Lo! Yet another mucky wave of 1970s New York nostalgia is quick approaching, ready to dump its scummy self upon our stolidly sleek shores. The next few months will see the advent of Baz Luhrmann’s Empire prequel detailing the birth of hip-hop, along with the release of Garth Risk Hallberg’s 1,000-page, ‘70s-inspired novel, City on Fire. These celebrations of sleazological cool are cyclical, like the coming of winter and the banging of the pipes in my old apartment on St. Marks Place. Maybe it is perverse to yearn for the days when Daniel Rakowitz chopped up his Swiss girlfriend and made her into a stew that, like a demented Florence Nightingale, he fed to the homeless people camped out in Tompkins Square Park. But it makes for a better read than a half-dozen food blogs. The mean-street memory of the 1970s adheres to the collective big-city conscious like Proustian poo wedged in the waffle soles of your Chuck Taylors when they were still $19 at Vim’s; you didn’t even actually have to be present to be haunted by the time. And yet the nostalgists, even those of us who lived through it, have a habit of getting the decade wrong.

The ‘70s are a Jekyll-and-Hyde of New York eras. On one hand we fear the terrors of the time, the junkies on the fire escape scheming to steal a $50 rabbit-ear TV, the return of jazz fusion. After the 2008 crash there were cries that the Bad Old Days were coming around again, as if the malfeasance of Wall Street ganefs would instantly cause armies of crum bums selling counterfeit Tuinals and Valiums — “Ts and Vs” was the hawker cry — to rise from the manicured shrubbery of Union Square Park. The onset of De Blasio Time has rewound the harbinger chorus. As the bullets fly in Staten Island, the mayor stays in his Park Slope gym squat-thrusting, the tabs scream. It is only a matter of time before Manhattan again falls off the edge of the earth at 96th Street (for white people, anyway) and Gerald Ford tells the city to drop dead.

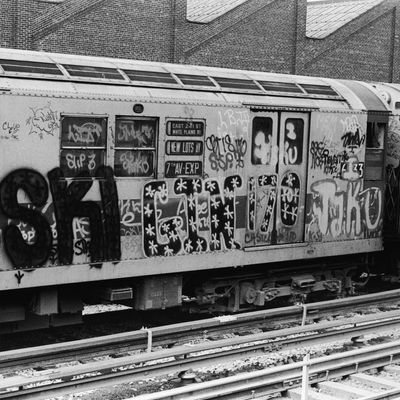

On the other hand, few times in recent New York history have been so longed for, so endlessly discussed. (“Blah Blah Blah New York in the Seventies” went a recent headline on the Awl.) The building of the Brooklyn Bridge, the bright lights of Broadway, Bird and Monk on 52nd Street — how could any of that dry-bone history hold a candle to the moment Afrika Bambaataa started those turntables spinning in the schoolyards of the burning Bronx? Was genius ever so accessible as when Dee Dee Ramone vomited on your pant leg on the Bowery sidewalk in front of CBGB? Sure, you could get killed on the LL, the EE, the RR, or some other mystery train, but at least the last thing you’d see would be a museum-quality Futura 2000 full-car graffiti, so where’s the bitch in that? The 1970s! That was New York when it was real, when rents were cheap, the cabbies were white, and you didn’t really have to know how to play to be a star, or so the plotline goes.

Back in that particular day, punk friends made fun of hippies, hair down to their butts well into their 20s. That wouldn’t happen to them, the next generation of cool kids declared. Raised on ten hours of TV a day, they were hard-bitten realists from the “live fast, die young, leave a beautiful corpse” school; they would not live long enough to engage in phony nostalgia for the scruffiness of their youth. Yet here they are, nearly 40 years later, still in their leather jackets and pointy little boots, no different than doo-wop singers stuffed into iridescent jumpsuits doing that one number that makes everyone remember who they once were.

A few weeks ago the Times ran a feature that rounded up a fair smattering of the official ‘70s suspects — Philip Glass, Lucas Samaras, David Johansen, DJ Kool Herc, Fran Lebowitz, etc. — for a waxworks group shot. “They Made New York” was the headline. Guess Nicky Barnes, David Berkowitz, Meade Esposito, and the rest canceled at the last moment. The piece ran in the fashion supplement T, which was more on the money. “Blank Generation” is a great song, but even back in 1975 the general consensus was Richard Hell’s nom de icon was a tad on the nose.

This is not to say that no one who didn’t spear a rat with the business end of a police lock pole can really claim to have experienced New York in the 1970s. But the standard history leaves out a lot. The underground disco movement during the early part of the decade, vast hidden parties in the wasteland sections of town where blacks, whites, gays, and straights came together to dance to the magical segues of David Mancuso, Nicky Siano, Larry Levan, and the rest, is consistently written out of ‘70s mythmaking (though the moneyed glamour of Studio 54 makes it in). In retrospect, that sort of hothouse integrationism didn’t have a chance in hell against the steamrolling macho identity politics of the “disco sucks” white punkers, the hardening edge of rap, or wholly necessary feminism.

