Tuesday morning felt normal to Monica Foy, a junior and English major at Sam Houston State University. The first thing the 26-year-old, who lives outside Houston with her husband, did when she woke up was check her Twitter and Facebook feeds. Both were full of people mourning the loss of Darren Goforth, a Harris County Sheriff’s deputy who was murdered Friday night by a man named Shannon J. Miles, who came up behind him at a gas station, shot him in the back of the head, and then emptied every bullet in his gun into the officer. (No one has identified a motive, but the Houston Chronicle reported that Miles has a history of psychiatric illness.)

Foy felt terrible about the shooting, she explained to Daily Intelligencer in the first full interview she has granted after a terrifying few days, but as a politically active person who had been watching with interest and sympathy as the Black Lives Matter movement has grown, she was also bothered by what she saw as a double standard on display in the aftermath of Goforth’s death: When an unarmed person of color is killed by police, she said, there’s often an immediate effort to prove that they were “no angel,” that in some way or another they had it coming (though George Zimmerman was a neighborhood watch volunteer rather than a police officer, this general tendency toward victim-blaming tendency was pretty clearly on display in the case of Trayvon Martin). When a white person — especially a police officer — is killed, people seem much more able to accept the fact that some killings are simply unjustified, full-stop.

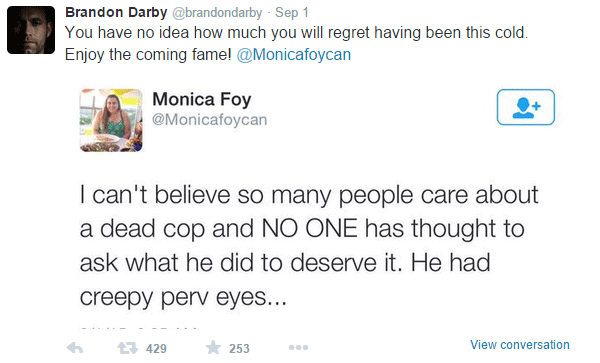

So Foy tweeted a dry joke about what she saw as the different ways society responds to different deaths: “I can’t believe so many people care about a dead cop and NO ONE has thought to ask what he did to deserve it. He had creepy perv eyes …”

Viewed after the fact, this was clearly an inopportune context in which to make this point — not to mention an insensitive and offensive way to make it. But to Foy, it was an observation she was making privately — she had maybe 20 Twitter followers at the time, and about half of those were family. “I never would write anything like that on Facebook, which is why I have a Twitter account,” she said. “I wrote it there because I knew that no one would see it. That’s something that I knew that morning. There was no hashtag, I did not mention the deputy by name, I did not say Houston, I did not say anything specific at all.”

Disastrously for Foy, the tweet quickly got screen-grabbed and began spreading among right-wing Twitter users, who immediately sought to amplify it. It found its way to Brandon Darby, managing director of Breitbart Texas, part of the far-right Breitbart website. Darby, as he would soon explain, quickly decided that it was on him to step in and defend the murdered deputy’s legacy against the threat apparently posed to it by a college student’s tweet. And as a journalist with a good-size megaphone, there was one obvious way to do that.

Darby directly informed Foy what was in store for her:

Foy didn’t understand who Darby was or the sort of platform he had. “I was like, Yeah, right — good luck,” she said. “I just didn’t take it seriously.” Meanwhile, the first round of Twitter harassment started in earnest during her drive to school with her husband as various right-wing users caught wind of her tweet and came after her for it. “I started reading some of the comments out loud to my husband, and we laughed about it,” Foy said. “We didn’t think anything of it — we just thought it was going to be an isolated thing where people say dumb stuff, and that would be it.” But when she arrived at school at around 8:30 a.m., she checked her phone again and saw that her mentions “had just exploded.” That was when she decided to take the tweet down, and when she noticed that it was being posted to a number of right-wing websites.

Things were about to get much worse. Darby followed through on his threat, publishing a brief article on Breitbart about Foy’s tweet, describing her as a “Houston area #BlackLivesMatter supporter” — a reference to the fact that a half-hour before her tweet about the murder, she had published another one consisting solely of the hashtag. The Breitbart writer linked directly to Foy’s Facebook and Twitter profiles and mentioned that she was a Sam Houston State University student. “Foy deleted the tweet after numerous individuals began criticizing her on the social media platform,” Darby noted. (I emailed Darby some questions about why he saw Foy as a legitimate target, and I got back a response from a Breitbart spokesperson who said that Darby’s article was part of the website’s ongoing effort to investigate the “violent” nature of BLM and its followers. The response is hard to take seriously given that Foy couldn’t be further from a public BLM figure, and that Darby openly admitted to a more straightforward motive: He was furious about the tweet and wanted to bring Foy “fame” among Breitbart readers as retribution.)

For the initial phase of the explosion that followed, Foy was offline: The first round of Twitter notifications had drained her phone’s battery, and she had class anyway, so she kept it off from 10:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m., shortly after she got out of class. “For the most part, I just put it to the back of my head, because I was in class and that was my main concern,” she said.

