How One Man’s Face Became Another Man’s Face

A story about cutting-edge medicine and the mysteries of identity.

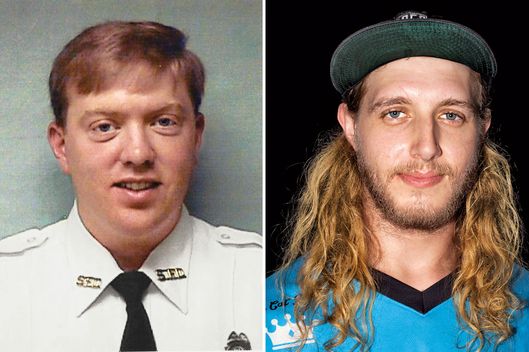

For the moment, the face belongs to no one. It floats in a bowl of icy, hemodynamic preserving solution, paused midway on its journey from one operating room to another, from a 26-year-old Brooklyn bike mechanic who’d been declared brain-dead 48 hours earlier to a 41-year-old Mississippi fireman whose face had burned off in a blaze 14 years ago. The mechanic’s face, though nearly flat, still bears a few reminders of its former owner: a stubble of dark-blond hair, pierced ears, a hook-shaped scar at the spot where surgeons had entered his skull trying to save his life. A surgeon reaches his gloved hands into the blood-tinged liquid and kneads the face, draining the last of the mechanic’s blood. Then he lifts the face up to a camera, showing off his handiwork. As he raises it, it seems to inflate and take the shape of a face again, one that no longer resembles the cyclist. The forehead is shorter, the cheeks puffier. The lips have fallen into a crescent, as if smiling. The face looks like it will when, an hour later, it is fitted over the raw skull of the fireman waiting in the next room.

Patrick Hardison

September 5, 2001 was a beautiful late-summer day in Senatobia, a town of 1,497 families in northwest Mississippi, not far from the Tennessee border. Business at Senatobia Tire off Main Street was slow, and when owner Patrick Hardison had seen the Senatobia Fire Department dispatcher at lunch, he had needled him, half in jest: “Get us a call.” Hardison, 27 at the time and a volunteer for seven years, had known most of the 30 other volunteers since they were schoolkids; they’d hunted and fished together, then in their 20s signed up to fight fires together.

The two-tone alarm emitted by the pager on Hardison’s belt sounded at about 1 p.m. Speeding up Main Street in his Chevy pickup, Hardison could get to the firehouse in just a few minutes. Only the first arrivals got seats on the truck, and a seat meant you’d fight the fire. “You wanted to be the one telling the story, not listening to the fun other guys had,” Hardison said. That day, Hardison pulled up just in time, beating out his former brother-in-law for one of the spots. When the volunteers arrived at the mobile home 15 miles away, flames were shooting through the roof. “The worst fire I’ve ever seen,” said Bricky Cole, one of the volunteers that day and the husband of Hardison’s cousin.

Both of the family’s cars were parked outside the mobile home, and a man was in the yard screaming, insisting his wife was still inside. Hardison and three other firefighters entered the house, turned into a living-room area, then into what looked like a den. The ceiling was already collapsing in sections; not seeing anyone, Hardison backed out of the door. Then he spotted a window and climbed through it back into the burning structure.

A few minutes later, Hardison’s chief screamed for his people to get out. Hardison was retreating when the ceiling collapsed on his head and shoulders. He fell to his knees. He could feel his mask melting and wrestled it off. He held his breath and closed his eyes, which spared his lungs and preserved his vision. Somehow he made his way back to the window. A fireman pulled him out.

Hardison’s face was on fire. Another fireman doused the flames with water. Cole held him as the paramedics slid an IV line into his arm, though Cole didn’t know who the burned man was. “His face was smoking and flesh was melting off,” Cole recalled. “It was all char.” At about that time, the woman who they thought was trapped in the house walked up the road. She’d been fishing at a nearby stream.

David Rodebaugh

In September 2001, David Rodebaugh was 12 years old and living in Columbus, Ohio, where he was on his way to becoming an accomplished skateboarder, snowboarder, and BMX biker. He could do backward somersaults in the air and 360-degree helicopters, swinging his bike in a complete circle. Rodebaugh bounced around as a kid. Later, his mother, father, and both grandmothers would all claim to have done the lion’s share of raising him. Rodebaugh couldn’t sit still for school, but there was little he couldn’t do with his hands. At 20, he announced he wanted to move to New York. Neither his mother, Nancy Millar, nor his father, Gregg Rodebaugh, believed in reining him in. “I never put a leash on him,” recalled Millar. “Just call me before the ambulance does, that’s all.”

