It’s not exactly news that in the absence of a solution to the unemployment crisis, Americans have learned to cobble together various odd jobs to replace the full-time, benefits-included positions they once had.

What’s surprising is how permanent the so-called gig economy is turning out to be. I once thought, perhaps naïvely, that they’d be temporary measures that would fade out of favor once the economic outlook had improved. But there’s no sign of a slowdown in the creation of new and innovative ways for people to commit themselves to sub-optimal economic conditions, possibly for the rest of their lives.

In this week’s New Yorker, James Surowiecki looks at Upstart, a year-old company begun by ex-Googlers that is giving young people in the post-crash economy the chance to indenture themselves to patrons in the investor class. It does this by making it easy for users to create human-capital contracts — an agreement that says, for example, that investors can give you a lump-sum payment of $50,000 in exchange for 5 percent of your income for the next twenty years. It’s the kind of contract that could only flourish in a truly desperate economy, but Surowiecki — who finds the personal profit-sharing arrangements similar to what already goes on in industries like publishing and poker playing — isn’t all that troubled:

Upstart may succeed or it may fail, but the principle behind it is unlikely to disappear … The old way of borrowing was predicated on a world in which the job market was stable and everyone had a steady income. That world of work is changing. The way we finance it needs to change, too.

Surowiecki doesn’t say this, but the “world of work” isn’t just “changing.” Like ice floes and Miley Cyrus, its changes over time are the product of human intervention. In this case, the human error has been a jobs-destroying financial crisis, short-sighted fiscal policy, a credit crunch, and a well-funded deficit-reduction movement that has drawn attention away from the jobs crisis. If these things hadn’t happened, we might not be in the position of needing to mortgage decades of future earnings for the chance at a one-time loan. We’d work hard at full-time jobs with benefits, get fixed-rate loans when we needed to buy stuff, and keep our wages for ourselves once the loans were paid off.

You wouldn’t necessarily come away feeling a chill, though, if you read just Surowiecki’s piece, or if you saw today’s Bloomberg TV segment about TaskRabbit. The segment gives a fairly rosy vision of the new economy, complete with a bicycling TaskRabbit who makes “a few hundred bucks” by running errands for overextended San Francisco residents. But it, too, had ominous undertones, especially when the statistic that only 10 percent of TaskRabbits earn enough to make it a full-time job is casually mentioned. This is not a job-replacement service; it’s an income supplementer, and an exclusive one at that, open mostly to those who live in major cities and are digitally savvy.

Last weekend, the San Francisco Chronicle ran a story that got to the heart of the transition to a gig-based economy. The Chronicle introduces us to several “gigwalkers” who have made ends meet, barely, by doing one-off TaskRabbit errands, snapping photos of food for Microsoft, and renting out spare rooms on Airbnb. And, amid a discussion of the 40 million (40 million!) workers who may be now employed on a contingent or freelance basis, the paper drops this incredibly depressing quote, from the CEO of oDesk, a Silicon Valley gig marketplace site (emphasis mine):

“This is a real shift of where the world is working,” said oDesk CEO Gary Swart. “Today, work is no longer a place.”

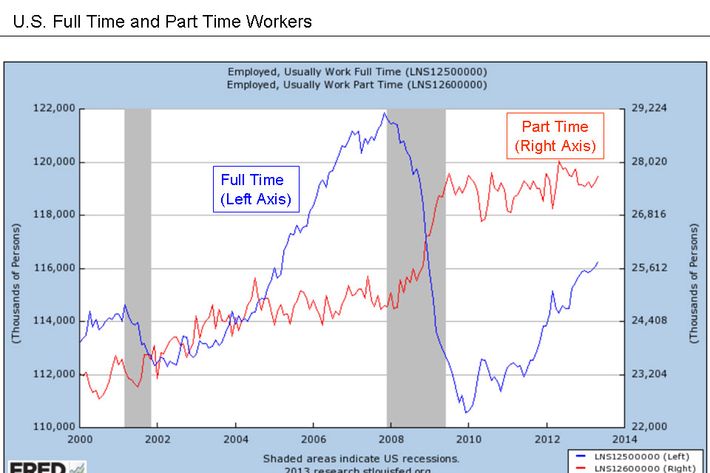

I suspect Swart means this as a good thing, but the grim reality is that permanent, place-based jobs are disappearing, and being replaced by lower-paying, part-time equivalents. It’s hard to capture the change numerically, since the Bureau of Labor Statistics categorizes temp workers, freelancers, and contingent workers differently, but we know that millions of people who used to work at nine-to-five jobs are now being reduced to part-time status (which, you could argue, still puts them ahead of those forced to go freelance).

This weekend, the web was abuzz about “Slaves of the Internet, Unite!,” a Times op-ed by Tim Kreider that drew attention to the fact that many writers who used to make a living by stitching together freelance gigs are now being asked to work for “exposure” only. Kreider’s observations about the changing economics of web journalism were depressing on their own, but they’re even more potent when you consider that it isn’t just journalism that’s being changed for the worse by the New Economy. From errands to professorships, the value of all labor is being written down, from something worth paying a full salary and benefits for to something that can be apportioned, piecemeal, to the lowest bidder.

These complaints have been leveled many times during the economic recovery. But what’s new in the conversation about the gig economy is the sense that we’re now settling into this moment, and accepting it as the inevitable future. We seem to be forgetting that services like TaskRabbit, oDesk, and Upstart were always supposed to be stopgap measures, meant to take some pain out of a struggling economy. And as we look to them for our economic salvation, our eyes wander from the kind of recovery we really need.