When I opened my eyes and looked around at the GuideOne employees in the cafeteria — who must have been promised that they could go home early if they were willing to endure Paul’s gibberings — they wore sad, defeated, dazed expressions, as if they’d been bludgeoned with broomsticks.

The Paulistas, of course, don’t look anything like that: They are ecstatic, exultant, riled, and razzed up to the rafters. In a presidential cycle that has featured notably small and docile crowds at the events of the Republican contenders, Paul’s have been the sole and dramatic exception. Later that same night, at least a thousand of his supporters — many of them festooned in “Don’t Tread on Me” paraphernalia —filled a hall at the Iowa State Fairgrounds, hooting and hollering and delivering the candidate a rousing series of standing Os.

What accounts for the intensity of Paul’s support, not to mention the fact that it has swelled to a little over 20 percent of the Iowa electorate, according to every credible recent poll? Two things, I think. On one hand, you have a series of policy positions that, stripped of his loopy rhetoric, appeal mightily to left-libertarians (especially the college-age variety), from his opposition to “endless wars” to his support for legalizing drugs. On the other, you have a strain of paranoia that appeals to the most zealous quadrants of the anti-government right, up to and including the clenched-fist-and-camouflage crowd. In every speech he gives, Paul talks about taking an oath to protect the country from “enemies foreign and domestic” — he practically hisses that last word — and then moves directly to condemning the Patriot Act, not merely as an ill-conceived piece of legislation but as a dark plot waged by our government to strip the American people of their rights and liberties.

Paul’s practice of what Richard Hofstadter famously called “the paranoid style of American politics” is not new; he has been at it for years. In an unsettling blog post at NYTimes.com, the New Republic’s James Kirchick details Paul’s support for the militia movement and other fringe groups — including the John Birch Society, whose 50th anniversary gala dinner he keynoted in 2008! — and flirtation with a range of conspiracy theories, from those implicating the Trilateral Commission, the Council on Foreign Relations, and the Rockefeller family as part of a globalist cabal to the idiocies of the 9/11 “truthers.”

The last significant presidential candidate to deploy this brand of paranoiac politics was Pat Buchanan. And that’s a precedent worth considering. The conventional wisdom about Paul this year is that he has a high floor (owing to the passion of his adherents) but also a low ceiling (owing to the large number of positions he holds that are far outside the Republican mainstream). According to a new NBC News/Marist poll released today, fully 41 percent of likely Iowa caucusgoers regard him as “not acceptable as the Republican nominee” — nearly double the number who say the same thing about Mitt Romney. It is all but impossible to find any serious political person in Iowa who believes that Paul could secure more than 25 percent of the vote here next Tuesday, just as trying to locate any sensible Republican who believes that he can win the Republican nomination would be a fruitless endeavor.

But as Buchanan proved in 1996, the fact that a candidate is incapable of being the GOP standard-bearer doesn’t mean he can’t kick up a hell of a ruckus along the way — and pose significant problems to the Establishment choice for the nomination. Buchanan, please recall, finished second in Iowa to Bob Dole with 23 percent of the vote that year, then went on to beat the front-runner in New Hampshire. It is true, to be sure, that Romney is a stronger Granite State candidate than the Bobster was, and if he wins in Iowa, the Paul threat will quickly recede. But if Romney were to slip to third behind Paul and Santorum, the situation in New Hampshire might fast become unstable — and in South Carolina, even more so, as Romney would be forced to contend, in a state where he has never been strong, not just with Paul and Santorum but with Rick Perry and Newt Gingrich making what might be their last stands.

And then there is another scenario: one in which Romney wins the nomination, but Paul refuses to disappear. The other day, one of the savviest political operatives I know e-mailed me out of the blue. The subject line of the message read “Romney’s mistake” and its body said this: “He thinks that he is running against Paul for the nomination. What he needs to start focusing on is how to get Paul to not run as a 3rd party candidate in the fall” — an eventuality that could cripple Romney’s chances in the general election by robbing him of crucial conservative-libertarian votes. I e-mailed back: What would you suggest? “Stay away from him,” came the reply. “Don’t engage him and don’t insult him. Maybe even find something to agree with. They are not competing for the same voters.”

Romney has not followed that advice, however. Although, unlike Gingrich, the former Massachusetts governor has affirmed that he would vote for Paul if Paul were the nominee, he has also criticized Paul regularly in the runup to the caucuses. Paul, for his part, has said little in response, though his campaign ads on the Iowa airwaves have assailed Romney as a “flip-flopper.” More to the point, Paul has consistently refused to rule out a third-party run should he fail to win the nomination. In fact, in his talk at GuideOne, Paul argued that both Occupy Wall Street and the tea party were expressions of frustration with the traditional political structure: “A lot of people are not so happy with the two-party system,” he noted. And then he went on to say that there isn’t a dime’s worth of difference between Democrats and Republicans on the issues that matter most, from foreign and monetary policy to the debt and deficit.

Maybe Paul was just being cranky. Certainly, he was being a crank — it is what he is. But either way, no matter what happens in Iowa, I suspect we won’t have heard the last of him. And Mitt Romney won’t have, either.

Related: Third-Party Candidates Line Up