The Ugly Story of a Tea-Party Suicide That Left the Right Reeling — and Pointing Fingers

The aftershocks of Mark Mayfield’s death in Mississippi.

aftershocks

of a

tea-party

suicide.

One evening several years ago, John Mary was up late reading a local blog when he came across a comment from a man who said he lived in Gulfport, Mississippi. The commenter had been watching his kid mow a relative’s lawn, he wrote, when a couple approached the boy and asked if he could cut their grass sometime. The commenter recognized the man. It was Senator Thad Cochran, he wrote, and the woman with him sure as hell wasn’t his wife.

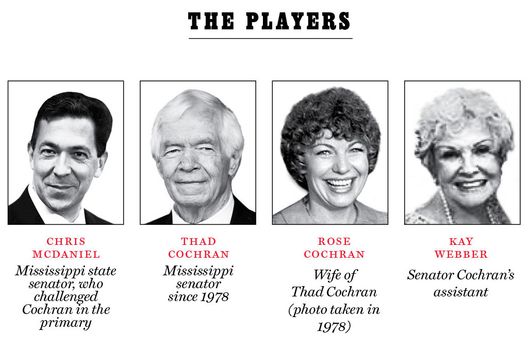

The gossip stuck with Mary, a 62-year-old from Hattiesburg, about 70 miles north of Gulfport. But he didn’t think much of it until last year, when a young conservative state senator named Chris McDaniel decided to challenge Cochran in the 2014 Republican primary.

Mary, who has wispy hair and a beard, all of it white except for his eyebrows, had an intense interest in politics. He tweeted under the handle @DaRinoHunter. His Twitter bio read: “CONSERVATIVE!! In a world filled with fakes and frauds we take seriously the job of sorting through the clutter to out the imposters OUT THE RINO’S.”

To Mary, Cochran was a classic Republican in name only. First elected to the Senate in 1978 and sometimes referred to as the “king of pork,” Cochran was known as an able deliverer of federal funding to his impoverished state. It was a skill that had been considered a virtue — until the tea party came along and made reining in the national debt a pillar of its insurrection. In October 2013, Cochran sided with party leadership to raise the $17 trillion debt ceiling, ending a 16-day government shutdown. McDaniel entered the race the next day. “I’ve got 17 trillion reasons not to compromise,” he declared at his first campaign rally.

Before he announced, McDaniel was considered one of the party’s brightest prospects. “Prior to this race, he was viewed, even by what you’d call the Republican Establishment, as an obvious up-and-comer in the Republican Party,” says Geoff Pender, the political editor of Mississippi’s largest newspaper, the Clarion-Ledger. But soon enough the party found reasons to worry that he wasn’t ready for prime time. McDaniel, who was born the same year Cochran was elected to Congress, hosted a Hattiesburg talk-radio show called “The Right Side” on WMXI 98.1 before winning a State Senate seat in 2007. The program provided plenty of ammo to the Cochran campaign. In April, The Wall Street Journal published an old clip from McDaniel’s radio show in which he promised if taxes were ever raised to make reparations for slavery, he would not pay them, and pondered aloud the meaning of “mamacitas.” BuzzFeed published audio of him saying, “I’m not even sure Janet Reno was a woman. You’ve got to put things in perspective here. When I hear ‘woman,’ I don’t think Janet Reno … for some reason. I don’t think Rosie O’Donnell, either.”

To the GOP Establishment, McDaniel threatened to be a repeat of a dynamic that had played out over the past two election cycles, when upstart candidates, including Sharron Angle and Richard Mourdock, won Republican primaries and then self-immolated in the general election, giving away seats to their Democratic opponents. In 2012, one of the most endangered Democratic senators in the country, Claire McCaskill, was able to keep her seat in large part because her opponent, Todd Akin, told a radio host, “If it’s a legitimate rape, the female body has ways to try to shut that whole thing down.” “One of the lessons of the Todd Akin disaster is that Democrats will not hesitate to tie the statements, behavior, and controversies of one Republican candidate to all Republican candidates,” a spokesman for the National Republican Senatorial Committee told the Washington Post. “This is the kind of stuff that the producers and hosts of MSNBC daytime programming salivate over.”

