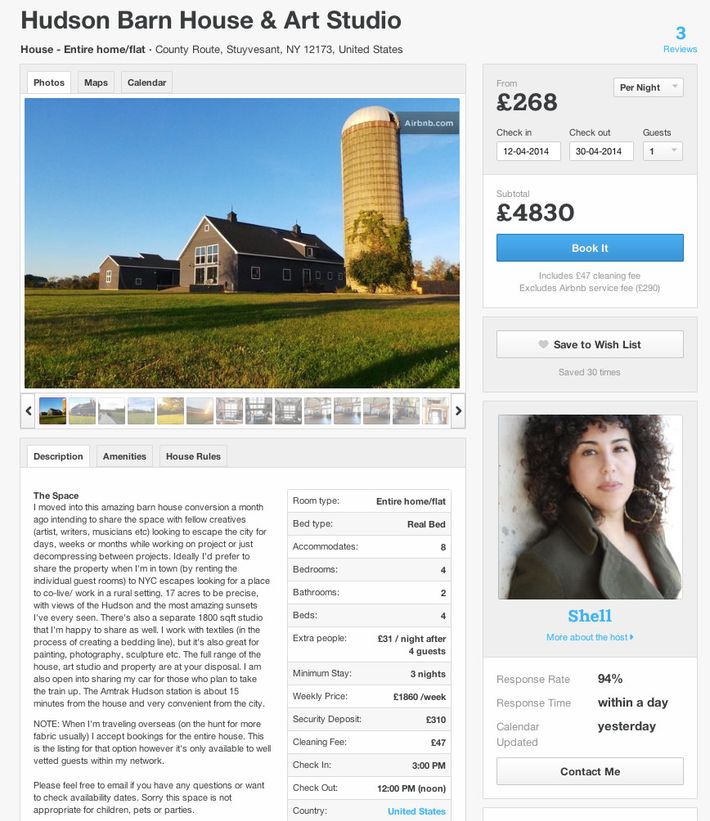

In late 2013, when Christopher Griffith moved overseas for work, he leased the renovated 1880s Dutch barn he owns in Stuyvesant, New York, less than three hours from the city, to a young fabric designer for $4,000 a month the old fashion way. “I’m renting this because I’m associated with artists and need a full studio,” Griffith says his new tenant told him at the time, warning that her “artist friends from around the world would show up and collaborate.” He thought that sounded charming.

But what Griffith didn’t realize — not bothering to wonder about how a textile artist could cover a rent like that — was that Michelle Martinez, known to the Airbnb community and anyone who’s since seen her in the start-up’s ads as simply “Shell,” wouldn’t be around much. While she was gone — say, in search of fabric in South Africa — Shell was something of mini share-economy mogul, renting out the barn (and her other leased properties) to help cover her monthly payments, in direct violation of her lease. “Friends are one thing,” says Griffith now. “Groups of social-networking strangers is a completely different ball of wax.”

Martinez insists it was simply a misunderstanding. “I thought I was very clear to Christopher. I explained my whole life and the concept of what I was doing and he seemed very keen on it,” Shell says of the barn fight. “In hindsight, I look back and go, ‘Gosh, maybe I should have communicated better.’ But there was never an intention to do harm.”

Griffith figured out his own barn was being advertised on Airbnb when he received a message from LinkedIn asking if he knew Martinez, listed there as a former real-estate agent and the founder of something called Shell’s Brooklyn Loft. Neighbors had mentioned seeing strangers around his place upstate, and suddenly something clicked. “I looked up barns in the area and my place came up at $475 a night,” he says. The barn was also listed on Airbnb competitors TripAdvisor, FlipKey, Dwellable, and Outpost. “I was like, ‘Of course! How could I be so stupid? How could I not have known?’”

He’s not the only landlord who feels like he’s been getting duped. As Jessica Pressler explored in a recent New York magazine story, the war over Airbnb in New York has turned extremely personal as the sharing-economy “movement” clashes with locals’ deep-seated sensitivity about rents and real estate. “It took Airbnb more than two years to put up a notice warning people that listing apartments may be against the law or their building regulations,” Pressler noted of the multi-billion-dollar company. “Even after it did, a lot of people have simply ignored the warnings, either out of indifference to Terms and Conditions or loyalty to the cause.”

Shell is all about the cause. Her primary residence is a leased six-bedroom, 5,000-square-foot Brooklyn loft (“great for dinner parties, brunches, 3 simultaneous scrabble games, all sorts of craft projects”) that she lists on Airbnb for $750 a night (sans access to her bedroom), or in different permutations depending on where in the world she is or who wants to stay. “This is my personal home which I live in and share with individual travelers, groups and creative companies alike,” she explains in the listing. “I’m a collaboration junkie and a share economy super user. So I’m open to creative ways of sharing my space and I like to be involved with the people I share or rent my space to. It’s nice to know the loft is in good hands, being taken care of as I would, and with consideration of my neighbors.”

During Hurricane Sandy, Shell put up displaced victims and FEMA workers at the loft for free, helping to win the polarizing company some favorable PR. She also happens to be a power user: According to her 276 guest reviews on the site dating back to 2010, Shell also rents out a place in Puerto Rico and a ground-floor apartment in Brooklyn. (“In order to comply with NYC laws, I only sublet this apartment for stays that are 30 days or longer,” she warns in the latter listing.) In addition to the barn, there was once another place upstate, in nearby Rhinebeck.

As a result of her loyalty and good Sandy deed, Shell was asked by Airbnb to star in its New York–loves-us ad campaign, which was shot over the summer, a few months after she was evicted from Griffith’s place in exactly the kind of fight Airbnb wants to avoid being associated with. The company, she says, knew about her situation, and Shell casually name-drops “Joe and Brian” — Airbnb founders Joe Gebbia and Brian Chesky — in conversation. “They know who I am as a host,” she says.

Martinez says only a handful of people stayed at the barn while she wasn’t there (her account has four barn reviews) and that “it was always very mellow.” It may have been “jarring” for the owner to see his home listed, Shell admits. “He might have had this impression: ‘She’s making money off of me!’” That’s not true, she insists. “I didn’t make any profit.”

She did, however, rent the place out for a wedding that occurred after she was served eviction papers. “They paid me, but they didn’t pay anything more than the normal rate,” says Shell. “They didn’t pay for a wedding. It was less people than I ever had for a dinner party.” Regardless, seeing photos of strangers getting married inside his home left Griffith seething.

Attempts to report Shell’s rule-breaking to Airbnb only resulted in more frustration. “Airbnb is an online platform and does not own, operate, manage or control accommodations, nor do we verify private contract terms or arbitrate complaints from third parties,” the company told him after he reported the misconduct. “We do, however, require hosts to represent that they have all rights to list their accommodations. For security reasons we cannot divulge exactly what actions we will take but I assure you that we will review said user’s account and act such a way to uphold our Terms of Service.”

“I got absolutely nowhere. Nowhere,” says Griffith, who’s forced to confront his bad experience every time he sees Shell on those subway ads as a model of Airbnb’s share-everything (even if it isn’t yours) ethos. “Airbnb does pretty poor vetting that they’re going to throw her up as [one of the poster children] for their campaign,” he says.

In a follow-up, the company informed him, “Although we will not verify, evaluate or arbitrate the terms you identify, we will provide a complete copy of your complaint to the host and we will ask them to remove their listing.”

Shell, of course, had already been kicked out by then, and is now sticking to Brooklyn, where her loosely defined communal vibes are more tolerated, at least for now. “It’s not just Airbnb,” she says. “It’s a lifestyle.”