At 26, Ritchie Torres is both the youngest member of the New York City Council and the first-ever openly gay councilmember from the Bronx. These days, he is partway through a very challenging self-assigned mission: To build a community center for gay senior citizens in his home borough. Already, he has secured some funding for the project, which he sees benefiting “the most underserved part of the most underserved New Yorkers.” The Bronx is the only borough without a gay community center of any sort.

Asked what he envisions, Torres pulls out his smartphone and shows an image of the Bronx River Art Center, with the letters BRAC written across the sides of the structure. “Picture that,” he says, “at Fordham and Bainbridge, in the geographic heart of the Bronx, the cultural heart of the Bronx, the commercial heart of the Bronx — with big letters like this: PRIDE.” He hopes to see it built in 2015.

There are about 100,000 gay senior citizens in New York, roughly 32 percent of whom live in poverty, according to Service and Advocacy for GLBT Elders, a national group that opened the nation’s first publicly funded, full-time gay senior center, the SAGE Center, in Harlem in 2004 and a second location in Chelsea two years ago. There are 9,900 gay seniors living in poverty in Brooklyn, 8,700 in Queens, 6,300 in Manhattan, 5,400 in the Bronx, and 1,800 in Staten Island, according to the group. A 2010 study found gay male couples have roughly double the poverty rate of their straight counterparts.

“Manhattan doesn’t define LGBT New York,” said Kira Garcia, a spokesperson for SAGE. “Unfortunately, we see many gay elders go back into the closet as they age. Many retirement communities and nursing services are not welcoming or accommodating.”

“I see the Bronx as the Bible Belt of New York City,” says Torres. “It’s tough. It’s hard to be gay there.” It’s a borough where people still use clunky half-closeted phrases including “down low” and “men who have sex with men.” Torres says he tries to represent “LGBT people who live outside the gay meccas of New York.”

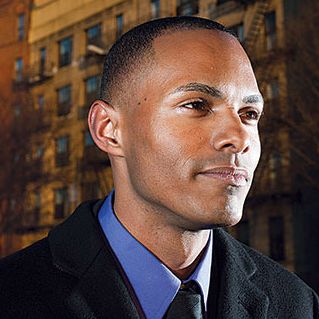

On his first-ever trip to Fire Island this summer, Torres says he was astounded by “a sea of shirtless men, which” — he paused — “you just don’t see in the Bronx.” But even as a single, handsome twentysomething, he says he spent his time there on his Kindle, reading The Economist — a self-described “old-soul.”

He describes a great sense of gratitude toward gay seniors and the sacrifices they made and the collective pain they endured. “Let’s say you’re 60 years old,” he says. “That means you were 30 in 1984, when AIDS destroyed this city.” Only a decade or so prior to that, he notes, homosexuality was still characterized as a mental illness.

Torres came out in 2004, at age 16, and credits an openly gay high-school teacher for inspiring him. It was a school, Torres says, “where we had 5,000 students and maybe 5 showing up to the gay-straight alliance meetings.” Even on a recent visit to a Bronx high school, he recalls that a girl asked what it was like to be “openly … y’know,” to which he asked, “Openly 26?”

“I once felt sexuality was a private matter,” he says. “Whose business but mine is it? But after watching The Normal Heart, I found the value of visibility. Invisibility can be deadly.” His district of Fordham, he notes, has a lower HIV infection rate than Chelsea, but a higher mortality rate. “When I’m knocking on doors, I’m advocating what I see as the greater good. None of us should fear dying alone. That’s a huge fear for many gay people, including me.”