But while Foy was in class, Darby got his wish: The story almost immediately went viral, leading to what can only be described as an epic and scary shitstorm. Her Facebook and Twitter feeds were inundated with threats and harassment. On the Breitbart website and Facebook page, the number of comments ballooned; there are now more than 41,000. A huge number of the tweets and comments ridiculed her physical appearance, and there was a racially aggrieved undercurrent to many of them: There was frequent speculation about Foy (who looks and identifies as white) sleeping with black men, as well as some comments hoping that she got raped by one.

When Foy got back online after class, she said, “That’s when I knew I was FUBAR.” She tried to figure out how to turn off notifications on her account or make it private altogether, but couldn’t. So the notifications kept coming in, a “constant vibration” as she drove from school to her husband’s office to figure out what to do. “It was kind of surreal,” she explained, “and I was kind of displaced from the situation, almost. I felt like an outside party watching it happen, I didn’t really feel hurt by the comments because it just felt like they’re ghosts — it wasn’t people that I know, that I’m friends with, or that I see in my community or care about their opinion of me.” The individual abusive comments didn’t bother her, she said, but rather the galloping speed at which new tweets were arriving, and the sense that she had no way to make them stop.

***

A fundamental principle of online-shaming is that the process robs people of the context that makes them human beings. The whole point is to take a snapshot of someone at their most vulnerable, at their most clueless or seemingly callous, and broadcast that as far and wide as possible. As Jon Ronson explains in his book So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed, when you dig into the story of the target, there’s inevitably some bit of nuance that casts the offending remark in a different light.

In the case of Justine Sacco, who was victimized by a worldwide shaming mob after a tweet of hers went viral while she was on a plane to South Africa, it turned out that her remark about the difference in AIDS rates between white and black people was a lame attempt at edgy, South Park–ish humor. In the case of a pair of women who posted a Facebook photo of themselves flipping the bird at Arlington National Cemetery, leading to a right-wing mob similar to the one targeting Foy, it turned out that they had an inside joke of taking silly photos in front of signs — it didn’t even occur to them that they were insulting deceased veterans. This sort of context is vital to understanding that there’s usually a longer, more complicated story behind the remarks that spark these incidents than “The person who posted this is evil incarnate.”

Foy’s case echoes Sacco’s in certain ways — she was making a politically incorrect remark about a tragic subject (and was offline for a portion of the phase when the outrage first ramped up). But her broader fixation on the problem of victim-blaming stems from something that happened when she was a teenager. “I went to a really racially charged high school,” she said. Her junior year, a Mexican-American student in her class named David Ritcheson — “somewhere between an acquaintance and a friend, since we were also neighbors,” she said — was invited to a party by a girl, and was then viciously attacked. “Four or five skinheads — self-claimed skinheads — beat him unconscious, dragged his body outside, sodomized him, poured broken glass down his throat, and bleached his skin. He was in intensive care for the remainder of the school year. He came back our senior year and you could tell that while he was there — we voted him prom king, and he had a great girlfriend and supportive friends, and he was a football player and had people supporting him … he was still dead inside. He wasn’t the same person, obviously, after coming back from something like that. And the summer after we graduated, he jumped off a cruise ship and killed himself.” The attack gained such notoriety that it has its own Wikipedia page, and two teens were sentenced to lengthy prison terms for their role in the attack, which was sparked when the attackers heard that Ritcheson had tried to kiss a 12-year-old girl.

Foy was an Air Force Junior ROTC cadet at the time, and she says she “distinctly” remembers that “a lot of conservative people, military-raised and that sort of thing, wanted to blame” Ritcheson for the attack. “Because they’re like, Why was he there talking to a younger girl?” That stuck with Foy: Even in the case of an unspeakable, torture-fueled hate crime, there were people rushing to say the victim had brought it upon himself. “I was ostracized for defending him and saying it was sick that anybody would blame the victim, and I distinctly remember my colonel telling me, Why do you care? Is that your drug dealer or something? And I just feel like I’ve always been on the outside, but I stand by the victims.”

None of that means that it was wise for Foy to have made an ironic point about victim-blaming directed toward a police officer who had been tragically murdered just days before, or that people who were offended by it were wrong to be offended. But it helps explain why she posted what she posted. This context, of course, was invisible to the online hordes who by mid-afternoon were not only sending nasty comments to Foy, but also barraging her with death threats.

***

By the time Foy got to her husband’s office, she’d received a number of increasingly urgent texts from friends who were worried about her — they’d seen what was going on online, and, not knowing Foy had had her phone off for five hours, had noticed that she wasn’t responding. Her phone number and address had been leaked online multiple times, and the death threats had started coming in via Twitter, phone calls, and text messages. Foy and her husband rushed home, grabbed what they could — “I was looking out the window the entire time that we were there” — and headed for Foy’s mother’s house.

Foy said she received about 30 voice-mail death threats. Here are some of them — the language is obviously not safe for work.

