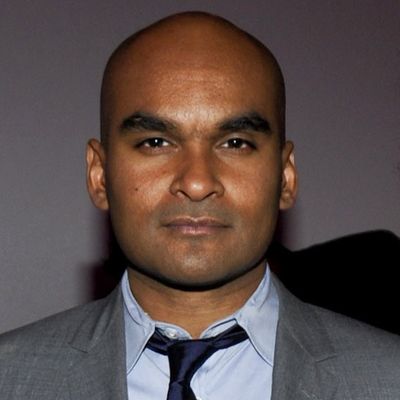

A few weekends ago, Reihan Salam threw a Thanksgiving-themed potluck for friends. The conservative writer and newly named executive editor of the National Review has always been drawn to high-density neighborhoods, but recently he moved to a relatively quiet carriage house in Dumbo, near Vinegar Hill. Guests milled about the adjoining courtyard, which Salam describes as having a “Melrose Place kind of feel,” and inside his two-bedroom home, which is decorated in primary colors, with mismatched furniture, large prints of paperback-book covers, and a William F. Buckley poster. Salam, who often favors fitted suits but was wearing a sweater, scarf, and beanie, all various shades of gray, spent much of the party facilitating introductions. Around the courtyard he went, connecting people who didn’t know each other — writers and lawyers and anthropologists and screenwriters — in remarkably flattering prose. “He introduces you, or anyone he’s friends with, and you feel like you’re being given the Nobel Peace Prize,” says Mina Kimes, a friend of Salam’s who writes for ESPN the Magazine. “It’s kind of embarrassing. But it’s also wonderful, and he does it for everyone.”

You could be forgiven for observing this scene and thinking you’re watching the work of a smooth operator: This sociability has helped make Salam — who is also a Slate columnist and CNN contributor — the favorite conservative of many liberals. In a professional network of strivers and cynics, it has also made him a source of endless fascination, from those who don’t trust his extreme extroversion to those who wonder, Does he really believe this stuff? He has tried to lay out ways that the GOP can better appeal to families like the one he grew up in. But he’s also called for an end to automatic birthright citizenship, defended Sarah Palin, and said he believes in repealing Obamacare, even though the party hasn’t lined up around an alternative. A conservative wonk who seems more at home in the Brooklyn literary scene than the Capitol Hill Club is a curious choice for a magazine used to setting the agenda for policy-makers on the right.

“Our line of work attracts people who are professional haters and I think that’s not a natural mode for me,” Salam says. “There’s a part of me that does like to mix it up and argue, but there’s another part that recognizes that it’s not actually the best impulse, and you learn a lot more from listening to people than talking at them.”

“In this world of policy nerds, almost everyone is an introvert,” says Yuval Levin, founding editor of the conservative quarterly journal National Affairs. “While they’re talking to you, you get the sense that they just can’t wait to get back to their computer. That’s just not true of Reihan.”

It’s a trait Salam’s shown since his first days in the hypercompetitive world of Stuyvesant High School. “He has an unusual combination of a voracious intellectual appetite paired with a really earnest interest in other people,” says his friend, Chris Park, who’s known him since they met at summer camp as teenagers. “It’s not purely a bookish curiosity.” The child of Bangladeshi immigrants who came to the United States in 1976, he was born in Park Slope, but his mother and father — a dietician and an accountant — raised him mostly in Borough Park and Kensington. His parents had very different lived experiences from their children. “They didn’t have super-intellectual jobs and they were people who also by virtue of being immigrants didn’t have huge networks, but they’re naturally friendly.” His mother, he says, is “someone who has a lot to say. I definitely know her life was partly constrained by being a woman, by being someone who was downwardly mobile moving from one society to another, and also being in survival mode. For both of them I think a lot of it was figuring out how to navigate a new place and being responsible and meeting obligations.”

Two events in Salam’s young life marked his entry into the world of ideas. One was when he was nine, had just seen Tim Burton’s Batman (the one with Michael Keaton), and started reading a Newsweek cover story on Batmania and thought “I am experiencing ‘Batmania!’” It got him into other magazines and newspapers they had lying around the house. The other was being tossed into the churn of Stuyvesant, where he had to learn to “be a good talker and negotiate things,” without having his hand held.