In 2009, Rodebaugh landed in Brooklyn among the hard-core bike-messenger community. “We live by the bike. We ride hard as fuck. We own the streets. We are the streets,” said Al Lopez, whose one-man messenger company is called Cannonball Couriers. Lopez took to Rodebaugh immediately: “He was down. He was fun. He was smart. He was a bro.” Lopez got to know him through the Lock Foot Posi, an insular gang of a dozen or so cyclists (“Lock Foot” refers to the way to brake on a gearless bike). “We’re like from the land of the misfit toys,” said Lopez. “Rejected from a larger mass but united through a kind of personal dysfunction. We’re our own family. Dave fit right in with us."

Eduardo Rodriguez

In September 2001, Dr. Eduardo Rodriguez, then 34, was in his ninth year of medical training. The son of Cuban immigrants, he grew up in Miami and held the ambitions of many first-generation Americans. “I wanted to make money, raise a family, be a professional.” So he set out to become a dentist. In 1994, he was doing a residency in oral and maxillofacial surgery at Montefiore hospital in the Bronx, when Dr. Arthur Adamo, director of the program, took him aside and told him he was impressed with his surgical skills. “You’re better than most people at this; you’re better than me,” Adamo said. It was the moment Rodriguez’s ambitions started to become grander. He studied surgery at Johns Hopkins and microsurgery in Taiwan. He finished his 16 years of training at age 37, an elite plastic surgeon with a specialty in reconstructive surgery.

Rodriguez was introduced to the possibility of face transplants in 2003. At a medical conference, a surgeon showed photos of a brown rat with a white face and a white rat with a brown face. She’d transferred one to the other. It seemed little more than a surgical stunt, but the next year, two French doctors transplanted part of a face onto a 38-year-old woman who’d been mauled by a dog. Nine years later in the medical journal The Lancet, Rodriguez and co-authors reviewed the 28 face transplants that had been performed in the world. Most were partial — the French woman received a nose, cheeks, lips, and a chin. Rodriguez thought the field was ready to take bolder steps. “From a moral standpoint, if we were going to push patients to the possibility of death, the reward has to be great. Why risk it with a mediocre result?” The Department of Defense, hoping to help wounded soldiers, expressed an interest in funding his work. But it wanted proof of concept. To satisfy the DOD, Rodriguez transplanted a face from one live monkey onto another. Then, in 2012, at the University of Maryland, Rodriguez performed his first human transplant, on a man whose face had been shot off. It was the first surgery to replace, in addition to the face, the jaws, teeth, and tongue.

In 2013, Rodriguez became the chair of plastic surgery at NYU’s Langone Medical Center and began to assemble a team to perform facial transplants — surgeries which can cost, including pre- and post-operative care, nearly $1 million. He and his surgeons spent hours practicing removing faces from 14 cadavers. “We had to be able to do this thing in our sleep,” he said.

Rodriguez is a lean, imposing six-foot-three. He never raises his voice, no matter the subject, and he brims with confidence, some would say arrogance. “When I put my mind to something, it’s going to happen,” he told me. A year into his tenure at NYU, Rodriguez felt his team was ready to attempt another transplant—this one more extensive than any performed before. He even had a patient in mind. He had first met Hardison in 2012, when he was on the faculty at Maryland, and he immediately understood the opportunity the former firefighter presented. “Patrick was the ideal patient,” he recalled. Now all they needed was a face.

Hardison

In photos taken before the fire, Hardison has a pleasant, unassertive face, with round cheeks, blue eyes, and blond hair curling over his forehead. His face was a backdrop to his patter, which was friendly and constant. It’s part of what made him a good salesman. “People came for tires and walked out with wheels,” said Bill Weeks, his friend and fellow firefighter. Some days, he netted $10,000. “Money in your pocket,” Hardison said. At 26, he purchased his dream home, a four-bedroom on 20 acres “with a shop and an inground pool and a two-story playhouse.” He and his second wife, Chrissi, had three kids at the time, one each from previous relationships and another together. “I planned to retire at 40,” he said.

