After mulling a boycott, on Wednesday House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi finally agreed to appoint five Democrats to the special committee investigating the Benghazi attacks, explaining that the move will give Democrats more influence over the proceedings. By joining the panel, Democratic Representatives Elijah Cummings (Maryland), Adam Smith (Washington), Adam Schiff (California), Linda Sanchez (California), and Tammy Duckworth (Illinois) will be taking part in a long, and not exactly proud, American tradition. Congress has been forming special investigative committees since 1792, ostensibly to uncover the facts about serious government wrongdoing – though they often devolve into an excuse to smear the other party. As we head into another long summer of contentious congressional hearings, here’s a look back at some of the controversial investigations that led us here.

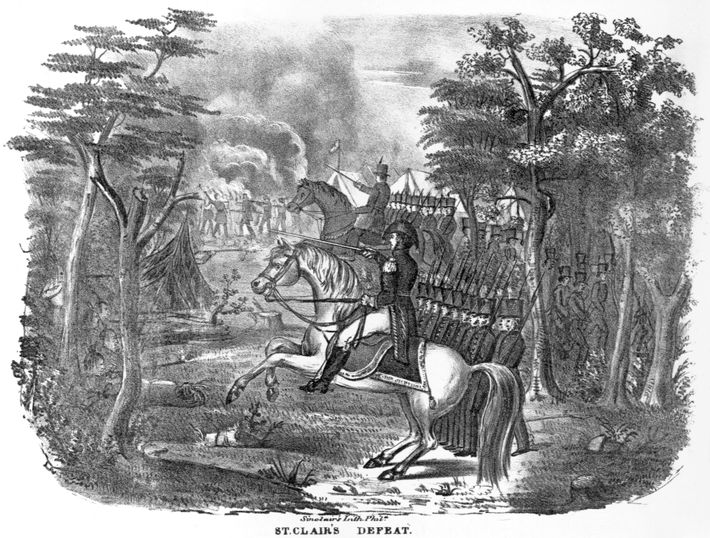

St. Clair’s Defeat

In 1792, Congress formed a select committee to investigate a scandal for the very first time. A year earlier, Major General Arthur St. Clair led an unsuccessful attack on Native Americans that left 600 American soldiers dead. It was unclear if the House had the power to investigate the reasons for St. Clair’s defeat, but President George Washington concluded that they could proceed, and agreed to provide the documents they requested. (However, he said he would not reveal information that could harm the public, establishing a precedent for executive privilege.) When the report cleared St. Clair, concluding that mismanagement by the War Department was to blame, Secretary of War Henry Knox complained that it was “founded upon an ex parte [one-sided] investigation.”

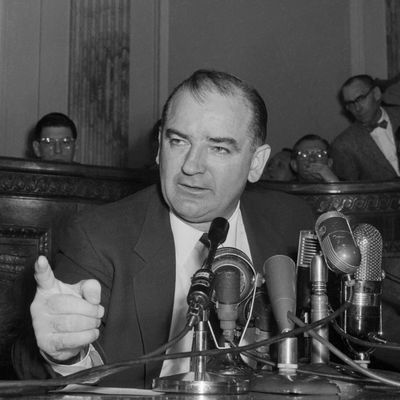

Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Committee on Un-American Activities

Originally formed in 1938 to investigate Americans with Nazi ties, the House committee eventually shifted its focused to U.S. citizens, government employees, and organizations believed to have communist sympathies. Following hearings in 1947 on communism’s alleged influence in the film industry, ten artists who refused to testify were blacklisted in Hollywood. The list would grow to include more than 300 directors, actors, and screenwriters.

Senator McCarthy conducted his own anti-communist investigations as head of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, holding 169 hearings in 1953 and 1954. Many of his targets’ careers were destroyed, and some were imprisoned. Eventually, McCarthy went too far, launching an investigation into the U.S. Army. During the televised Army–McCarthy hearings in 1954, the American public saw the two sides trade accusations for 36 days. After the hearings – which included Army counsel Joseph Welch’s famous rebuke, “Have you no sense of decency, sir? At long last, have you left no sense of decency?” – McCarthy’s popularity declined significantly.

Watergate

In the summer of 1973, a special Senate Committee held hearings to investigate the burglaries committed the previous summer, and whether President Richard Nixon’s campaign had committed “illegal, improper, or unethical activities.” The hearings were broadcast live, and 85 percent of U.S. households reported watching some portion of them. There were many major revelations during the hearings, such as the existence of Nixon’s secret White House tapes, and by June, a Gallup poll found 67 percent of Americans thought Nixon was involved in the break-in or cover-up. The evidence gathered during the Senate’s investigation led to the conviction of several Nixon aides, and the introduction of articles of impeachment, which prompted Nixon’s resignation. This is the congressional hearing every member of Congress is aspiring to when they launch a partisan investigation of the president.

Iran-Contra

Fourteen years later, America saw another summer of televised hearings about the president’s activities. Committees were formed in the House and Senate to investigate the Iran-Contra affair, and they held joint hearings from May to August 1987. The hearings turned Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North, who formed the plan to divert profits from selling arms to Iran to support Contra rebel groups in Nicaragua, into a star. After the first day of his compelling testimony, the Washington Post declared, “The day-long show proved again that Washington can still outdo Hollywood in the production of high-yield dramatic blockbusters.” The committees concluded that the Iran-Contra affair involved ”pervasive dishonesty and inordinate secrecy,” as well as ”deception and disdain for the law.” However, while the scandal was a blow to the Reagan presidency, even Democrats weren’t eager to impeach another president.

Whitewater

As Independent Counsel Ken Starr looked into the death of Vince Foster and the Clintons’ Whitewater real-estate investments (and eventually the Lewinsky affair), the Senate performed its own investigation. The Senate Whitewater Committee convened in 1995, and the hearings ran for 300 hours over 13 months, though they would prove far less successful than Starr’s efforts. The committee’s final report hinted at once instance of possible wrongdoing by President Clinton, but described Hillary Clinton as a central figure in the administration’s “pattern of deception and arrogance.”

Democrats dismissed the the findings as a “witch hunt,” and said in their minority report that Republicans were only focused on Hillary because they were unable to “tarnish the president.” “The venom with which the majority focuses its attack on Hillary Rodham Clinton is surprising, even in the context of the investigation,” they wrote. “Every act is portrayed in its most cynical light, every failure of recollection is treated as though the standard for human experience is total recall and photographic memory.”