Everyone chooses to remember what they want to remember. At this stage, however, attempts to crush New York in the 1970s into a few however-heroic art and politic tropes pretty much boils down to reductionist product-mongering. The picture is far bigger than that. The fact is what usually falls under the rubric of New York–in-the-1970s was really a multi-decade project that began in earnest during the 1964 Harlem riots, which put white flight into high gear. The period lasted until the Crown Heights riots in 1991, which led to the election of Rudolph Giuliani in 1993. In Roman centurion mode, Caesar Rudy sent his cop legions to vanquish the dark-hued Visigoths and reclaim territory for the throne. His success set the stage for the Bloomberg imperium, during which the magic of capital would extend the investment-safe realm to deep Brooklyn and even uncharted Queens, thereby creating the New York we find ourselves living in today.

Change is the genius of the city, what has always made New York what it is. But the whiplash rezoning of more than 40 percent of the five boroughs during Bloomberg’s tenure has produced a generational-based moral crisis. Longtime residents no longer feel the joy of the ever-altering landscape, the rapid clip of cosmopolitan turnover that creates continuity. They walk about gaslighted, as if suddenly set down in a drug dealer’s apartment, with everything new and shiny, bought at the same time.

I remember one time, back in the late 1970s, when I went to interview Carl Weisbrod, now chairman of the New York City Planning Commission and a key player in every mayoral administration back to John Lindsay. At the time Weisbrod was head of a committee to revamp Times Square, which, with its array of porn stores and sticky-floored movie houses, could rightly be called the capital of the New York 1970s. Weisbrod had an office in the Art Deco McGraw-Hill Building, then the tallest (and newest) in the area. As we stood looking out the 30th-story window, Weisbrod told me that no new structure had been built west of Sixth Avenue in decades. In the city of skyscrapers this was a shocking fact. “We will change that,” the future head of the Planning Commission told me. In 1979, for anyone walking past the Port Authority Bus Station it was impossible to imagine the extent to which Weisbrod would be right about that, and how fast it would happen once it began.

In this, I am far from blameless. I’m not pulling rank when I say I lived on St. Marks Place from 1974 to 1992 (roughly the entire ‘70s) in a fifth-floor walk-up with no sink in the bathroom, which works out to 19 years of teeth-brushing in the kitchen sink. What could you expect for $168 a month? When it was time to go, we went. Someone else could brush their teeth in the kitchen sink. I had no idea the house I bought in Park Slope would increase in value several times over in the two and half decades I have owned it. It is one more double-edged sword; as our real-estate values go up, the neighborhood gets duller in direct proportion.

Therein lies the problem, the dilemma of the accidental gentry. It was comforting to know that my 5-year-old daughter would likely never again find a loaded .38 pistol in the bushes at Tompkins Square like she did while attending day care at Tenth Street Tots. By moving out of the neighborhood we were following a time-honored immigrant path, under the impression we were doing the right thing for our family. Now that same daughter, in her late 20s, resides in Chicago. She can’t afford to live a normal life in the city of her birth. My son moved to Denver for many of the same reasons. They like these places, the lake, the mountains, the legal pot, but they miss the city like we miss them.

My kids are far from alone in this situation, of course. All the time you hear that same old saw — that New York is dead, that the last good times have been sucked out of the place by people like me. Me, Donald Trump, and who knows how many globalist rich people willing to plunk down $90 million for a pad they will never live in.

It is said that in times of discontent, a society yearns for the last era of perceived sanity. ISIS desires the seventh century; New Yorkers dream of the ‘70s. My heart goes out to those who think they missed the last good time to be young in the place of their dreams. It is hard to begrudge longing for rent stabilization. But what are you going to do? If you want to see the Talking Heads at CBGB with four people in the audience (rather than at some suburban shed like you did) or get your car broken into while attending a Cold Crush show at Harlem World in 1981, that ship has sailed. Maybe Baz Luhrmann will successfully channel those evenings for the born-too-late, just as Clint Eastwood once got Forest Whitaker to impersonate Charlie Parker for those of us who missed sitting at the bar at the Three Deuces. But I doubt it. During the real 1970s the dumbest thing any would-be cool kid could do was sit around Kettle of Fish hoping some long-toothed beatnik like Kerouac and William Burroughs would stumble through the door to be venerated. No matter what it says in the New York Times, the chances of you imbibing the egalitarian synergy of high and low culture with Jean-Michel Basquiat at the Mudd Club were pretty slim to begin with. Plus, believe me, you didn’t really want to be walking down Pitt Street when that guy took the knife off his belt.

This doesn’t mean all is lost, that the current-era would-be New Yorker is consigned to a life of 12 hours of nonunion work in a cubicle and cramming into a $2,700 three-bedroom in a shit section of Bushwick with the M train right outside the window. There’s plenty of New York out there, even if someone doesn’t give you a $2 million advance to write City on Fire. The city is actually more interesting than ever out at the margins.

The other day I was in an old Italian social club on Stillwell Avenue waiting for my front end to be aligned by Louie at Hilna Tires. A woman from Tbilisi, Georgia, was instructing another employee, a lady from Tajikistan, how to make steamed milk the way the octogenarian Sicilians in the place like it. A Caribbean character in a rimmed-out Jeep was stopped in front, blasting some unknown dance-hall tune. The old guys covered their ears, but the women liked it and started dancing. When the light changed everything returned to normal. The people in the coffee shop, alerted to the scenario, shrugged. It was New York in 2015, nothing more or less. If you like that sort of thing, there’s plenty of it still around.