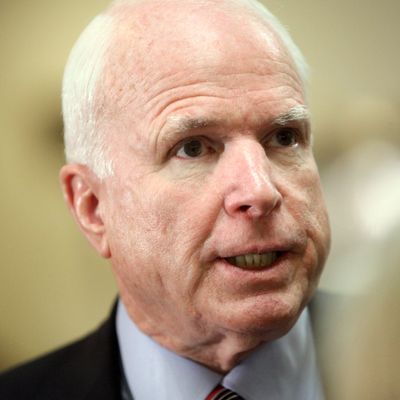

John McCain is a cranky man in general, and the latest punks he told to get off his lawn include tea-party hoodlums Ted Cruz and Mike Lee. (Addressing the latter, McCain growled, “maybe the senator from Utah ought to learn a little bit more about how business has been done in the Congress of the United States.”) McCain does not seem to be showing much remorse either. Reporters are writing stories about his increasingly vocal recriminations, and McCain is tweeting them out:

There is more going on here than just another dyspeptic outburst. McCain is displaying increasing signs of agitation with the ideological currents driving his party. His journey from orthodox Republican to the left edge of his party and back may have one more reversal yet.

The basic way to understand McCain is that neoconservative foreign policy is his ideological core. Everything else about his ideology can shift radically depending on his ambitions, circumstances, and whom he’s most angry with at any given moment. He favored immigration reform under George W. Bush, abandoned it to refashion himself as a “build the dang fence” border hawk, and, in the wake of last November, embraced it again. He fashioned himself as a modern Teddy Roosevelt environmentalist crusader during his anti-Bush phase, sponsored a cap and trade bill, but decided to run as a “drill here, drill now” conservative in 2008, abandoning his own cap and trade plan once Obama tried to pass it.

But the foreign policy hawkishness has remained constant. And the foreign policy hawks have found themselves the biggest losers in the GOP’s postelection ideological restructuring. One aspect of this change is that the party, after assailing Obama from the right, has suddenly found fertile terrain in attacking him from the left. Rand Paul’s surprise talking filibuster speech against drone use in March picked up out-of-nowhere support from Republicans of all stripes — save McCain, who lambasted him as an ignoramus.

The biggest defeat the neocons have suffered is sequestration. When Republicans signed on to the sequestration plan in 2011, as a way to get out of the debt-ceiling crisis House Republicans had instigated, defense hawks were assured the across-the-board spending cuts would never be carried out. Everybody assumed the 2012 election would settle the budget dispute, or in some way encourage the sides to cut some kind of deal. Instead, most conservatives have flipped on the question, going from decrying sequestration as a threat to national security to happily insisting they now love it and want to keep it forever and ever.

That leaves McCain and a handful of remaining committed hawks hoping for a budget deal that could reverse the sequestration cuts to the Pentagon. That fight within the party is now playing itself out in the form of a somewhat abstruse fight over budget procedure. Republicans lifted the debt ceiling last spring on the condition that Senate Democrats passed a budget and — for reasons nobody outside the party understood — hailed the return to regular budgeting as a great victory. Almost immediately after that, they figured out that this was actually terrible for them. If the House and Senate had to reconcile their budgets, that would lead to a negotiation and a compromise somewhere in the middle — which is what Obama has been desperately trying to get and which conservative Republicans have been equally desperately trying to prevent. The conservative position is that, rather than negotiate, they want to use the threat of refusing to lift the debt ceiling to extract unilateral concessions from Obama.

That’s the context for McCain’s latest spat with his party’s right wing. Lee, Paul, and other right-wingers want to prevent any budget agreement by requiring that budget talks not lift the debt ceiling. This, of course, would sabotage the negotiations before they begin — Democrats would realize they couldn’t strike any deal because Republicans would come back in the fall demanding more concessions in return for not blowing up the world economy.

And so McCain’s disagreement over what appears to be a technical point of Senate process is actually a fundamental split over the party’s approach toward Obama. The conservatives want to continue their stance of total opposition and instigating crises — the stance that has defined the party throughout the Obama era — while McCain wants to engage in compromise and negotiation. McCain’s softening stance toward Obama can be seen in other ways. He broke with his party to support the Manchin-Toomey background-check bill. He met with Obama last week and discussed immigration and budget issues.

Yesterday he lauded Obama’s foreign policy address, promising to support a rewriting of the 2001 authorization of military force. “Such legislation would be a fitting legacy for this Congress — and for President Obama,” he said. Perhaps McCain has gotten past his bitterness from 2008. Or maybe he’s just found different people to be bitter about.