Thinking is hard. Thinking about fiscal policy, one of the most boring subjects on earth, is even harder. So it’s natural that most normal people don’t know much — or care — about the sequester, the latest manufactured political crisis threatening the future of the country.

But the sequester fight is incredibly crucial to the domestic economy and the future of government-run programs. And more importantly, unless you learn what’s going on, you’ll feel stupid at your dinner parties this week, when everyone is talking about it and you’re making eyes at your salad fork.

So we’re here to help. In much the same manner as we brought you up to speed on the European debt crisis, the fiscal cliff, and QE3, here is our Absolute Moron’s Guide to the Sequester.

Hello again! I hear we’re talking about QuestLove today? Why are you bringing Jimmy Fallon’s drummer into this?

No, we’re talking about the sequester.

Sequester? I don’t even kno—

Stop that right now. The sequester is no laughing matter. It’s an old term that has been used in budget politics since the Reagan administration. And these days, it’s shorthand for an imminent political crisis that could do lasting damage to many of our most cherished national programs beginning later this week.

Oh. So, this has nothing to do with Jimmy Fallon.

I’m afraid not. Anyway, do you have any idea what is slated to happen this Friday?

Well, I get my paycheck, so I am going steeeee-raight to the mall to get myself some new One Direction t-shirts. But I feel like that’s probably not what you’re going for.

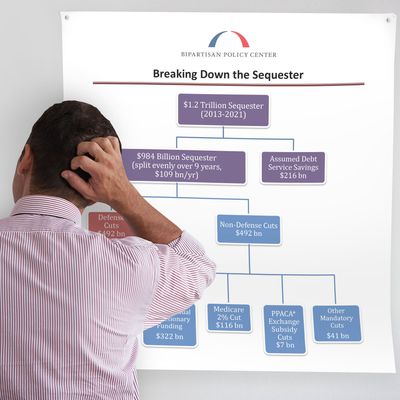

Correct. The bigger thing is that it’s March 1, and a bunch of federal spending cuts are scheduled to kick in automatically. These cuts are called the sequester. They will swiftly and dramatically reduce the amount of money available to the military, the FBI, the SEC, and a host of other agencies and programs with three-letter acronyms, in a big chunk that will total $85 billion by the end of the year.

But that’s a good thing, right? After all, less money for those guys is more One Direction merch for me!

It doesn’t really work like that. In fact, the money wouldn’t go anywhere else — it would simply vanish from the budget. But the automatic spending cuts would create real and lasting damage to a lot of things you probably care about: national parks, hurricane relief programs, local school districts, food-safety inspection, unemployment benefits, the zoo.

Hold the phone. THE ZOO is going to be affected?

Yes. The Washington Post says that the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., may have to scale back plans for a “planned acquisition of cheetahs” if its funding is cut.

I thought D.C. was already full of cheaters. And why are you doing a Boston accent?

I said “cheetahs.” They’re a type of large cat.

Oh. So, why do these automatic spending cuts exist, again?

It’s a long story, but it goes back to 2011, when politicians were arguing about how to deal with the debt ceiling and pare down the federal deficit. The Supercommittee was supposed to come to a deal —

Wait, there was a thing called “the Supercommittee”?

Yes.

So awesome! If I had a superpower, it would be eating Chipotle burritos without getting tinfoil in my mouth.

That’s wonderful. Anyway, the Supercommittee was a bipartisan group of congressmen that was supposed to figure out a way to trim at least $1.5 trillion from the deficit over ten years – a way that would be acceptable to both Democrats (who liked the idea of raising taxes on the wealthy to pay for stuff) and Republicans (who liked the idea of cutting government programs so there’s less stuff to pay for). To motivate both sides to reach an agreement, a quirky rule was put in place: If they failed to compromise, a series of cuts to government spending would kick in immediately on January 1, 2013.

That was the fiscal cliff thing I vaguely remember, yes?

It was part of it. Anyway, the idea behind these automatic cuts was that they would be so severe, so unthinkably brutal, that they would never be allowed to happen. With the only alternative being the sequester, the thinking went, the Supercommittee wouldn’t be able to fail.

So what happened?

It failed anyway. And then the fiscal cliff deadline hit and the sequester kicked in — or would have kicked in, anyway, if Congress hadn’t extended the deadline by two months.

I still don’t get it.

Okay, so let’s use a different example: Imagine you have two tickets to the next One Direction concert, and you’re negotiating with your BFF John over who gets to sit closer to the stage. In order to motivate each other to reach a deal, you say, “Okay, John, if we don’t figure this out, we’ll tear up both tickets and go see my uncle’s crappy grunge band play in his garage instead.” And now, it’s the day of the show, and you and John still haven’t reached an agreement, and now you’re headed to your uncle’s house while Harry Styles is doing a soundcheck. Your uncle’s crappy grunge concert is the sequester.

Ah, I see. So, who’s worried about the sequester?

Basically everyone. Republicans hate it because it’s going to cut $42.7 billion from the military’s budget. Democrats hate it because it will shave money from the budgets of programs like Head Start and the National Institute of Health, put government employees out of work, cut unemployment benefits for the nation’s poor, and take an ax to all kinds of federal infrastructure and research projects. (The New York Times has a roundup of the various ways agencies are preparing themselves for sudden financial doom.) And everyone is worried that cutting $85 billion from the federal budget this year will hurt the national economy — by most estimates, the sequester would reduce GDP by around a half-percent this year and cause a significant spike in the unemployment rate.

That sounds bad. Is anyone not worried about it?

A few — namely, those who don’t think the military needs as much funding as it currently gets, and a few Republicans and libertarian think-tanks that are dead-set on cutting federal spending by any means necessary and think even a harmful sequester would be better than no deficit reduction at all.

So politicians are going to come together this week and solve this thing, right?

Well, that remains to be seen. Basically, Republicans in Congress are displaying intransigence —

Intransigence? That sounds like something you get from having sex in the woods.

It means stubbornness. President Obama has proposed a plan that would replace the sequester with a mix of spending cuts and new revenue from closing tax loopholes and limiting deductions for the wealthy. And Senate Democrats have proposed a $110 billion deficit-reduction package that included defense cuts, a minimum tax on the wealthy, and a reduction in federal farm subsidies. But Republican leadership is being stubborn about the view that any deal to avoid the sequester can’t include any new revenue from taxes. Jonathan Chait writes that among Republicans, the dominant story line of the sequester fight is that “in the face of cross-pressures, the party’s anti-tax wing has once again asserted its supremacy.”

Can you fast-forward to the end and tell me what’s going to happen, so I can go back to not caring?

Most plugged-in observers expect the sequester to kick in, in some form — though Congress may be able to pass a last-minute bill that would implement its cuts in a slightly less destructive way. Then, the question will be whether Republicans will ultimately cave on some of their demands and cut a deal. Polls show that most Americans are deeply opposed to cutting spending on most government programs, and most support raising taxes on the wealthy. But House Republicans are notoriously reflexive when it comes to opposing the Obama administration, making it kind of unlikely that President Obama’s plan (which itself represents a compromise) will be acceptable to them.

This really is incredibly boring, isn’t it.

Yes. So much so that writers and editors are scrambling to find ways to use cute animal photos and Kate Upton’s boobs to make it interesting.

So why are you making me learn about it?

Hey, you asked.