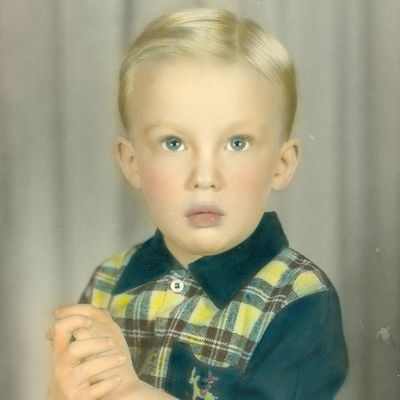

Left: Donald Trump as a toddler in Queens. Right: Brothers Larry and Bernie Sanders in Brooklyn, c. 1944.

Photo: Facebook (Trump), Courtesy of Larry Sanders (Sanders)

Things you buy through our links may earn Vox Media a commission.

THE FEED

alejandro mayorkas

The Mayorkas Impeachment Trial Was a Joke

early and often

The ‘Uniparty’ Delusion Shared by MTG and RFK Jr.

fog of war

GOP Senate Candidate Has a Mystery Bullet in His Arm

tremendous content

Trump Is Still Fuming Over Kimmel Mocking Him at the Oscars

sports betting

The NBA Is Facing a Blockbuster Gambling Scandal

politics

Bob Menendez’s Possible Legal Defense: My Wife Did It!

games

The NBA Playoffs Are Going to Be So Much Fun

trump on trial

What Happened in the Trump Trial Today: 7 Down, 11 to Go

the national interest

Conservatives Suddenly Realize Tucker Carlson Is a Lying Russia Dupe

daddy issues

Why Is Elon Musk Dragging His 3-Year-Old Around the World?

trump on trial

The Who’s Who of Trump’s Trial

early and often

Murder Rates Are Dropping Despite GOP ‘Crime Wave’ Rhetoric

early and often

Johnson’s Foreign-Aid Plan Relies on Democrats Saving Him Repeatedly

early and often

The House’s Anti-Mike Johnson Club Gets a Loud New Member

early and often

Did Trump Really Consider Making RFK Jr. His VP Pick?

trump on trial

‘Sleepy Don’: Trump Falls Asleep (Again!) During Hush-Money Trial

the money game

Elon Musk Has Forgotten What Tesla Is

the national interest

Paul Krugman Is Right About the Economy, and the Polls Are Wrong

early and often

The Never Trumper Listening to Trump Voters

tremendous content

Trump’s Gettysburg Address Featured a Pirate Impression

the national interest

Marjorie Taylor Greene Attempts Trump Legal Defense, Fails Very Badly

encounter

The Woman Who Ate Eric Adams for Breakfast

encounter

Salman Rushdie Parties Again

the money game

Trump Media’s Stock Price Is Plummeting. His Election Odds Aren’t.

trump on trial

Free the Trump Trial Transcripts