Mississippi’s political machine quickly lined up behind Cochran, one of the most senior lawmakers in Washington and the first Mississippi Republican elected to the Senate since Reconstruction. Almost everyone in the state who has been involved in Republican politics has some connection to him, particularly Haley Barbour, the former governor and Republican National Committee chairman turned megalobbyist. Barbour chaired Cochran’s first Senate campaign as a young lawyer in Yazoo City. For the 2014 campaign, one of his nephews, Austin, was a senior adviser; another, Henry, ran a pro-Cochran super-PAC. All of the state’s major officials as well as its entire Republican congressional delegation lent their support to his campaign. The Chamber of Commerce eventually contributed more than $1 million to his reelection, and his Senate colleagues donated to his leadership PAC.

In interviews, Cochran, who is 77, seemed to hardly know there was a tea party. “The tea party is something I really don’t know a lot about,” he told reporters more than once. Still, his campaign’s response to his challenger was swift and brutal. McDaniel had vowed not to go negative against Cochran, but he was quickly being buried under a barrage of attack ads, many of them coming from third-party groups. Pender noted that Cochran’s campaign “for weeks had a series of attack ads hitting McDaniel. McDaniel’s only official campaign ad so far is a positive piece, ‘Mississippi is my home,’ that doesn’t attack Cochran.”

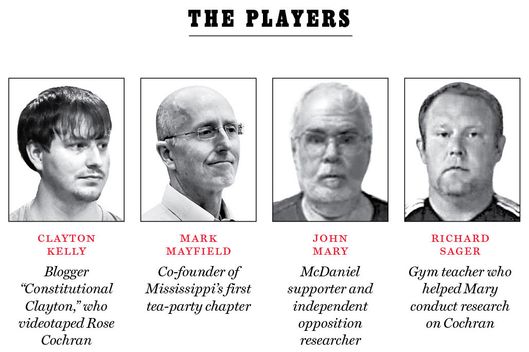

Mary was frustrated by McDaniel’s lack of response and decided to act. He knew the candidate personally from McDaniel’s days hosting “The Right Side,” where Mary had also served briefly as a host. Through another host on the show, Mary was introduced to Richard Sager, a local gym teacher and father with a knack for research who posted under the name @RedAlertMS. The two began digging online for dirt on the senator. Cochran’s wife, Rose, had been in a nursing home with early-onset dementia since 2000. When Mary searched Google Images for “Thad Cochran, wife,” instead of Rose, up popped photos of Cochran’s 76-year-old executive assistant, Kay Webber.

Mary and Sager searched Webber’s property records and found that she had a home in Gulfport, where the commenter who had spotted her and Cochran lived. They also found that Cochran had listed his Washington, D.C., residence on official government forms as the basement apartment of a home owned by Webber. They began researching Cochran’s congressional travel and found that Webber had accompanied him on 33 trips, many overseas. They were convinced that the affair was real, and they had an idea of how to prove it. If they could find one photo of his wife, to show that it wasn’t the woman he was so frequently appearing in public with, they would expose Cochran as a liar.

Another activist Mary knew on Facebook told him about a blogger named Clayton Kelly. He described Kelly as a conservative journalist with a growing following who might be able to help them circulate their anti-Cochran research. Soon Mary and Kelly, a 28-year-old libertarian who blogged under the name Constitutional Clayton, were chatting and sometimes arguing about politics. Eventually, the conversation turned to getting a photo of Rose Cochran in her nursing home.

Mary: r u here?

Kelly: hey

Mary: we need you to have no more contact with the campaign … what we are going to do will be EXPLOSIVE … the other side will be hunting for ANY connection to you … call me Mr Paranoid

Kelly: right. Chris said he would help me in any way so I immediately ruled out an interview in order to not have that tie

In another chat, Mary said he was planning something that would “CHANGE EVERYTHING.” “I am not about to discuss it here or anywhere,” he wrote to Kelly. “Suffice to say it will blow ur mind.” A few days later, he followed up:

I need you to call me it is URGENT

Mary sent a link to the Facebook page of Mark Mayfield, a well-known attorney from a Jackson suburb, who was active in local Republican politics both as vice-chair of the Mississippi tea party and a member of the local Republican executive committee. His recently deceased mother had lived in the same nursing home as Rose Cochran.