Sixty-three days after the fire, Hardison returned home from the regional medical center in Memphis wrapped in gauze, his eyes sewn shut. “He came home mummied,” said Chrissi. “He wouldn’t look in the mirror for a long time.” Just two years into their marriage, Chrissi became his nurse, feeding him, bathing him. “He was depressed and angry at the world, understandably,” she said. Sometimes he’d wander off into the acres around their house and Chrissi would call his firefighter buddies to track him down.

Hardison had 71 surgeries over a dozen years. Doctors took flesh from his thighs and pulled it over his skull. “Gradually, his head began to look like a head,” said Chrissi. A surgeon implanted magnetized pegs — osteointegrated implants — in the sides of his head to which prosthetic ears could be attached. Eventually, surgeons turned his lips inside out to give him the semblance of a mouth. The ongoing concern, though, was his eyes. He had no eyelids to protect his corneas. Doctors fashioned a cone of skin where his eyelids once were — it looked like a lizard’s eye. That offered some protection, though Hardison still couldn’t blink. At night, he pressed his eyes shut with his fingers. Not that he slept much. It was better not to. He had nightmares that he was back in the fire.

Life for Chrissi, once a stay-at-home mom, was difficult, too. “You left for work one day the person I married and came home a stranger,” she told him. “It’s almost like I have to treat you as if you died.” Money troubles increased the stress. Hardison received Workers’ Comp, but the amount was based on his earnings as a firefighter — $15 per fire. He received a federal disability check for $1,200 a month, plus some funds from a private insurance policy. It was not nearly enough. The couple lost their dream home and their cars and moved in with Chrissi’s mother. “We did what we had to do to survive,” she said.

Rodebaugh

Rodebaugh was six-one with blue eyes and blond hair that he grew past his shoulders. In photos, he has a long, animated face. By all accounts, he was a talker. “He knew everything and everybody. His stories were bigger than life,” said Brian Gluck, owner of the Red Lantern, a bike shop, café, and bar on Myrtle Avenue in Brooklyn. Rodebaugh would casually mention that he’d raced cars and jumped out of a helicopter on a snowboard. Some sensed insecurity and wondered if he stretched the truth. But then the stories turned out to be true — at least, there usually seemed to be a detail or a person who lent credence to them. One thing was certain: Rodebaugh was a loyal friend. He would ride his bike three miles in the snow to help fix your car. He would stick up for you in a bar fight. Rodebaugh lost a front tooth defending Lopez once, and he never replaced the tooth. He couldn’t afford to but also seemed proud of it, evidence of his toughness. In a photo, a girlfriend with long dark hair lies next to him, her finger over the gap in his smile. Women were drawn to Rodebaugh. “He had a brute macho,” said Lopez. “He always had beautiful girlfriends.”

In 2014, Rodebaugh won the Red Bull–sponsored Brooklyn Mini Drome, ten laps around a steeply banked oval loop that he helped build, which made him something of a celebrity in Brooklyn-cyclist circles. Still, he couldn’t pay rent. For a year, he lived in a van — a VW Vanagon with a pop-up roof that served as transport to bike races as far away as Texas, though most of the time he parked it outside the East River Bar, a favorite of the Lock Foot Posi. Once, he found the van booted and managed to disassemble the lock on the wheel, but another time the van was towed. Rodebaugh had accumulated so many tickets that it wasn’t worth paying to get the van back. He couch-surfed for a while. “I get your stress, bro,” Lopez told him. “You got no chill” — no place to repair to and unwind.

And then, as often happened, Rodebaugh landed on his feet. In June 2015, he found a job as a bike mechanic—he was “a good wrench,” as mechanics say — at the Red Lantern. Gluck remembered the day he hired him. Rodebaugh drove his BMX bike into the shop and didn’t dismount. “He was sweating like hell and wasn’t wearing a shirt,” said Gluck. Rodebaugh said nonchalantly, “I hear you need a mechanic,” and reeled off the names of bike shops where he’d worked. Later, Gluck wondered why he’d worked at so many places, but he did need a mechanic — the peak season was starting. Gluck hired him for $15 an hour, enough to pay rent for a while.

Hardison

Hardison said that his life had “skidded to a halt” the day of the accident, but that was a conclusion he drew years later. At the time, he charged ahead, refusing to admit he was disabled. “Just different,” he insisted. “From here down, I was good to go,” he said, holding his hand at chin level. He and Chrissi had two more kids, two boys, one born in 2003, the other in 2004. They were unplanned but welcome. “They were his saving grace,” Chrissi said. “He had people who knew him only as he was and loved him unconditionally anyway.” The boys giggled when he snapped off a prosthetic ear, held it in the air, and said, “I can’t ear you.” They asked their friends, “Can your daddy do that?”

