Jeb Bush has doggedly defended his brother’s presidency, but last week he seemed to offer one unabashed criticism: little brother spent too much money. “I think that in Washington, during my brother’s time, Republicans spent too much money,” Jeb Bush said, when asked to differentiate himself from the 43rd president. “I think he could have used the veto power — he didn’t have line-item veto power, but he could have brought budget discipline to Washington, D.C.”

This sounds like a criticism of George W. Bush. It’s actually a dodge Republicans have used to avoid coming to grips with the failure of their party’s domestic agenda.

The centerpiece of George W. Bush’s economic agenda was regressive, debt-financed tax cuts. Republicans argued that the Bush tax cuts would not harm the federal government’s long-term fiscal position. Bush argued that eliminating the budget surplus would prevent excessive spending. “In my judgment what’s risky is to leave a lot of unspent money in Washington, because guess what’s going to happen. It’s going to be spent on bigger federal governments.” He also insisted that tax cuts would produce faster growth, leading to more revenue. Indeed, Bush insisted this actually happened, asserting well into his second term, “You cut taxes and the tax revenues increase.”

When Bush’s economic program instead turned the projected surplus into persistent deficits, conservatives did not concede they had failed. Instead they blamed Bush for allowing spending to get out of control. Of course the tax cuts had been sold as a way to prevent this very outcome. Conservatives simply shifted from claiming tax cuts wouldn’t lead to deficits because they would prevent excessive spending to claiming tax cuts hadn’t caused the deficit because the true culprit was excessive spending.

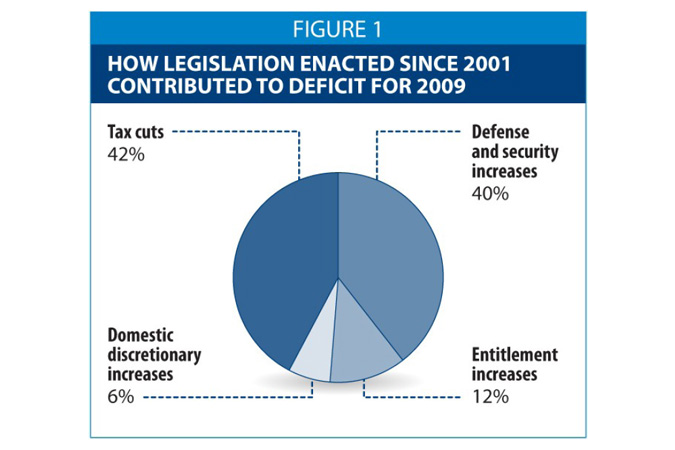

Not only did the new conservative attempt to shift blame from tax hikes onto spending undermine the original rationale, it presented a wildly distorted account of what actually caused the deficit. It was not “big spenders” defying the right who produced deficits. It was that Congress enacted the very policies conservatives were demanding: tax cuts plus more spending on defense. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities broke down the legislative causes of higher deficits under Bush, and virtually all of it was the result of policies conservatives had demanded:

Indeed, Bush himself repeatedly used this line during his own presidency. He attacked Congress for “acting like a teenager with a new credit card” and vetoed bills to increase domestic spending. When Jeb Bush and other Republicans blame George W. Bush’s indulgence toward Congress for Bush-era deficits, they’re not actually indicting his administration. They’re making the same argument Bush himself used.

Indeed, the striking fact about the Republican Party is how little it has questioned Bush’s economic program. The central tenets of Bush-era economic doctrine remain as firmly entrenched as ever. All the Republican economic proposals combine deep tax cuts, higher defense spending, and a general refusal to accept that revenues must bear some long-term relationship to likely outlays.

The party’s disposition toward Bush’s Iraq War has attracted deep (and warranted) scrutiny. Its disposition toward Bush’s economic policies has not. Despite their bellicose rhetoric, none of the Republican candidates are actually proposing to recapitulate his regime-change policy, in Iraq or elsewhere. It is in domestic policy where Bush-era dogma remains completely unreconstructed.