Mary: I would NOT communicate with him on his page … just talked with him it will be sometime next week … he has the funeral to deal with

Kelly: i just talked to him …

Mary: any word on the adventure … getting the pics/video is hugely important

A few days later, Mary asked, “Did you get a call?”

Kelly: Yep. with details. Got all written down

Mary: OK ... you ARE THE MAN ... REMEMBER CALM AND COOL AND DISCREET

i have NO idea what the call said ... i was not informedd

Kelly: Details on the layout of the place and what I can expect … I have a virtual layout in my head. Got all the info I need and some.

Kelly told Mary he planned to go to the nursing home on a Sunday after church. He made two failed attempts. “I know we still have time. But I am starting to get antsy when I see Thads bullshit attacks on Chris,” he wrote to Mary. “He just sits there and takes it. But that is the moral high road.”

On Easter, Kelly entered St. Catherine’s Village, a sprawling retirement community set on 160 acres of rolling pasture. A security guard held the door open for him, his attorney Kevin Camp says. Kelly took the elevator to the second floor, entered Rose Cochran’s room, held his cell phone over her bed, and took a short video. A few days later, Kelly posted an anti-Cochran video about the alleged affair to YouTube, including a still frame of Rose Cochran in her bed.

The video was online for less than 90 minutes. Just as it began to attract attention, Kelly removed it from the site. He told his wife, “the big man,” presumably McDaniel, ordered it taken down. On May 16, three weeks after the video was posted, Kelly was arrested and charged with felony exploitation of a vulnerable adult. Six days later, police arrested three more people: Mary, Sager, and Mayfield. One month later, Cochran would beat McDaniel in a runoff. Three days after that, Mark Mayfield would be dead.

The week before he was arrested, Mark Mayfield couldn’t get comfortable. He would fidget in the pew at church and toss and turn in bed at night. On a family trip to the beach, he seemed unusually preoccupied; he kept referring to the possibility that he might need to suddenly return back home.

A compact, trim man with wire-frame glasses and blue eyes, Mayfield lived in a buttermilk-colored home with his wife, Robin. He had two adult sons, William and Owen. He was a committed Christian who took pride in his reputation; like most people, he wanted to be liked, and he was, by all accounts, conflict averse. When his sons were younger and his wife asked him to discipline them, “He’d take us out back and say, ‘I’m not going to spank you, but just don’t do it again,’ ” William says. For years, Mayfield did real-estate legal work at his father’s firm. Not long after his dad died, he set up a business arrangement with another lawyer who would handle his court work while Mayfield took care of the prep work behind the scenes. “Originally, I thought he was farming off the work,” says James Renfroe, the lawyer he partnered with. “But over the years, we became really good friends and I realized that Mark didn’t like to fight. He couldn’t do it.”

Before 2009, Mayfield had expressed little interest in politics, but seeing Rick Santelli’s CNBC rant calling for another Boston Tea Party stirred something in him. He started calling his friends who were active in GOP politics. About a dozen of them organized the state’s first tea-party rally in Jackson. That led to another rally on Tax Day, then a series of forums on the coming health-care law. Out of those early meetings came the state’s first tea-party chapter. Mayfield became its vice-chair. “He literally is the founder, the father, and the primary instigator of the Mississippi tea party,” says Roy Nicholson, another of the original members of the tea party.

At first, many of the state’s Republican officeholders were onboard. Congressman Gregg Harper spoke at the tea party’s Tax Day rally in 2009. Later, when tea-party groups expressed anger over Harper’s votes to increase government spending, Mayfield became the liaison for discussions between elected officials and the state tea party. “He was always trying to be the gateway to them,” says Nicholson. “He was the man they all trusted enough that he could have their private cell-phone numbers.”