Foy and her husband got to her mom’s house about 30 minutes before her mom got home. When she did, they tried to explain to her what had happened, but it went about as well as one might expect, stereotypically, when a millennial tries to explain social media and internet-shaming to a parent. The conversation only lasted about ten minutes. “That’s when the cops showed up,” said Foy. Apparently, one of the online crusaders attacking Foy had discovered she had an outstanding warrant for a misdemeanor assault charge in 2011, and had tipped off law enforcement (though it’s also possible the police themselves had run her name — Foy said people on Twitter told her they were going to forward the offending tweet to law enforcement). The police were there to arrest her.

“The cops didn’t mention” her tweet, Foy said. “The arresting officer was the most polite person in the world — like, he had grandmother qualities about him. So gentle. When we were in the car, I was in the backseat, and I was like, Officers, I just want to take the opportunity to tell you how twisted my words got, and how much I support you, and I would never condone killing an officer or another person, ever … They took it very well, they were really welcoming to the apology, and they were just completely professional about it. They weren’t passive-aggressive or anything.”

As Foy was standing at the counter at the jail, getting booked, she said she heard an officer, busy with other tasks, take a phone call on speakerphone. At the other end of the line was the voice of a man she recognized from an earlier voice-mail. First, he asked to speak to an officer who apparently didn’t exist, then he asked, “Was that Twitter chick arrested yet?” The officer quickly picked up the phone and took it into another room. “So obviously the [officers] knew about the tweet, but they just played it off really cool when they were with me,” said Foy.

A couple hours later, Foy was bailed out, but by then her mom’s address had also been posted online (Foy said she also heard of Facebook plans to organize a protest at her mom’s place), so she and her husband had to move to a second safe house.

***

The abuse extended to anyone with a visible connection to Foy. Foy’s sister, a law student, reported to her that the dean of her law school had gotten angry emails and voice-mails.

So it’s no surprise that Foy’s university, Sam Houston State, which is known for its criminal-justice program, itself became a target.

The university’s initial response didn’t necessarily help matters. It issued two statements: The first, by Steven Keating, assistant director of marketing and communication, explained that Foy’s tweet would be “evaluated” to see if she had violated the school’s Code of Conduct. The next day, the university’s president, Dana Gibson, issued a lengthier statement of her own in which she reaffirmed the university’s support for law enforcement. At a time when it was plainly obvious to anyone who was watching that yes, Foy had said something very offensive, but that she was also being inundated with hate and death threats by an online mob, Keating wrote that the university “appreciates the enormous public response in support of law enforcement,” while Gibson wrote: “It’s reassuring to see how much pride emerges when the Sam Houston name is called into question, and I am heartened to see so many people stand up for law enforcement.” (Neither an email to the university’s communications shop nor a voice-mail left with Keating were returned.)

Foy said she feels like the university very much has her back, though, based on her offline communications with administrators. “I know that they were extremely pressured to make a statement, and that statement was saying that they would investigate the tweet and they didn’t condone violence at all. And I just felt like if I were the university, I would have said that, too.” She said that the dean of student life has confirmed to her that the university isn’t going to look into disciplinary action. “I’ve actually gotten an outpouring of support, saying anything I needed from them — they’ve given me several different numbers, several different outlets. In their eyes, as a student, I’m exonerated.” She plans to return to school on Tuesday, and while she says she “might feel a little worried” when she walks by the school’s criminal-justice building, overall she has a good support network in place. She said professors have reached out to her and have helped her develop safety plans in the event anything happens on campus. Multiple people have offered to escort her from class to class, in fact, and have given her their personal cell-phone numbers in case she ever feels unsafe and needs someone to talk to. (Thursday, Foy issued an apology via a statement she sent to the Chronicle.)

The bigger threat probably comes from beyond SHSU, though, and it stems from the difference between run-of-the mill anger about a stranger’s behavior, which dissipates relatively quickly, and obsession, which lingers. “A lot of people are angry, and they have a right to be, because, you know, a guy was pumping gas in his uniform and he got shot 15 times in the back of the head, and that’s fucked-up,” said Foy. The problem is that she appears to have picked up some rather dedicated harassers and stalkers, like the guy who both called her at home and called the police. “I don’t know what they don’t have going on in their lives that they have so much time to do that, but that’s what they fill their time with.” Whatever motivates them, Foy said she takes their threats very seriously. “You can tell a person’s affect from the way they speak, and you can tell they’re just not stable.”

Thursday, for the first time since the tweet, Foy didn’t get a single death threat. But she said she woke up Friday to two new voice-mails again threatening her life. “I don’t think I’ll ever feel safe again,” Foy said, simply because a small percentage of the people who attacked her seem so unhinged. “To the majority of the public it’ll blow over. Labor Day weekend’s coming up, and I know people are going to party and forget. But there is a percentage of people that — I’m on their list. I’m on their eternal list, and they want my head on the chopping block.” It’s a numbers thing, in other words. “It just takes one bullet to kill me from one gun from one person, and that one person is out there. So no, I will never feel safe. Not for me, not for my family, not for anyone I know who has publicly supported me.”

(Update: This article originally implied that George Zimmerman was a police officer rather than a neighborhood watch volunteer. The language has been updated to accurately describe his position at the time of Trayvon Martin’s death.)