Recently, I spent a week on Block Island, a rustic little spot off the coast of Rhode Island. As usual, escaping the city in the summertime promised to bring a whoosh of relief from heat and bustle. But it also, for the first time, brought a twinge of anxiety about all the technological ease I’d be giving up, as there’s no Uber or Lyft on Block Island, no Spoonrocket-delivered meals or same-day Google Shopping Express trucks. These things wouldn’t even make sense there — with only a few hundred residents on the island, there would be no way to make the economics work.

Like many coastal city-dwellers, I’ve gotten used to these digital creature comforts. And while going without them for a week hardly qualifies as a tragedy, it did get me thinking about the geography of innovation, and the disparate impact of technological progress on urban centers. More specifically, I began wondering whether, at this point, choosing to live outside a major city is tantamount to opting to live in the past.

I’ve lived in big cities, in suburbs, and in rural towns. All three have their charms. But new research shows that cities are much more likely to benefit from today’s massive wave of consumer tech investment — think delivery drones, self-driving cars, and green-energy innovations. The fact that many of these technologies are being developed and deployed first in densely populated urban zones, rather than in the countryside, means that in the future, cities are going to pull further away from rural and suburban areas economically, and carry a much higher quality-of-life premium than smaller towns.

A new report about so-called “innovation zones” is one of the clearest so far on the subject of urban tech growth. The report, by Bruce Katz and Julie Wagner of the Brookings Institution, claims that while innovation used to take place in loosely packed suburban areas like Silicon Valley, innovation in the 21st century is moving into large cities, which have several major advantages:

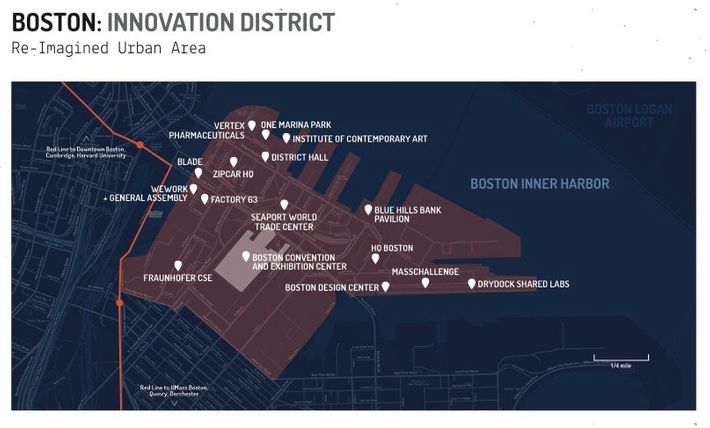

1. Physical assets. Cities, Katz and Wagner write, are filled with all the things that make for a bustling, energetic tech economy: parks, plazas, apartment buildings, public transportation, and city infrastructure that can be turned into a “living lab” to test new technologies. Many cities also have old-line industrial buildings that can easily be turned into trendy tech headquarters. In Boston, for example, the Seaport — once an economic drain on the city — has been repurposed as a tech hub, complete with companies like Zipcar and co-working spaces like General Assembly.