In 2003, Hardison returned to the tire business, opening a new shop with a partner. Even with his injured face, business was great for a while, recalled Travis McDonald, a friend and employee. Flush again, Hardison built a 7,000-square-foot house on two lots in Bartlett Woods, a tony development in Senatobia. He hoped to sell it but in the meantime moved in his family. “It was more space than we could ever use,” said Chrissi, but it was a relief after living on top of one another at her mother’s. His friends were duly impressed, though some worried that he was overreaching. Chrissi understood. “He was trying to prove that no matter what happened, he could still take care of his family,” she explained.

To outsiders, Hardison’s life seemed to be on track once again. But close friends saw a dark side. He underwent an average of seven operations a year. That kept him away from the shop for long periods, and it kept him in pain. “How could you not be addicted to pain pills?” said his boyhood friend and fellow firefighter Jimmie Neal. “He felt he needed those medications to survive.” Oxycodone became so normal, said McDonald, “he almost didn’t know he was high.” But others did. “My medicine problem,” as Hardison later referred to it, affected his judgment. “He quit running his business the way it should have been run,” said McDonald. “Things that were important weren’t important anymore. Like paying his bills.” When the prescriptions ran out, he found other ways to procure the painkillers. He later was arrested for forging a prescription and bouncing a check.

For a second time, Hardison’s life tumbled down around him. In 2007, he declared bankruptcy and lost the house. “I kept trying not to fail, but I couldn’t beat it,” he said. “I felt like a failure.”

The next year, he and Chrissi divorced after ten years of marriage. “It had been such a long road,” she said. “I felt guilty, but we were in a very destructive place. We weren’t beneficial to each other emotionally. Pat had some things he had to go through. And there was nothing that anyone could do to help him.”

Hardison had joint custody of the kids, but when they left his apartment for school, he had nothing to do. “People don’t understand how hard it is just to face the day. And it doesn’t end. It’s every day,” he said. The worst development was that, with no eyelids, his vision began to decline. He had to stop driving. “I was a 40-year-old man waiting for my mother to drive me around,” he said. “I lost everything. I was so young.”

When he met Rodriguez in 2012, the surgeon told him he could treat Hardison’s most pressing medical problem by performing an eyelid transplant. But Rodriguez also proposed a bolder solution: an entirely new face, scalp, ears, nose, lips, everything he’d lost in the fire. “We’re going to make you normal,” Rodriguez promised.

But first Hardison would have to make it through NYU’s elaborate review process, which meant he would have to deal with his painkiller addiction. Rodriguez extracted a promise. Hardison couldn’t seek narcotics from any physician but Rodriguez’s team. If he did, he wouldn’t get the surgery.

Rodriguez warned Hardison that the surgery had only a 50 percent chance of success. This would be the most extensive face transplant yet performed — including the entire scalp, ears, and eyelids. “You have to remove the old face to the bare bones,” he explained. “You have to understand: If it were to fail, there is no bailout option. You would likely die. This is a procedure that is all or none.”

Hardison’s kids were scared. “They didn’t understand why he’d take the chance,” explained Chrissi. “They loved him as he was. To them, he was normal.” The younger son had a nightmare that surgeons turned his father into a monster. But Hardison had already reached the point of all or none. “Kids ran screaming and crying when they saw me,” he said. “There are things worse than dying.”

Rodebaugh

On Wednesday, July 22, of this year, Rodebaugh was supposed to meet Saskia, his most recent girlfriend. She was 30 years old, with delicate features and braided blonde hair that fell almost to her knees. They’d met at a bicycle accident to which they were both witnesses. “I ride every day,” Saskia told me. “I feel weird walking.” One rainy day, they biked to the Rockaways together. “It was very romantic,” Saskia recalled. She liked Rodebaugh, but she told him she’d recently left an intense relationship and didn’t want another. Then, she flipped over the handlebars of a bike — one Rodebaugh had lent her — and broke her arm in four places. Rodebaugh became her nurse. “He spent days sitting with me in the hospital. I was really pissed off and angry. He didn’t flinch. He’d come in mornings to help me shower and dress and braid my hair — and no one ever touches my hair.”