In 2012, Mayfield was interviewed in the Mississippi GOP’s newsletter. He told the interviewer he’d been drawn to politics in the aftermath of the financial crisis and the bailouts, which inspired him to take action against the politicians he thought were creating dangerous levels of federal debt. “I have sensed a real urgency to preserve the nation that we love, especially after Americans were forced to accept what I believe are unconstitutional and financially unsustainable measures like the financial- and auto-industry bailouts, wasteful stimulus spending, the takeover of our health care through Obamacare, and an alarming increase in government spending and borrowing,” he was quoted as saying. He told his kids that he was getting off the couch and standing up for what he believed in.

On the Tuesday before Mayfield was arrested, as he and Robin lay in bed, she decided she’d had enough of his tossing and turning and demanded to know what was going on. “You know that Kelly guy who was arrested?” he told her. “Well, I’m involved in that somehow.” Mayfield explained that Mary had approached him about taking the photo. According to Robin, Mayfield said he wouldn’t do it but that he could set Kelly up with a friend — another attorney — who could help him out. When Mayfield went to the nursing home to clean out his mother’s room after her death, the attorney accompanied him. Mayfield showed him where Rose Cochran’s room was located, and the attorney then explained the location to Kelly over the phone, using a blocked number. (The attorney was never arrested or charged with any crime.)

Robin thought the photo-taking was a stupid, borderline-insane thing to do but not obviously criminal. When she heard the extent of her husband’s involvement, she was even more certain he’d be all right. She tried to reassure him that, at worst, the police might ask him to answer a few questions. Mayfield wasn’t convinced. “Robin, it’s politics,” he told her. “They’re going to come after me.”

Two days later, Mayfield was arrested at his office. At his arraignment that afternoon, he smiled wanly at the courtroom full of observers and reporters, as if embarrassed to be there. He was charged with a felony conspiracy to commit exploitation of a vulnerable adult. His bond was set at $250,000. Mayfield’s attorney, Merrida Coxwell, argued for a reduction. Mayfield was a well-known figure in the community, a father with no criminal record — he posed no flight risk. The request was denied. Coxwell looked at the judge in disbelief. “There weren’t any facts justifying this bond. It’s why I carry such a hard feeling in my heart,” says Coxwell. “Because I know they were fucking Mark over and using him as a pawn.”

For Coxwell as well as for some of Mayfield’s friends and family, the severity of the charges and the high bond felt more like retaliation than justice, punishment for supporting the insurgent who threatened to end Thad Cochran’s political career. They were suspicious that the Cochran campaign’s lawyers had reached out to Madison mayor Mary Hawkins Butler, a local political force in Mississippi and longtime Cochran supporter, rather than taking the matter directly to the police.

“You just have to do the math. If you have the GOP trying to sabotage McDaniel’s campaign and then you have Cochran people trying to sabotage McDaniel, and [Cochran supporters] are in charge of Madison city government, they decide who the Madison city judges are … people who have those kinds of jobs have to know what side their bread is buttered on,” says Tom Fortner, whose client, Sager, got a $500,000 bond on charges of conspiracy and tampering with evidence for his part in helping Mary do research on Cochran. “When bonds get set, that becomes obvious. You’re talking about a $500,000 bond set on a guy with no prior record of criminal history whatsoever and minor charges brought against him.”

Mayfield posted bond and was released later that day. Soon after his arrest, he told his wife that one of the banks he counted as a major client told him it was pulling its business. His name and mug shot were all over the press. Cochran’s spokesman, who’d been a longtime family friend of the Mayfields, referred to the “criminals” supporting McDaniel, a comment that particularly stung Mayfield. He became anxious and withdrawn. He no longer wanted to be seen in public and felt certain his reputation, and quite possibly his business, was ruined. At the office, “I just sit there and act like I’m busy,” he told his wife. He obsessed over the fate of his legal secretaries, how they would provide for themselves if his practice failed.

After Mayfield’s first court appearance, his son William hid his father’s guns in his backpack. A few days later, William noticed that one of them was missing. William and Robin demanded to see the gun. Mark told them it was for protection. “Protection from what? You’re not being hounded or threatened,” Robin told him. The three of them went upstairs to the attic, where Mark retrieved the gun he’d hidden in the insulation. William asked him to promise that he wouldn’t do anything crazy. His father agreed he wouldn’t. A grand jury was set to meet in June to decide whether to indict him. “I can’t go to jail,” he kept telling his family and attorneys. They assured him that he wouldn’t. But he kept repeating it, until it became a mantra: “I can’t go to jail.”