Salam found he was good at that. James Carmichael, a writer who met Salam in homeroom on the first day of high school, remembers walking the halls with him, thinking, “’Man, he’s got a lot of stuff to talk about.’ He always had this kind of simmering to feverish intensity, depending on the topic, this animation about him. In high school, that was totally the thing he was known for.” Jesse Shapiro, who was on the speech and debate team with Salam, remembers former Labor Secretary Robert Reich coming to speak at their school. Salam stood up during the question-and-answer portion and quoted his book, The Work of Nations, back to him. At the time, he considered himself a liberal: A Newsweek article from 1997 quoted Salam, champion of the school’s speech and debate team, saying that his ambition was “to be a ‘rabble-rouser’ in the cause of economic justice.”

But after high school, his thinking began to change. He spent a year at Cornell before transferring to Harvard, where he threw himself into theater. There, says his friend Min Lieskovsky, he developed an idiosyncratic set of interests, including social-science research, contemporary psychology, classical social theory, obscure West Coast rap, Russian and Eastern European science fiction, and the art of mix-tape making. (A similarly diverse mix now animates his entertaining Twitter feed.) He also began thinking of himself as a conservative. There was no single moment that crystallized it, but Salam became a big fan of Andrew Sullivan and later David Brooks, and agreed with a lot of what they had to say. “I thought of myself in high school as being liberal, but I was very skeptical of anything that liberals were strongly in favor of.” He found that he was more interventionist in his foreign-policy views than most liberals, and more skeptical of racial preferences in university admissions, for example. “By the end of college, my thinking had evolved. I was like, ‘Oh, maybe I’m not a really strange liberal, maybe I’m just not a liberal,’” he says. “Being a conservative and I.D.-ing that sort of way opened up a lot of things for me, intellectually.”

In 2008, Salam wrote a book with Ross Douthat, his former roommate and now a New York Times columnist, called Grand New Party: How Republicans Can Win the Working Class and Save the American Dream. In it, they argued that the GOP hadn’t given working-class voters reasons to keep voting for it, and argued for major tax reform that would, among other things, vastly expand the tax credit for children, create subsidies and pension credits for stay-at-home mothers, and make tax rates lowest for people entering the workforce and families with young children.

“I like the idea — I don’t always live up to it — but I like the idea of someone who is trying to translate for people who share my views,” he says. “I hope that it’s useful for them to have someone who is kind of trying to translate people with whom they disagree and vice versa. But that translator role, it’s almost designed to be a magnet for contempt.” Salam has his critics, although “contempt” might be too strong a word for their views on him — the main critique is that he’s far too willing to assume good faith in elected Republican officials who’ve done nothing but obstruct the president on important issues like health care. “If conservative health wonks really cared about health reform, wouldn’t they be exasperated w/ GOP electeds [sic] for never following through?” Josh Barro, a former reformist who has taken on the party more forcefully, wrote in an exchange on Twitter with Salam last year.

“Reihan assiduously avoids taking a firm stand on much of anything, so accuracy is inapplicable,” wrote Helen Andrews, a columnist for the religion and politics journal First Things.

If liberals sometimes doubt his sincerity, translating his pop-culture-loving, cross-ideological worldview to William F. Buckley’s wonky conservative fortnightly could test the patience of conservatives. Recent National Review encounters with lowbrow culture have involved these sorts of statements: “Millennial politics, like Millennial humor, largely consists of a hermetically sealed, self-referential universe, something like T. S. Eliot’s ‘penny world,’ in which the rules of discourse and intellectual conformity are enforced with a self-righteous ruthlessness beyond anything to be found among the relatively liberal Victorians,” as one of the magazine’s star writers, Kevin Williamson, wrote in an article about millennials paying the price for their support of Obama. When I asked Rich Lowry, the magazine’s editor, what kinds of pieces he was looking for Salam to commission, he cited two recent examples: one on the climate-change movement being similar to the unilateral disarmament movement in the 1980s and another on why the United States should retaliate against China on trade. It requires a lot of rhetorical gymnastics to defend the ideas and actions of the right to the kinds of people who show up at his parties, and vice versa, and Salam sometimes seems at pains to do it. But he is ever loyal to his team — be they the Stuyvesant kids he grew up with, or the ideological allies he works with now.

“If I had to pick one cardinal virtue, it would be his intense loyalty to people he perceives to be on his team,” says John Mangin, another longtime friend. “He is very much a team player, always looking out for his group of friends or his professional network. I’m constantly trying to get him to sell out one of his colleagues — he will not do it. You could waterboard him to try to get him to admit that a Bill Kristol tweet is stupid. He will not do it.”