That July night, Saskia texted him the address where she was having dinner with friends. He was to join her, which she hoped would cheer him up. Two days earlier, Rodebaugh had been fired from the Red Lantern. He didn’t show up for work sometimes. “You’re a great mechanic but a shitty employee,” Gluck told him. Rodebaugh didn’t disagree. That evening was his last shift with another mechanic who’d become a friend. They worked till 9 p.m., stayed for a few drinks.

Rodebaugh headed out on his road bike near midnight. He went east on Myrtle and then turned south to DeKalb. He took the bike path, though in the wrong direction and at a high rate of speed, which is how he always rode. He bicycled toward his apartment, perhaps to clean up before meeting Saskia. Near Franklin Avenue, his friends say, a pedestrian walked out from between cars. Rodebaugh hit him and was thrown from the bike. He landed on his head. He wasn’t wearing a helmet.

At Kings County Hospital, doctors wheeled Rodebaugh into surgery, where they opened his skull, hoping to release the pressure on his brain caused by bleeding in his head. Saskia didn’t learn why Rodebaugh had stood her up until two days later. When she heard, she rushed to the hospital and didn’t leave. A week after the accident, Rodebaugh emerged from his medically induced coma. He couldn’t talk because of the tubes in his throat, but he could write. “I love this girl,” he wrote to a nurse. It was the first time he’d said that to Saskia. “I’m not going anywhere,” she said, “for as long as you want me.” She slept with her head on the rail, holding his hand.

Three days after waking up, Rodebaugh became agitated. There was another bleed inside his head. Surgeons removed part of his cerebellum, hoping to reduce swelling. He fell into another coma, this one not induced. “Even if he survived, he wouldn’t have much motor control,” Saskia said later. “It would’ve been torture for him to be in a body like that.” She whispered to him that it was okay to die. On August 12, he was declared brain-dead.

Rodebaugh

That afternoon a representative of LiveOn NY, which matches organ donors with hopeful recipients, phoned Rodriguez to inform him of a potential face. He didn’t know if the donor would prove an acceptable match; genes and blood had to be tested. But he called Hardison — “I have a good feeling about this one” — and instructed him to get on the first plane the next morning.

Hardison had been summoned to New York before. Once, a Hispanic man had a face for him. The hair was dark, the skin a deep tan. Rodriguez, a Cuban-American, was against giving him a face with a different ethnicity, but Hardison didn’t care. At the last minute, the donor’s family withdrew consent. Next he was offered the face of a woman; floating testosterone would produce a beard on her face. But this, Hardison couldn’t take. Now, finally, the results on the latest candidate were in: Rodebaugh was a match.

Two days after he was declared brain-dead, at 7:30 a.m. on August 14, the surgery began. Rodriguez started on Rodebaugh, carefully dissecting the half-inch-thick scalp away from the skull. He worked from the back toward the ears, then the nose, which he sawed off. The trick was to cut away the tissue while preserving nerves, muscles, and the carotid arteries and the internal jugular veins—the “big pipes.” The most delicate task was the eyelids. Rodriguez had endlessly practiced this part of the operation in his mind. He worked from inside, cutting the white stringy muscles from the bony sockets. It took twelve hours to completely remove Rodebaugh’s face.

In a second operating room, another surgical team had been removing Hardison’s face, depositing it in bags marked medical waste. “Now there is no semblance of normal,” said Rodriguez. “We’re looking at raw features.” The only hint of a human was the blue of Hardison’s irises. This thing has to work, Rodriguez told himself.

Rodriguez laid Rodebaugh’s face over Hardison’s head. He “snap fit” the tips of the cheekbones and chin, and the nose with screws and metal plates, securing the face in position. He attached two whitish cables of sensory nerves to Hardison’s lips, which perform the face’s most complicated movements. Other nerves would regenerate, creating pathways to the new face. Eventually, hopefully, Hardison would have sensation. Scar tissue would bind pinkish strands of muscles to the remnant muscles of Rodebaugh’s face and eventually power his smile, his cheeks, the wrinkling of his forehead.

All was going according to plan until Rodriguez attempted to sew Rodebaugh’s internal jugular vein to Hardison’s. There was a size mismatch: Hardison’s jugular was bigger. A suture failed and Hardison lost a couple pints of blood in a couple minutes. Rodriguez clamped the external carotid, stopping blood flow to the entire face, and changed his approach. Instead of joining the jugulars end to end, he cut a hole in the side of one, allowing him to control the size of the opening, and sewed the other to it. After 30 minutes, he unclamped the carotid and let blood flow through the face. The pale cheeks turned pink. He pricked Hardison’s lips with a pin. They bled, a relief.

