The political press corps has decided that the “moment” of Saturday night’s Republican presidential debate occurred when Mitt Romney decided to challenge Rick Perry to a $10,000 bet. In the most direct sense, it is a false controversy. Wealthy though Romney may be, as a committed Mormon who can’t gamble and an equally committed tightwad, he’s the last guy who’s going to run around throwing down high-stakes bets on a whim.

I do think the debate exposed a deeper problem for Romney and the Republican Party. Romney is obviously conscious of his wealth and determined to avoid the stereotype of an out-of-touch rich guy interested only in protecting his own. And yet the party is committed to a policy agenda that involves enriching people in Romney’s tax bracket. This combination renders him an especially poor vehicle for the GOP agenda.

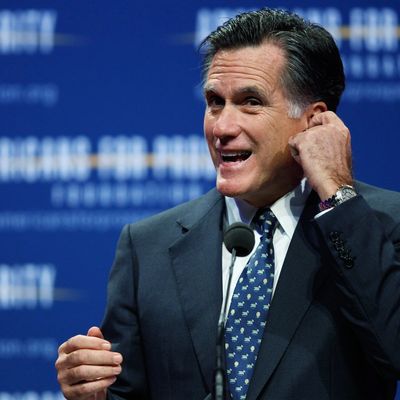

All the presidential candidates, including President Obama, are rich by the standards of the average American. But Romney is especially rich, and not just numerically. He looks and sounds like a paragon of the upper class, with his regal appearance, precise diction, and dignified graying sideburns. This has forced him to defensively cast himself as a middle-class champion, foreswearing at every turn any interest in benefiting the rich.

The most dramatic example concerns his proposal on capital gains. Reducing the tax rate on capital gains is the centerpiece of the Republican domestic agenda. Capital gains represent a huge share of income for the very rich, and the lower rate for capital gains income (as opposed to salary income) largely accounts for the fact that Warren Buffett pays a lower tax rate than his secretary. George W. Bush cut the capital gains tax, and most leading Republicans want to eliminate it altogether.

Romney proposes only to eliminate capital gains taxes on income under $200,000 a year. That would cover just a tiny portion of capital gains, making it essentially a symbolic measure. A few months ago, The Wall Street Journal editorial page railed against Romney’s plan. The problem, the editorial noted, was not just that Romney wasn’t offering any new tax breaks for the rich. It was that the retreat “suggests that he’s afraid of Mr. Obama’s class warfare rhetoric” – that, in general, he will shrink from the task of advocating for policies that increase income inequality.

Any conservatives liable to worry about this would be positively alarmed after hearing Romney defend his position on Saturday night. During one portion of the debate, Romney mentioned that he, unlike Newt Gingrich, would restrict his capital gains tax cut to those under the $200,000 annual threshold. Gingrich replied, accurately, that households under that ceiling have barely any capital gains. Romney replied:

And — and in my view, the place that we could spend our precious tax dollars for a tax cut is on the middle class, that’s been most hurt by the Obama economy. That’s where I wanna eliminate taxes on interest dividends and capital gains.

“Spend our precious tax dollars” — that is a phrase to strike terror in right-wing hearts. For twenty years, the basis for Republican budgeting has been to refuse to acknowledge any tradeoff between cutting taxes for the rich and other governmental priorities. The Democratic position is to insist that tax cuts for the rich be measured against other possible choices — lower taxes for the rich mean higher taxes for the middle class, or lower social spending, or higher deficits. Here, Romney is actually employing the Democratic formulation.

Indeed, he is doing it in the way most prone to enraging conservatives — by describing the choice to cut taxes as a form of spending — a formulation that for several decades has prompted the conservative auto-response that this phrasing presumes all taxpayer dollars belong to the government.

Every additional episode that highlights Romney’s wealth merely increases the pressure he surely feels to avoid the vulnerabilities associated with championing the rich. Republicans have usually sought to avoid this problem by nominating candidates who can at least sell themselves as authentic representatives of the middle class. George W. Bush may have been handed enormous wealth by his patrician family, but he crafted an image of himself as a kind of Texas dirt farmer, with his modest “ranch” serving as the background. Nominating Romney, stripped of any such cover, raises the risk for Republicans that he may be a pacifist in the class war.