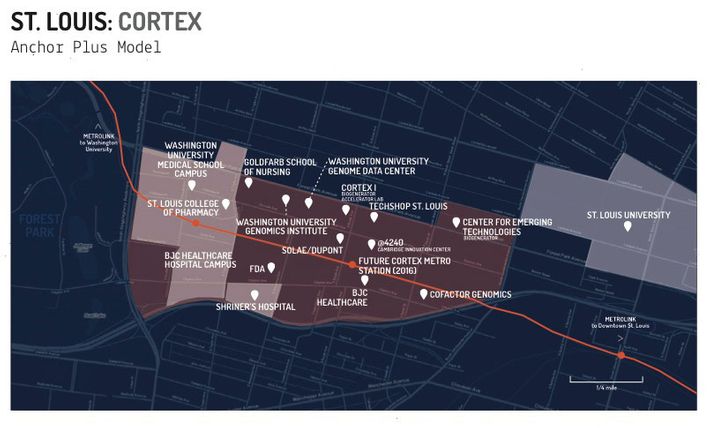

2. Economic assets. In cities, you often find built-in advantages for those hoping to take part in the tech economy. Chief among these are so-called “anchor” assets like large research universities, as well as start-up incubators, accelerators, and job-training firms. Innovation districts also have what Katz and Wagner call “neighborhood-building amenities” — coffee shops, restaurants, bars, hotels, and local retail stores, all of which make them more attractive places for people (especially young, creative people) to live and work. A good example of how these assets help create an entrepreneurial climate is St. Louis, whose tech corridor is built around St. Louis University, Washington University Medical School, and several other hospitals where, presumably, cutting-edge research is bleeding over into the zone’s other tech companies. (Katz and Wagner call this the “anchor-plus” model.)

3. Network effects and cross-pollination. It’s not just what lives in cities that makes them attractive spots for tech companies — it’s who lives in them. It’s no secret that cities with a large population of young, educated people all strongly tied to each other through a central institution like a university tend to do well economically. But Katz and Wagner write that a city that does well at creating weak ties — cultivating not just friendships, but relationships with friends of friends, and friends of friends of friends — is more important than previously thought. “Weak ties provide access to new information, even novel industry information, new contacts, and new information on business leads that are outside of existing networks,” they write. Accordingly, cities that hold hackathons, tech breakfasts, and other networking functions are better positioned than those that don’t.

Network effects also explain why tech companies tend to come in clusters. (Amazon’s Seattle headquarters, for example, is surrounded by dozens of smaller outfits.) “In today’s economic landscape, no one company can master all the knowledge it needs, so companies rely on a network of industry collaborators. This, in turn, has led to a shift in where companies and support organizations locate.”

4. Density as a service. There’s another important contributor to the bright future of cities that Katz and Wagner don’t mention. Namely, many of the tech start-ups that are bringing on-demand services to large cities have business models that only work in densely populated urban centers. You couldn’t run Uber in rural Tennessee because you need a constant supply of people looking for rides and a constant supply of drivers willing to give them. For a delivery service like Google Shopping Express to stand a chance of being profitable, each delivery truck needs to be loaded to the brim and make multiple stops along a route — dropping off one item at a time won’t work.

As cities grow, their advantages of scale will grow, too. From 2012 to 2013, U.S. metropolitan areas of more than 1 million people grew twice as fast as cities with fewer than 250,000 residents. Downtown areas — the places where density is highest — are growing even faster. And millennials, who both start tech companies and form much of the consumer base for tech products, are flocking to cities in record numbers. The convergence of these trends means that large cities are not only going to get bigger in the coming years, but better.

5. Special status. Strangely, I didn’t come away from Katz and Wagner’s report thinking that New York City is beating cities like St. Louis and Boston when it comes to innovation, despite its massively bigger population. That’s because another important ingredient in innovation is recognition. Katz and Wagner couch this point in jargon — “innovation districts ultimately need to be treated as a unified asset class that recognizes the synergistic effect of disparate investments that strengthen and reinforce each other’s value” — but what they’re saying, realistically, is that a tech community that is treated by its home city as a special, treasured thing is more likely to succeed than one that isn’t. In St. Louis and Detroit, tech companies are seen as a godsend. In New York, they’re just one more industry. And although New York is trying to rebrand itself as a tech city, the size of other industries in the city (e.g. Wall Street) means that techies will likely always be small fish in a big pond.

The takeaway? Move to a city.

Technically, innovation zones don’t have to be located in cities. (North Carolina’s Research Triangle Park, for example, was an early innovation zone built in the suburbs.) But because of their density, cities are much more likely to become petri dishes for innovation. Google’s self-driving cars — which require the roads they drive on to be specially scanned beforehand — will be taught the layout of cities like San Francisco and Seattle long before they come to the countryside, and Amazon drones (which will reportedly have a ten-mile radius) will come to dense urban cores long before they’re deployed in the burbs.

The fact is that lots of brand-new technology depends on population density, sizable capital investment, and a large user base — the very things cities provide. And as the number of city-only services grows, so too will the quality-of-life gap between cities and non-cities. Which is why, if you live outside a city and you care about having access to the fruits of the new economy, you should start packing your bags today.