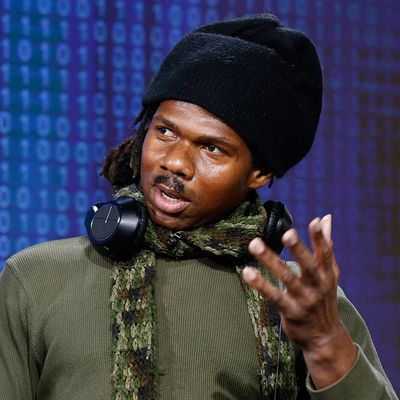

Last summer, a 23-year-old computer programmer named Patrick McConlogue undertook a modern version of the Pygmalion project. He decided to take a homeless man under his wing, teach the man to write computer code, and see whether his subject’s lot improved. McConlogue found a willing pupil in a man named Leo Grand, who was then living by the West Side Highway, and who proved to be a remarkably fast learner. By December, Grand had produced an app called Trees for Cars. The duo were covered warmly by the Today Show, and not always so warmly by the blogosphere. Soon Grand had enthusiasts from around the world and $10,000 in sales. But recently the story has taken a dark turn, or at least a human one.

Business Insider caught up with Grand and McConlogue this week and discovered that Grand never picked up the $10,000, which sits in a bank account under McConlogue’s stewardship. Something having to do with the formality of banking or the idea of possessing that much money seems to make him uncomfortable. Several times the two men have headed to the bank to set up an account for Grand so that the money can be transferred to him, but “they never made it more than a few blocks before Grand insisted on turning around.” Grand is apparently still sleeping outside. McConlogue’s view seems to be that the homeless man has a psychological block, which is almost certainly true. No doubt this has been a complicated experience for Grand. But because McConlogue approached this experiment with such explicit philosophical talk, with such explicit layering-on of the social import, it also became a kind of test for a proposition: that despite the country’s background inequality crisis, at least in the world of tech entrepreneurship, true talent can still win out. Here, at least, the meritocracy stood.

From the beginning the Homeless Coder Experiment was highly contested ground, ethically speaking. There was a lot about McConlogue that seemed naïvely romantic — he seemed to cast Grand as a modern Noble Savage. The mass-culture land of morning television fell for it. The middlebrow combat zone of web commentary despised it: “The homeless are not bit players in your imaginary entrepreneurial novella,” The New York Observer’s Betabeat blog scolded McConlogue, and they had a point. What had a 23-year-old computer programmer accomplished to allow him to condescend to another adult human being like this? “It’s up to him,” McConlogue once wrote, after describing Grand’s vivid intelligence, “if dedication is also his gift” — as if the whole messy matter of getting ahead in American life boiled down to moral sufficiency.

In some ways, this is the aspiration that has accompanied the whole episode that the Homeless Coder Experiment is part of — the strange, fascinating expansion of the cult of entrepreneurship, which has recently been filling quickly. I don’t just mean the long-standing and noxious cult of entrepreneurial success, but the more recent insistence that every man might become an entrepreneur, that entrepreneurship is part of the normal American experience rather than simply the exceptional one. Schools are adding coding to their curricula to help prepare students for computational thinking. (The first reports documenting this trend in the New York Times were quickly followed by the first Times opinion pieces calling it a scam.) Peter Thiel, the libertarian billionaire, is offering fellowships to teenagers to drop out of school to pursue more worthwhile work. The heroic language of entrepreneurship is now filtering down to even mundane occupations, so that Uber calls its freelance taxi drivers “entrepreneurs” and Washio refers to its laundry delivery drivers as “ninjas,” borrowing (as my colleague Jessica Pressler recently pointed out) a little Silicon Valley glamour.

Part of this is simple vanity arbitrage — call a cabbie an entrepreneur and maybe you get some useful and satisfied workers who otherwise would have turned up their nose at the experience. But there are also pathological strains. The Urban Institute’s Austin Nichols noticed this week that the number of businesses that have been incorporated but which fail to employ a single worker has shot up recently, so that there is now nearly one incorporated business with no one working for it for every five workers. The sheer quantity of human dreams those figures represent — fleshed out, formally registered, but never quite turned into something real — is staggering to behold. Even more startling is that all of these dreams are being funneled through the peculiar opportunistic language of entrepreneurial capitalism.

In the case of Leo Grand, the feeling that tech entrepreneurship might serve as a kind of corrective inequity was always explicit. The “unjustly homeless,” McConlogue called the kind of man he meant to help. Meeting Grand, he marveled at the homeless man’s smarts and fluency (“As I sat there becoming increasingly stunned, he rattled off import/export numbers prices on food, the importance of solar and green energy …”) In announcing his project, McConlogue wrote of “that feeling you get when you know the waiter, the cashier, the janitor is in the wrong place — they are smart, brilliant even. This is my attempt to fix one of those lost pieces.”

By any reasonable standard, the attempt has gone brilliantly. And yet the tangible benefits to Grand have not been so vast. $10,000, even for a man without a home, is not an enormous amount of money — it is about what you would earn if you worked a minimum wage job for eight months, which is to say not enough to lift a person out of poverty and not even enough to guarantee him a home.

But it may be that this was never really about monetary rewards, at least for Grand or McConlogue, or not only about them. Though he can’t bring himself to claim the $10,000, Grand has been diligently attending coding classes in Lower Manhattan several days a week. (Grand: “I actually really like coding.”) The extramaterial benefits of the experience — maybe the community (“McConlogue once asked Grand what the worst part of being homeless was. The answer? ‘It’s lonely.’”), or the intellectual engagement, or just affirmation that despite outward appearances, he had something real to offer the world — had some meaning to Grand. These rewards may not have been more important to him than the money, but they were, at least, a more comfortable fit.

I suspect something similar is at work in the cult of entrepreneurship, in the evangelical hope that every person might become one. The promise of entrepreneurism — especially vivid in tense economic times — is that work can be big enough to hold all of those dreams, of individual expression, of personal fulfillment. Whether or not you think this is an illusion and a scam depends upon whether you see entrepreneurship as basically an economic act or basically a human one. It depends, in other words, on whether you think it’s nuts for a man who badly needs money to find some meaning in being a coder but to leave $10,000 in cash sitting idle in a bank.