It was Hardison’s face now, though it seemed to have a will of its own. The face started to swell. It was expected, but still striking. In a few minutes, the face was 50 percent larger than it had been. “It looked like a boxer’s face at the end of 15 rounds,” said Rodriguez.

Twenty-six hours after it started, the operation was over. Technically, the surgery was a triumph. Still, Rodriguez didn’t yet know if the transplant would take. “I’m 100 percent convinced it will work. It has to work. But you never know if it’s going to work.” Three days later, the swelling had diminished a bit. “I can see some movement of his eyelids,” Rodriguez recalled. It was the sign he was waiting for.

See and hear Patrick Hardison speak. Video by Greg Jeske and Chris Wade.

Hardison

When I visited Hardison in the hospital two months after the operation, what was most startling about his appearance was his youth. His burned face had been scarred and hairless, his nose a stub; he looked 70. With his new face, he appeared to be in his mid-20s, Rodebaugh’s age, and, coincidentally, Hardison’s age at the time of his injury. The face was still swollen and round, and without expression since he couldn’t yet move his mouth or cheeks. It was impossible to read his mood. To me, he looked vaguely unhappy. He drummed his fingers and tapped his ear, which wasn’t quite working yet. His tongue still wasn’t moving much — the dissection of blood vessels in his neck had impaired its function — and his voice was garbled, seeming to come from deep inside him, as if he were performing an act of ventriloquism. Hardison was impatient. Would he be able to talk again? Rodriguez assured him his progress was ahead of schedule. “Smile,” he said, and Hardison mustered the hint of a smile. Rodriguez hoped for more. “Smile,” he repeated. “I did,” said Hardison.

Hardison will be on immunosuppressant drugs for the rest of his life. Even with that precaution, Rodriguez said, “there will be a rejection — not if but when.” Rodriguez estimates that between three and five of the now 30 patients who have received facial transplants have died after rejection. When it happens to Hardison, doctors will treat it with massive amounts of immunosuppressants and steroids and hope for the best. In the meantime, Hardison still has considerable pain through his cheeks and forehead and always will. Doctors carefully titrate his Oxycodone, concerned about his past addiction. “I can live with the pain,” Hardison assured me.

The next step in Hardison’s recovery was to reintroduce himself to his five kids, his mother, sister, brother, and Chrissi. It was the kids he worried about most. Nine weeks after the operation, on October 8, they walked tentatively into his hospital room. Hardison bounded toward them with a surprisingly quick step. His face was slowly healing, but the rest of him was fit, almost athletic. Hardison hugged each one fiercely, grabbed tissues to wipe the tears that seeped out from under his new eyelids.

The youngest especially, the 10- and 11-year-old boys, put on brave faces. “No matter how big of a medical miracle it may be, that doesn’t make it comfortable for his kids,” said Chrissi. “It’s still having to adjust to someone else’s face on his body.” After all, a face is more than a face. It’s an identity, a signal to the world of who a person is. By four months of age, infants’ brains recognize faces at nearly an adult level—especially the faces that belong to their parents. The younger boys touched his hair, now a half-inch long. One of the boys joked that he’d buy his dad earrings for his pierced ears. “Hell, no,” said Hardison. It was reassuring to hear his response, so typical of their dad. Still, they wanted to recognize him, to know him. “When I see his face, I want to memorize it, so the next time I see him, I know it’s my dad,” said one son.

Hardison had long ago abstracted his sense of who he was from how he looked. The burn face had been a mask too. For him, this mask was better. One day, he walked to Macy’s a few blocks from the hospital, and no one stared and no one pointed, he told Rodriguez in tears.

Rodebaugh’s mother said she wanted to see her son’s face on its new body, as if perhaps she might get one more glimpse of her son. But her son’s face was long gone. I showed Saskia a photo of Hardison, and she couldn’t recognize the face of the man who had loved her. The face had taken the shape of Hardison’s bone structure. Hardison wasn’t interested in talking about Rodebaugh. Not yet. As far as he was concerned, the face belonged to him, as if he’d been born with it. It had his hair color and skin tone. “It’s mine,” he said.

*This article appears in the November 16, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.