On the Saturday morning after Kelly’s arrest, when a reporter from The Hill approached McDaniel at a craft fair where he was campaigning and asked about the video, the candidate seemed to have never heard of it. “I don’t guess I’ve been awake long enough to see what’s happened,” he said. After the Hill story, Cochran’s aides released a voice-mail left by McDaniel’s campaign manager, Melanie Sojourner, for Cochran’s campaign manager, Kirk Sims. In the voice-mail, which was left earlier that morning, Sojourner said she’d learned about the arrest on Friday night and that McDaniel “is very upset about it and needs to have a personal phone call certainly with you, but he really wanted to have one with Senator Cochran if you think that would be at all possible.” McDaniel conceded that he’d been told of the arrest early Saturday morning, but he and his team stressed that they didn’t know anything about the plot. “I’ve never laid eyes on the video, but what I was sure of is that that was not anything that our campaign was going to be about,” he told a talk-radio show that week.

If the race was threatening to turn nasty before the arrests, now it descended into chaos: Cochran’s backers held that McDaniel knew more than he was letting on about the plot to take advantage of a vulnerable woman, and McDaniel’s contended that Cochran’s camp was exploiting the actions of a few rogue individuals to smear him. In a TV ad by Cochran’s campaign invoking the nursing-home incident, a faceless narrator said, “It’s the worst: Chris McDaniel’s supporter charged with a felony for posting video of Senator Thad Cochran’s wife in a nursing home? Had enough?”

McDaniel responded with his own ad decrying the “outrageous” character attacks. “When I announced my candidacy for the U.S. Senate, I told my supporters that I respected you as a man of honor as well as your longtime service to our state,” McDaniel wrote in an open letter published in the Clarion-Ledger. “Sadly, the actions your campaign has recently taken have forced me to reconsider my position.”

In the June 3 primary, McDaniel beat Cochran in a three-way race by 1,400 votes. The morning after the election, three McDaniel supporters were found locked inside the Hinds County courthouse, raising suspicions among bloggers covering the race that they were trying to steal the election.

Since McDaniel failed to carry a majority, the candidates were forced into a runoff. Mississippi law allows registered Democrats to cross over and vote in Republican races so long as they didn’t vote in their own party primary. During the runoff, Cochran’s campaign began featuring ads of black supporters and highlighting his record serving his African-American constituents, which included channeling funding to the state’s historically black colleges. A pro-Cochran super-PAC paid African-Americans to help get out the vote, and a flyer circulated in black precincts that said, “The Tea Party intends to prevent blacks from voting on Tuesday.” McDaniel accused Cochran’s campaign of pandering to black voters.

On June 24, Cochran beat McDaniel by 7,600 votes. Three days later, Robin Mayfield woke up to an empty bed. Looking over at her husband’s nightstand, she could see his phone and reading glasses still sitting there beside the bed. It struck her as odd — he wouldn’t have left for work without them. She got up and walked through the house. In the kitchen, his favorite cereal bowl, a chipped porcelain piece that used to belong to his grandmother, was sitting next to the sink. She walked down the quiet hallway leading to the garage, calling his name. “I felt this dark veil; it just fell over me,” she said later. “And I just felt so strange.”

She opened the garage door halfway. It was raining outside, and their two cats were sleeping on the roof of her husband’s car. Light was coming from under the closed storage-room door. She walked toward it and opened it. Her husband was lying on the ground, facing her, surrounded by garden equipment and folding tables, with a revolver in his hand. Robin called 911. When the ambulance arrived, she collapsed in the rain and pulled herself into a fetal position.

