Yesterday, Robert Levinson, a retired FBI agent who disappeared while traveling in Iran in 2006, became the longest-held American hostage in history. He replaces my father, Terry Anderson, who spent 2,454 days in captivity before being released. My father, AP’s bureau chief in Beirut at the time, was kidnapped by a Shia militant group in Lebanon three months before I was born. I met him for the first time in December 1991, when I was almost 7.

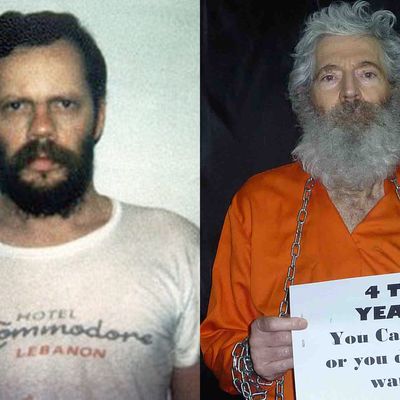

“Longest-held American hostage” — it’s a dubious honor, to say the least: the waiting, the false alarms, the images of your loved one, thin and pale, holding a hateful sign or speaking terrorist propaganda. The photos of a haunted, bearded Levinson wearing an orange jumpsuit brought tears to my eyes. The first time I ever saw my father speak, he looked just like that. I was a child, and his captors would intermittently release videos of him to the press. That was the image I carried of my father in my head for seven years; that and the picture of him from a happier time I kept under my pillow and kissed every night before I went to sleep.

My heart goes out to Mr. Levinson’s family. Unfortunately, my father’s release was not the happy ending portrayed by the media. No mortal man could have lived up to my child’s expectations of what he would be like, but he came home deeply traumatized, robbed in many ways of his capability to be the father I needed — that every child needs.

I’m a journalist now and work mostly out of Beirut, a career choice many find bizarre. I think I became a reporter partly because I wanted to feel closer to my father, on a deeply subconscious level, but also as a result of what I considered to be betrayal by the press — a betrayal I promised myself never to repeat. The media wanted a neat resolution to the saga of my father’s captivity. Viewers don’t like ambiguous endings. But there was no neatness to his arrival in my life, or my arrival in his. Events like this don’t get tied up in a bow. Some threads are torn forever; others dangle inescapably from one’s life for decades.

My father’s trauma, and its effect on my family, left me with a chronic mental illness I’m still recovering from. The men who kidnapped him stole my childhood and hijacked my adult years. They took away the brothers and sisters I could have had and forever warped the way in which I relate to the people around me. His captivity had a ripple effect that shaped my life, for better or worse.

I’ve been attempting to understand how such a thing could have happened to my family since I was old enough to form thoughts. I try to imagine what it’s like in the mind of a person who would take a man’s freedom and keep his loved ones suffering for years, robbed of their husband and father. I don’t always succeed, but I stopped hating the men who took my father years ago. I hate the circumstances that created them and the forces that tear nations apart, making it possible for people to hurt one another with such devastating casualness.

I’ll be brutally honest. As painful as this is for me to admit, I hated my father for quite some time. After he came home, I would cry at night and pray for him to disappear from my life as suddenly as he had appeared. I couldn’t comprehend why he was unable to express emotions or form a connection with me, the daughter who had worshipped his photograph for so long. The years have brought me a deeper understanding of the damage wrought by that kind of trauma, and overwhelming respect for his courage. At the time, though, it wasn’t possible for me to understand anything except the hurt I felt when he snapped at me, the frustration of wanting to be held by a man who hadn’t felt any human contact that wasn’t violent for seven years.

But I got him back. With all the mess and the misunderstandings, all the slammed doors, harsh words, and quiet tears, I can call my father today and tell him I love him, or ask him for help on a story. I can’t possibly imagine a world in which I never had him in my life.

No one understands better than me the painful limbo the Levinsons must be living in. Unable to grieve, unable to move on and mourn the passing of your loved one, because he could very well be alive. It’s a sick kind of hope, one that turns sour. I hope from the bottom of my heart it ends soon, and with his safe homecoming. But even after the cameras leave, my thoughts will be with the Levinsons, as they struggle to make sense of their happy ending.

Sulome Anderson is a journalist and author based between Beirut and New York City. She’s currently working on a book about her family’s experience. Follow her on Twitter: @SulomeAnderson.