The tributes poured in: from the governor and members of Congress, state and local officials. McDaniel issued a press release calling Mayfield “one of the most polite and humble men I’ve ever met in politics.” Robin couldn’t bear to hear any of it. “All of those officials who were behind Cochran, Mark had helped many times over the years,” she said. But after he was arrested, she felt they abandoned her husband. “They tucked their tails and ran.” In his briefcase she found a list of people who had reached out to him after his arrest. “Those officials? He didn’t hear from them at all.” McDaniel and other politicians sent Robin plants as a condolence gift. She couldn’t stand having them in the house, so she put them in the garage. “I just watched them wilt,” she says. “It reminded me of how Mark’s life was from the time he was arrested to the time he died.”

Tea-party activists were also fuming over Mayfield’s death. A right-wing blogger named Charles C. Johnson, known for his outlandish claims online, tweeted that Republican operatives had caused Mayfield’s suicide. Others were shocked as well.

“I’ve represented a lot of people for acts so heinous I won’t even discuss them,” says attorney Doug Lee, who represented Mary. “When I saw the reaction of law enforcement and the political Establishment to what these people did, I was simply amazed. I still have a hard time reconciling that, and it makes me very angry. It didn’t seem that anybody could be guilty of anything, except Clayton Kelly was arguably guilty of a trespass. The others are arguably guilty of conspiracy to commit a trespass. To tell the truth, I don’t know that you can be guilty of a conspiracy to commit a trespass.” (Several officials involved in the case, including Hawkins Butler, the district attorney, and McDaniel, either declined to comment or didn’t respond to repeated interview requests. Through lawyers at Butler Snow, Cochran’s campaign also declined to comment on the record.)

After the race, McDaniel refused to concede, claiming Cochran’s attempt to win African-American Democrats was evidence of voter fraud. “We are not prone to surrender,” McDaniel said in his Election Night speech. Soon after, Johnson published an explosive scoop: A self-described African-American reverend named Stevie Fielder said he was given money by the Cochran campaign to bribe black voters into going to the polls for the senator. McDaniel offered a $1,000 reward to anyone who could provide evidence that the senator’s campaign had broken the law. Later, Fielder said that his comments had been “hypothetical” and selectively edited. Johnson admitted to paying Fielder for the story. McDaniel continued to fight the outcome in court, but by August his options were running out.

This month, Clayton Kelly pleaded guilty to a charge of conspiracy to commit burglary. The district attorney prosecuting the case agreed to drop his burglary charges, for which he could have faced up to 50 years in prison. Kelly was sentenced by a judge to two and a half years in prison Monday, followed by two and a half years of probation. Before the verdict, Kelly’s attorney Camp told me he planned to argue that there was no burglary — Kelly was let into the building by a security guard and was acting in his capacity as a journalist trying to get a newsworthy story out. “It’s going to be very difficult to prove that a crime was committed,” Camp said. Kelly ultimately took the plea because he didn’t want to risk spending decades in jail.

John Mary agreed to serve five years on probation, after which his record will be cleared. Sager, the researcher, will have his record cleared after three years’ probation. All three have been quiet online since the arrests: Constitutional Clayton’s blog hasn’t been updated since May of last year, Sager’s Twitter feed was deleted, and Mary’s has been empty except for a few retweets. Three months after their initial arrests, the lead police investigator on the case was reassigned to animal control.

“Is it a conspiracy or just political maneuvering? What’s the difference?” says Lee, Mary’s attorney. “What the Cochran side did, you can call that a conspiracy and other people will say it’s politics as usual. It’s wrong either way. Dead wrong. A lot of this stuff that looks like conspiracy is just dumb redneck crap.”

Earlier this year, McDaniel and his allies launched a PAC with the stated mission of challenging Republican Establishment candidates. The Senate Conservatives Fund, another tea-party PAC, started by Jim DeMint, launched a campaign called Remember Mississippi, urging supporters not to forget the efforts of the national GOP to crush McDaniel in the Senate race. The PAC asks supporters to join in a boycott of the National Republican Senatorial Committee. It makes no mention of Mayfield or the others. The website has 20,000 pledges listed so far. McDaniel is rumored to be eyeing a bid for Congress against another incumbent Republican, Representative Steven Palazzo, next year.

Rose Cochran died in December. Thad Cochran married his assistant, Kay Webber, in a private ceremony in May.

*This article appears in the June 15, 2015 issue of New York Magazine. It includes information on developments in the story that occurred after press time.